Extra Information

Warning

The diseases described on the following pages contain images and film material taken during operations. Decide for yourself if you want to see these images. Please also note our imprint and the legal information. The Baermed practice assumes no liability. Do you really want to see the page!

Bile

Topics

1. a coherent system

Gall bladder – bile ducts – bile duct outlet

Gallbladder – bile ducts – bile duct outlet: a coherent system. The gallbladder is located at the lower border of the liver as a reservoir of bile. The associated bile duct system begins in the liver, where liver cells produce bile and release it into tiny bile ducts that then traverse the liver.

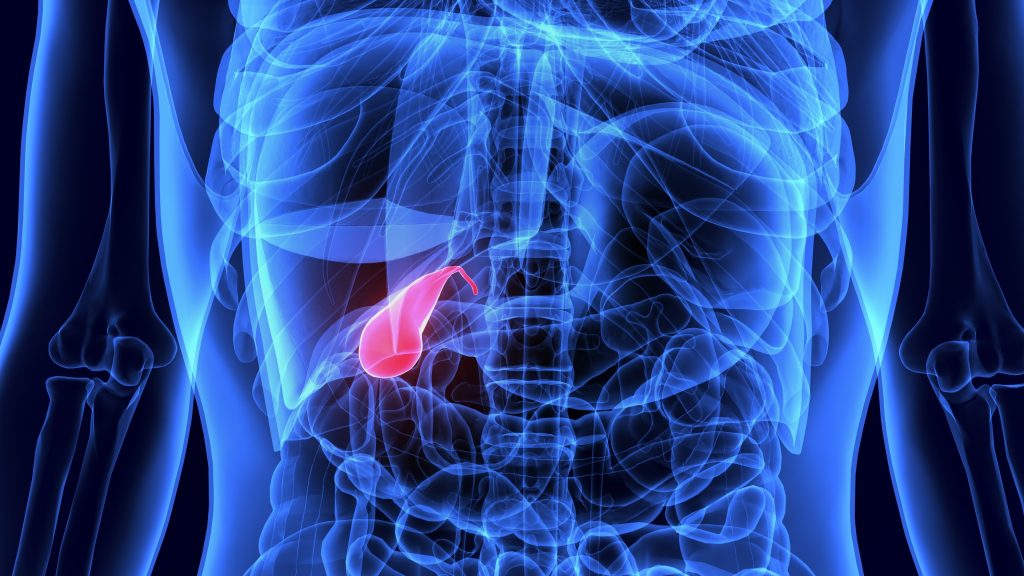

Where is the gallbladder located?

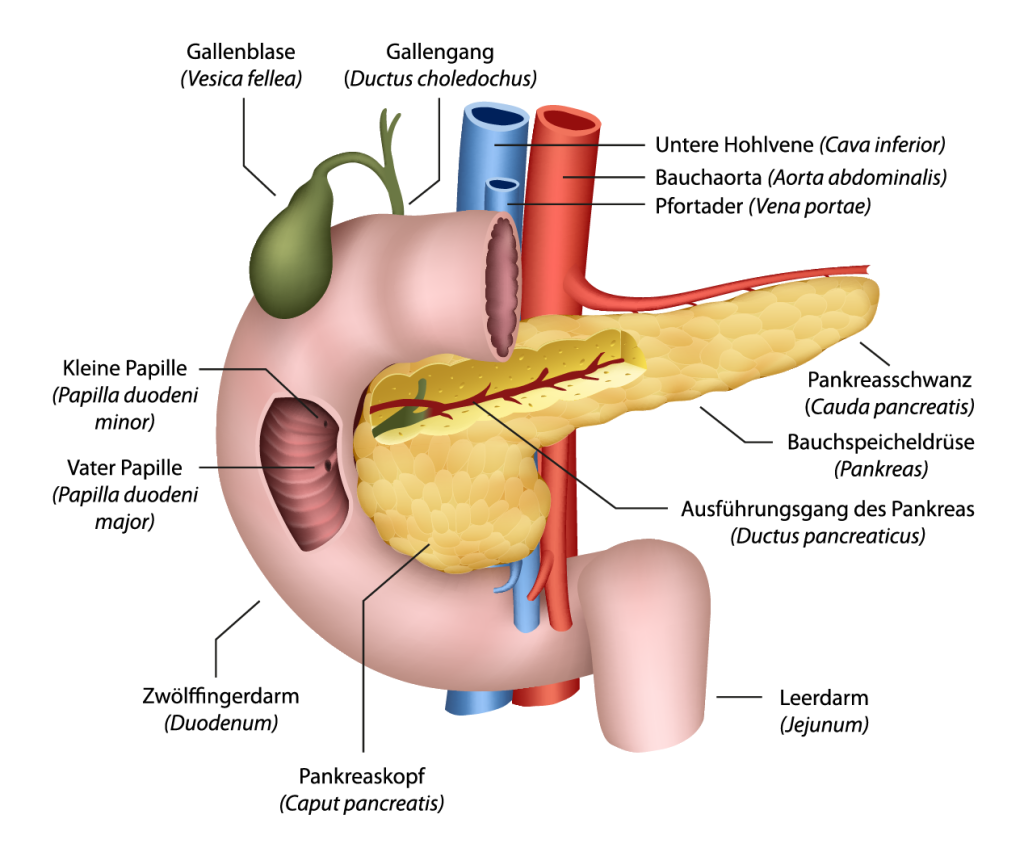

The gallbladder (lat. Vesica fellea) is an oval hollow organ about three to four centimeters wide and five to ten centimeters long; it is located at the lower edge of the liver (Fig. 1). The associated bile duct system (Fig. 2) begins in the liver, where liver cells produce and release bile into minute bile ducts that traverse the liver. These small bile ducts subsequently open into two larger ducts at the lower edge of the liver and then leave the liver. Both join after a short distance to form the common bile duct, which at one point connects to the gallbladder.

Further on, the common bile duct passes over the head of the pancreas to the duodenum. At this point, together with the pancreatic duct, it enters the intestine. At this transition into the intestine, the so-called papilla is located as the closure of the bile duct system, which can control the flow of bile.

In the gallbladder wall are muscle cells that involuntarily contract or relax the gallbladder With this special mechanism, the gallbladder can absorb bile when it becomes flaccid and later expel it through contractions. It serves as a reservoir for the absorption of bile. The bile ducts are also closely related to blood vessels (Fig. 3).

The liver cells produce about 800 to 1,500 milliliters of bile per day, some of which flows directly into the duodenum via the common bile duct. The remaining part of the bile is backed up into the gallbladder, where it is stored and thickened.

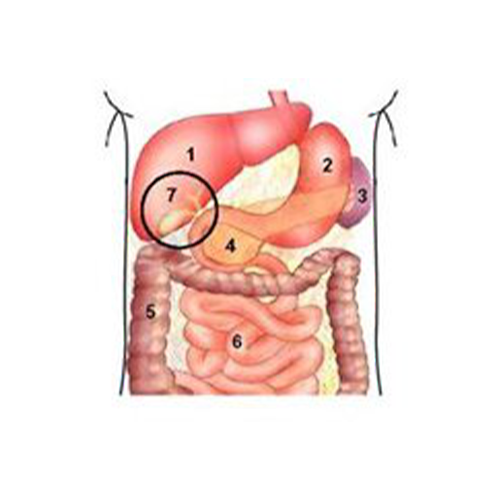

1 Liver

2 Stomach

3 Spleen

4 Pancreas

5 Large intestine

6 Small intestine

7 Gall bladder

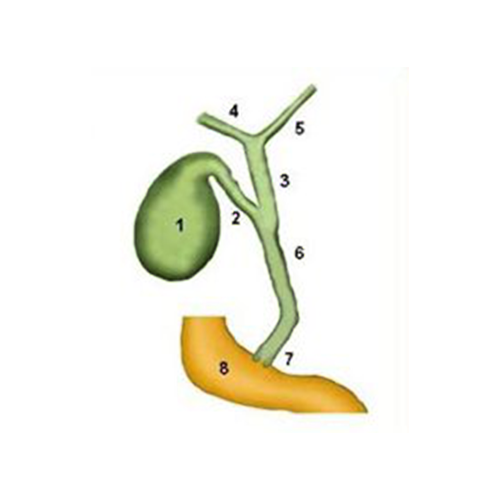

1 Gall bladder body

2 Gall bladder duct

3 Main bile duct

4 Right hepatic duct

5 Left hepatic bile duct

6 Common bile duct

7 Pailla Vateri

8 Duodenum

How does the gallbladder work?

Bile plays a central role in the digestion of fats as well as in the elimination of breakdown products from liver metabolism. It is composed of a variety of substances, of which bile acids, cholesterol, lecithin, certain fats and also some enzymes make up the main components.

The need for bile is dependent on nutrition. Only a small amount of bile is needed in the small intestine between meals, so most of it is stored in the gallbladder. During the passage of food through the stomach into the initial part of the duodenum, a variety of digestive mechanisms are activated via the control of autonomic nerves and messenger substances (hormones). In addition to the production of gastric juice, this also includes the secretion of bile. The remaining part of the bile is backed up into the gallbladder, where it is stored and thickened.

Since the liver cannot immediately increase bile production at will, reserves are mobilized from the gallbladder. Digestive hormones from the stomach and nerve impulses from the autonomic nervous system cause the gallbladder to contract and empty its bile juice reserves via the common bile duct into the duodenum and thus into the small intestine.

In this way, sufficient bile is available to digest the fats ingested with food in the small intestine and ultimately to absorb them into the body.

2. gallbladder and bile duct system

Diseases, symptoms, treatment and surgery of gallstones

Gall bladder and bile duct system

The gallbladder, as a reservoir of bile, is located at the lower border of the liver. The associated bile duct system begins in the liver, where liver cells produce bile and release it into tiny bile ducts that then traverse the liver.

The gallbladder, as a reservoir of bile, is located at the lower border of the liver. The associated bile duct system begins in the liver, where liver cells produce bile and release it into tiny bile ducts that then traverse the liver. Read more >

These eventually collect at the inferior border of the liver in two larger ducts and exit the liver. Both unite after a short distance to form the common bile duct, which at one point gives off the connection to the gallbladder. Further on, the common bile duct passes over the head of the pancreas to the duodenum.

There, together with the pancreatic duct, it enters the intestine. At this transition into the intestine, the papilla of Vater (lat. papilla vateri), a critical bottleneck of the biliary system, is located as the closure of the bile duct system. In front of this bottleneck, smallest stones can often remain. From the close spatial relationship of the two outlets at the bile duct and the pancreas, it is understandable that certain diseases of the bile ducts can lead to pancreatitis.

How does the bile duct system work?

Bile, which serves to digest fats in the duodenum and small intestine, is composed of a variety of substances and is also the transport medium for the liver’s breakdown products. Since the demand for bile is food-dependent and the liver cannot immediately increase its bile production, bile is always stored in the gallbladder to be immediately squeezed into the duodenum when food is consumed. During the passage of food through the stomach into the duodenum, a wide variety of digestive mechanisms are activated. Read more >

In addition to the production of gastric juice, this also includes the secretion of bile from the gallbladder. This process is controlled by a highly complex system of nerve impulses and messenger substances that, among other things, cause the gallbladder to contract and empty its contents into the duodenum via the common bile duct.

Stone impaction and acute inflammation of the bile ducts

Unfortunately, a regulatory system as complicated as that of bile production, bile storage and bile distribution is also prone to failure. If there is a change in the composition of bile or delayed emptying of the entire system, one of the most common diseases in this area develops: the formation of gallstones. Read more >

Fortunately, most of the stones, which are often quite large, are located in the gallbladder, where they can remain for years without ever becoming noticeable. However, in about 20% of all stone carriers, gallstones are also found in the bile ducts. There, the small stones that “migrate” from the gallbladder into the narrow common bile duct and become trapped or, if they are small enough, leave the bile duct via the duodenum are most noticeable.

Inflammation of the bile ducts can occur when there is a slow flow of bile in the system over a long period of time, giving bacteria from the duodenum an opportunity to move backward into the common bile duct and infect the bile. Finally, two rather rare diseases of the bile ducts should be mentioned: The malignant tumors and the diseases that can cause delayed bile flow due to inflammation in the ducts.

The highly rare malignant bile duct tumors of the common bile ducts occur in three different “floors” outside the liver: Where the two main bile ducts leave the liver at the lower edge of the liver, up to the point where the two bile ducts just unite (hepatic fork), in the area of the middle third of the main bile duct, and at the final stretch of the main bile duct that extends from the upper edge of the pancreas to the duodenum.

Inflammation can cause the bile ducts to become narrowed. These inflammatory constrictions are the result of infections of the gallbladder and pancreas (with or without stone disease) or the result of previous surgery in this area, which damage the bile ducts in the blood flow or directly and can therefore lead to a stricture (narrowing).

Symptoms of bile duct disease

Many patients with gallstones and bile duct stones do not experience any symptoms for the rest of their lives, and the important laboratory values are also inconspicuous. Others may experience mild discomfort or minor tenderness in the upper abdomen, or complain of intolerance to fatty and flatulent foods. However, if the disease causes stones to pass from the gallbladder into the ductal system, the patient suffers severe, collic-like pain in the right upper abdomen that lasts from a few minutes to a few hours and can sometimes radiate to the right shoulder and back. Read more >

If this causes bile to back up into the liver, a yellow discoloration of the eyes and skin as well as brown urine and discolored stool may occur. If the patient is feverish, has chills and feels seriously ill, it must also be assumed that there is inflammation of the bile ducts, which can sometimes extend to the pancreas.

A doctor should be consulted already in case of a permanent intolerance of food, in case of accompanying nausea, but at the latest in case of the occurrence of collic-like complaints in the upper abdomen, in order to clarify whether the cause is gallstones or another disease of organs of the right upper abdomen.

Diagnosis and Necessary Clarifications for Bile Duct Stones

First, the doctor will start with a thorough questioning of the patient: Has the patient been avoiding certain foods (fats, coffee, chocolate) for a long time? Is he taking any specific medications? What was the pain like and in which direction did it radiate? Was there yellowing of the eyes and skin? Have the stools ever been discolored, the urine dark? Have there been any episodes of fever or chills? Read more >

This is followed by a comprehensive physical examination including the abdomen. Afterwards, a blood sample is taken to check the inflammatory signs and liver values. In doing so, one pays particular attention to those values that can signal a bile stasis.

One of the most important examinations is ultrasound examination of the upper abdomen. In most cases, it provides basic information about possible gallstones and bile duct stones, bile stasis (dilated bile ducts), and signs of inflammation.

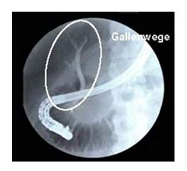

Nevertheless, the examiner may not be able to see the smallest stones on ultrasound if the bile ducts are severely dilated, but the patient still has typical “stone complaints.” In this case, one will usually perform a CT scan and possibly bile duct imaging (ERCP). The latter involves X-ray contrast imaging of the bile ducts using duodenal endoscopy, and stone removal can also be performed in the same session.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as a further diagnostic option is reserved for special questions. Unfortunately, even today, despite many highly specialized procedures, there is still no procedure that can 100% prove the presence of gallstones. Therefore, the exact sequence of diagnostics for bile duct stones always requires a synopsis of all examination results and laboratory values, and it takes into account the patient’s symptoms and age. This is the only way to find an individualized and low-complication therapy for the rehabilitation of the bile ducts.

Treatment and surgery of the bile ducts

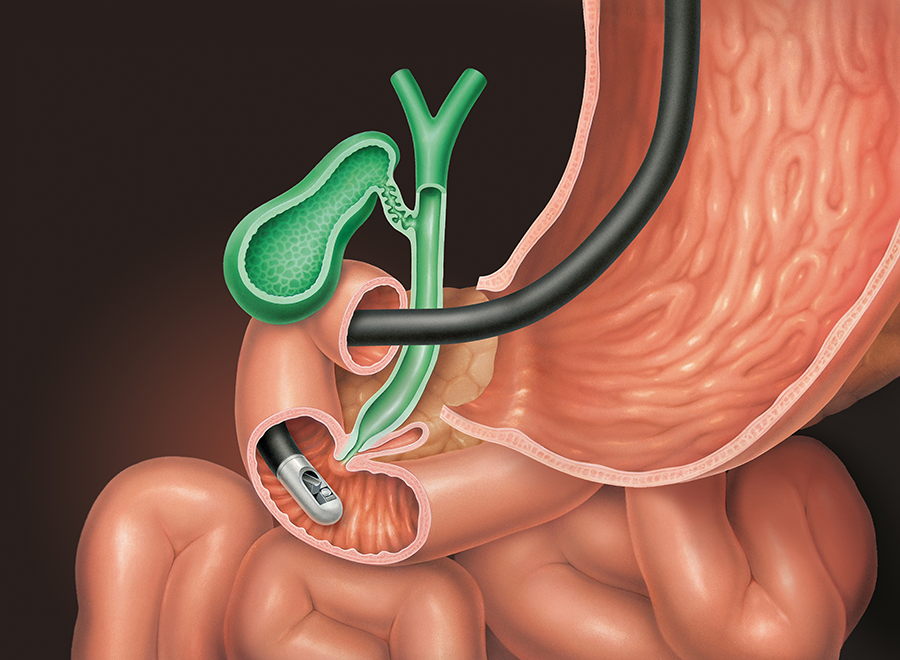

Removal of the smallest bile duct stones benefits significantly from the era of endoscopy. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and endoscopic papillotomy (EPT) in 1974 opened up completely new, non-surgical options for the diagnosis and treatment of biliary tract disease. How do these procedures work? Read more >

If a patient presents with colicky symptoms, perhaps already with yellowing of the skin, it is necessary to remove the bile duct stones and restore normal bile flow. For this purpose, the patient is given a sedative before the examination and is then placed on a couch. The throat is thoroughly anesthetized with a spray, as in a gastroscopy.

The examining specialist also inserts a thin tube, the end of which has an optic, through the patient’s mouth and advances it into the duodenum. At the point where the common bile duct enters the intestine, also called the papilla, the common bile duct is visited and initially imaged with contrast medium to show and assess local findings. The examiner then decides on a specific sequence of therapy, which can be performed immediately via the endoscope. Two examples:

The papilla is too narrow to allow good bile drainage and to allow small stones to pass. Therefore, it is dilated with a special knife or expanded with a small balloon. There are stones in the common bile duct. They are removed from the bile duct with the help of a small basket. Inflammation of the bile ducts, with or without stone disease, is also treated with incision dilation of the papilla, and the bile ducts are flushed.

Intravenous administration of antibiotics is a matter of course. Now 95% of all patients can be cleared of their bile duct stones using this procedure, and fortunately, complications of ERCP and EPT are rare. At most, there may be bleeding from the interface of the papilla, or inflammation of the pancreas. If the patient still has his gallbladder, it is removed by minimally invasive surgery after the bile duct stones have been removed and all liver values and clinical findings have normalized.

What happens after the treatment?

As soon as the patient is fully awake after the procedure, he or she is allowed to stand up. He is also allowed to drink and eat light food again that day. Only antibiotic treatment due to the risk of acute inflammation must be continued for a few days. Liver value checks and observation of skin color are used to determine whether the bile stasis is decreasing and whether the therapy was successful.

What must be paid attention to in the future everyday life?

The procedure is well tolerated and the disease usually heals without consequences. It is very rare for stones to reappear in the common bile duct after gallbladder removal and bile duct repair.

Historical

Since ancient times, bile has been known as a bodily fluid. It was a component of the ancient four-juice doctrine, which reflected the concept of disease causation at that time.

Until then, scientists and doctors believed that man and matter were made of one element. In the ancient four-fluid theory, however, the physician Empedocles of Akragas also assigned four bodily fluids to the basic substances he determined: air, water, fire and earth: blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. It was believed that an imbalance in the mixture of these humors would cause disease, but also determine characters. Read more >

Thus, yellow bile belonged to fire and circumscribed the character of the choleric who exclaims, “My bile is running over!” Today, it is known that the development of gallstones is actually associated with an altered composition of the bile. Many accounts show that people have been plagued by gallstone disease for centuries, but there have been only non-surgical therapies to relieve their symptoms.

Wound physicians intervened only when gallstone-containing abscesses broke through to the outside. When the prerequisites for abdominal surgery were met with antisepsis and general anesthesia in the 19th century, there was a rapid increase in knowledge in the field of surgical therapy of gallbladder and bile duct stones as well as new diagnostic procedures, in that the aim was to visualize the biliary system via contrast medium administration in order to localize stones there.

In 1882, Karl Langenbuch succeeded in performing the first gallbladder removal, and in 1890, Ludwig Courvoisier became the first surgeon to dare to open the common bile duct to remove a stone and restore bile flow. The particular difficulty was to create a suture-tight closure of the bile duct. Many surgeons at that time discouraged surgical therapy of the biliary tract, knowing that a “bile leak” of the duct resulted in serious complications.

The saving idea to grant bile drainage came from Hans Kehr in 1895, who invented the T-drainage, which is still used today. This is a very thin plastic tube that is inserted into the common bile duct and passes through the abdominal wall, allowing bile to drain freely. Once wound healing in the bile duct area is complete, the drain can be removed without complications.

In the following decades, there were still various surgical and diagnostic improvements, but the basic surgical therapy hardly changed. The development of the ERCP examination (ERCP stands for Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreaticography) by Ludwig Demling in 1974, a special X-ray contrast imaging of the bile ducts that simultaneously offered therapeutic possibilities, was groundbreaking.

Last but not least, the development of minimally invasive surgery (keyhole surgery) since 1985 revolutionized surgical procedures in the area of the gallbladder and bile ducts and arguably offers patients a much more comfortable surgical therapy.

3. inflammation of the gallbladder due to gallstones

Symptoms, treatment and laproscopic surgery

Gallbladder diseases and surgery

The most common diseases of the gallbladder and ducts are caused by gallstones. The formation of gallstones is a highly complex process that can be triggered by various causes. If the composition of the bile juice is altered and the emptying function of the gallbladder is disturbed, stones can form in the gallbladder due to “thickening” of the bile. Read more >

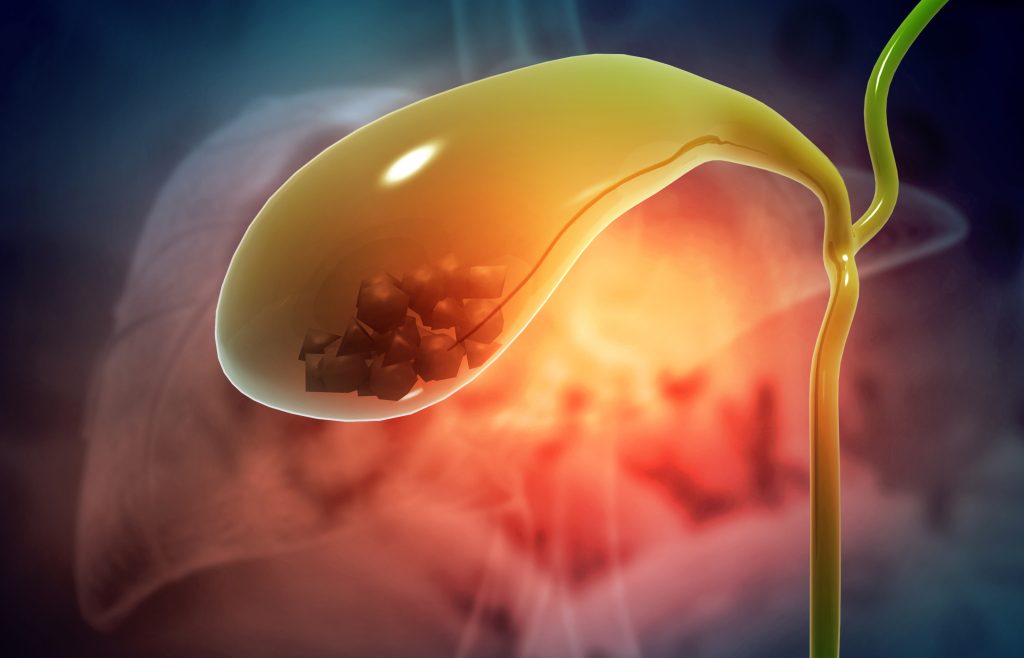

Gallstones vary widely in size, shape, and composition (Fig. 4). Cholesterol stones (80%) are most commonly found in the gallbladder and bile duct and often originate in the gallbladder and are light in color. Pigment stones (bilirubin stones) tend to be dark and are found in only about 20% of cases. Finally, there are also the so-called mixed stones, which are relatively common in any composition and in different shapes and colors.

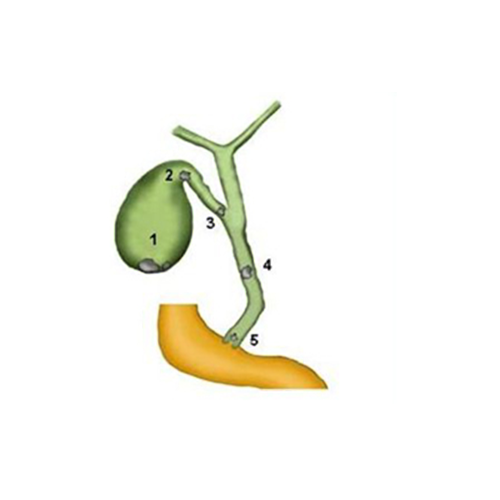

Gallstones can linger in the gallbladder for years without causing any symptoms. They are therefore often called “silent gallstones”. The dangerous stones are the small ones, as they can enter the bile ducts and obstruct bile flow in the papilla area, for example.

The typical symptoms of gallbladder colic are due to a discharge of such a small stone. If a stone passes the narrow points (Fig. 5), colic results, but if it remains stuck at a narrow point in the common bile duct, the bile can no longer flow away and backs up into the liver. This backwater leads to a yellow discoloration of the eyes and skin. The urine becomes dark and the stool light in color because the bile pigments can no longer fully enter the duodenum.

Small, but also larger stones, which cannot leave the gallbladder, lead to irritation of the gallbladder mucosa and consequently to inflammation. This can occur quite acutely or be chronic. Such a process can take weeks and months, often years.

Fig. 4: Opened gallbladder with gallstones

Fig. 5: Gallstones and their localization

1 Stones inside the gallbladder

2 stones at the gallbladder outlet

3 Stone at the junction with the common bile duct

4 Stone in common bile duct

5 Stone in the papilla

Symptoms of gallstones

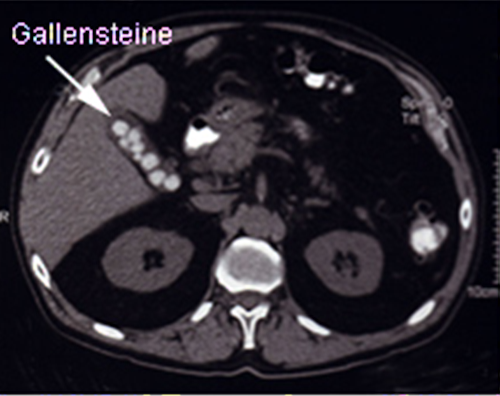

The first indications of gallstones may be quite nonspecific. Upper abdominal symptoms, such as malaise, bloating or mild digestive problems after high-fat and large meals, may have been present for a long time. Often gallstones are even not noticed at all. They are only detected “by chance” during a routine ultrasound examination (Fig. 6). Read more >

The typical symptoms of biliary colic are cramping, burning or probing pain in the right and middle upper abdomen that can last from a few minutes to several hours. Pain radiation to the right shoulder and/or back can often be observed. Colic may also be accompanied by nausea and transient yellowing of the skin. Some patients also have diarrhea. However, it is important to note that all of these signs can occur with other conditions and are not specific to gallstone colic.

In the case of cholecystitis, the patient suffers from fever, in the acute episode up to 38 or 39°C, sometimes also from chills. In general, patients feel unwell and suffer from loss of appetite. Thanks to their experience with these colics, many know precisely after which foods they occur and often avoid them for years. Fatty foods are well known, such as cheese, fried eggs or fried food.

Gall bladder disease diagnosis

Gallbladder stones may not cause any symptoms for a very long time. Patients often seek medical attention because of acute, colicky pain with or without fever that they can no longer control with their own pain medications. As with any disease, the doctor must first conduct a very detailed questioning.

The type and duration of pain, its characteristics and radiation, the relationship with food intake, observations during defecation, and color of urine and stool are some of these possible questions. A complete abdominal examination is necessary, and special blood tests are also performed to detect signs of inflammation, liver problems, and biliary obstruction. Read more >

One of the most important examinations today is that with ultrasound, which can be used with the greatest certainty to determine whether stones are present in the gallbladder, whether the bile ducts are obstructed, and whether the gallbladder wall is thickened as a sign of inflammation (Fig. 6).

This examination is somewhat less accurate for stones in the bile duct system. Other examination methods, such as radiographic imaging with contrast medium, CT (Fig. 7) or MRI, are only necessary for special questions.

Treatment and surgery for gallstones

Existing colic is treated with analgesics and antispasmodic medications. Patients should eat only liquid food or very light meals in this situation. Antibiotics must also be used for acute gallbladder inflammation and fever. In this combination, colic and inflammation can normally be treated well. If gallstones are detected, there is a great risk that colic will recur or that pancreatitis will develop. Therefore, surgery is generally indicated for the following gallbladder lesions: Read more >

- Gallstones detected by ultrasound with a history of colic or inflammation, after resolution of symptoms (operation “à froid”).

- Acute gallbladder inflammation that does not resolve after antibiotic administration.

- A previously experienced pancreatitis, which is due to gallstones.

- After removal of gallstones in the bile ducts by ERCP (Fig. 8).

- Among the surgical techniques available today, a basic distinction is made between the minimally invasive laparoscopic procedure and the open, conventional gallbladder removal.

Laproscopic gallbladder removal

Today, the gallbladder is usually removed using a minimally invasive method. The procedure is well known to the general public from many TV reports and is called “laparoscopic cholecystectomy” in medical language.

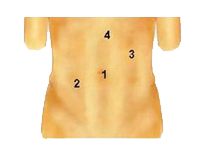

This method has the advantage that the abdominal cavity can be accessed through very small incisions (Fig. 9), resulting in fewer large wounds. Thus, the cosmetic result is clearly better, the pain after surgery is significantly less and patients are back home faster. Read more >

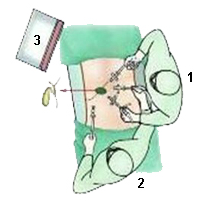

In keyhole surgery, the patient lies supine on the operating table with the legs supported on props (Fig. 10). After thoroughly disinfecting the surgical field and covering it with sterile drapes, the surgeon opens the skin to the right of the navel or in the umbilicus about one to two centimeters and then sticks a special blunt needle (Veress needle) into the abdominal cavity.

A syringe and some saline solution are then used to test whether no blood vessel has been hit and whether there is actually air in the abdomen. Carbon dioxide is now pumped into the abdominal cavity via the Veress needle. This causes the abdominal wall to lift away from the internal organs, creating a space in which to work with the instruments.

Subsequently, a sleeve is advanced into the abdominal cavity through the skin incision at the navel and a small camera with light is inserted into the abdominal cavity through this sleeve. Three more such guide sleeves are inserted into three further small skin incisions of five to ten millimeters under camera control. The working instruments, such as forceps and current hooks, can now be inserted via these additional access points.

1 For optics 10 mm (later 20mm)

2 5mm

3 10mm

4 5mm (optional)

1 Operator

2 Assistant

3 Monitor

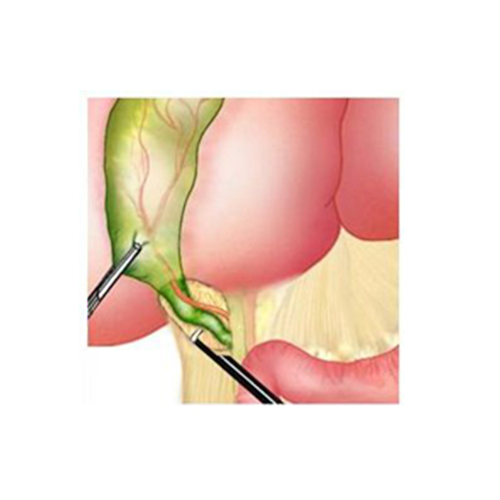

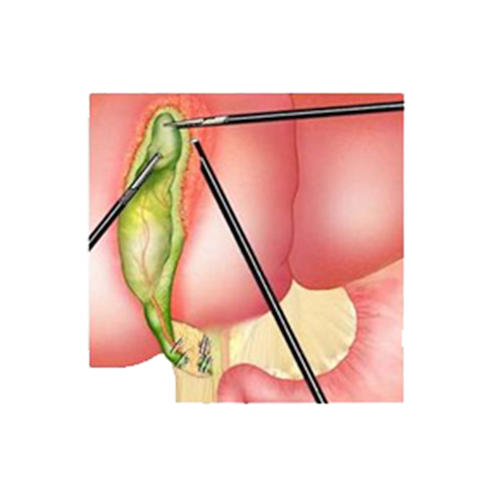

Step 1

First, the assistant carefully grasps the gallbladder at the blind end and pulls it upward. The surgeon grasps the gallbladder near the outlet of the bile duct and opens the peritoneum surrounding the gallbladder with a hook over which electricity flows. Careful dissection can reveal the gallbladder duct and gallbladder artery (Fig. 11).

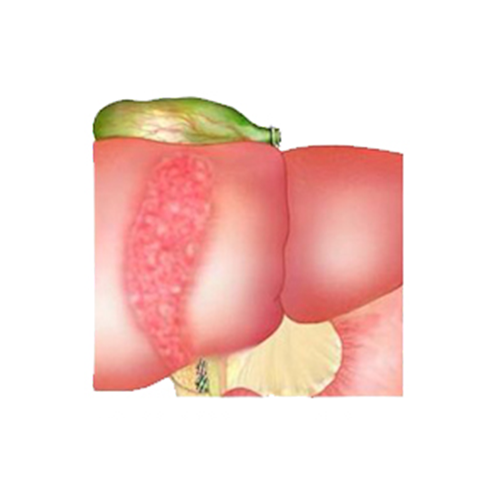

Step 2

Once these structures are clearly identified, the common bile duct and common bile artery are clamped with two metal clips (Fig. 12). These clips remain in the abdomen for the rest of the patient’s life and can later be seen again on X-rays.

Step 3

In a further step, the gallbladder is now peeled out of the liver bed with the hook electrode (Fig. 13). This often results in very small hemorrhages in the liver bed, which are scabbed over with electricity.

Step 4

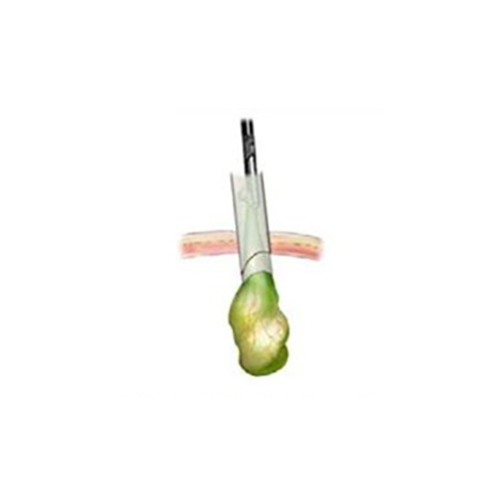

Once the gallbladder could be detached from the liver bed, it is first placed on the liver surface (Fig. 14).

To bring the gallbladder out of the abdomen, the camera must be moved to another sleeve. The sleeve at the navel is replaced by a larger one with a diameter of 20 millimeters. A grasping forceps is now inserted into this, the gallbladder is grasped at the outlet of the bile duct and pulled outward through the sleeve (Fig. 15). Read more >

The camera is used to carefully check once again that no bleeding has occurred anywhere in the liver bed. All the sleeves are then removed and the skin incisions are sutured closed with one or two stitches.

There are cases that are not suitable for a minimally invasive method or in which open surgery must be continued after a laparoscopic start. This is the case, for example, if the patient has already had previous operations in the upper abdomen with extensive adhesions.

Sometimes a gallbladder is also so strongly caked with its surroundings due to acute or chronic inflammation that laparoscopic surgery would entail too great a risk of bile duct or vascular injury due to the lack of an overview. Therefore, each patient must be informed prior to a planned laparoscopic procedure that a switch from the laparoscopic method to the open technique may be necessary.

Carefully informing the patient about the surgery and making sure that the patient really understands the information should always be considered important tasks by the surgeon in charge.

The open gallbladder surgery

The difference to the minimally invasive method is basically only in the access (Fig. 16). The rest of the technology is the same. Until a few years ago, open surgery was considered the standard method for gallbladder removal. During this procedure, an incision of about six to ten centimeters below the right costal arch is made to gain access to the abdominal cavity. Read more >

The gallbladder at the lower edge of the liver is presented with hooks, and the small artery for the gallbladder as well as the gallbladder duct are visited, pierced around and cut. Subsequently, the abdominal wall is closed again layer by layer.

Whether laparoscopic or open gallbladder surgery is an option depends on a number of factors and can only be answered on an individual basis. In principle, the laparoscopic method should be used first. If this is not possible, the open method must be chosen. After previous operations in the upper abdomen (stomach or intestinal operations), often only the open method is possible due to adhesions. However, this usually only becomes apparent during the operation.

Patients with severe cardiac conditions may need to refrain from laparoscopic surgery because the pressure in the abdomen rises due to the distending gas, carries over to the diaphragms, and can have a disabling effect on cardiac function.

Fig. 16: Ribbed bow edge cut

Special cases

In special cases, laparoscopic surgery can also be performed with very fine instruments (2mm diameter). A method using a single incision is newly introduced.

What happens after the treatment?

General anesthesia is required for both laparoscopic and open surgery. The pain after surgery is usually minor and can be treated very well with the usual painkillers. Immediately after anesthesia, the feeding tube can be removed.

On the day of the operation, patients can already drink again and they should stand up again. On the first day after surgery, light meals can be started. As a rule, patients can leave the hospital after three days. The wound sutures are removed after about eight days. Read more >

Increased physical activities can be started after one week, and the ability to work depends on the individual workload in each case.

Problems associated with gallbladder surgery are rare. Occasionally, bleeding from a vessel or leakage from the bile duct occurs when a clip is not perfectly placed. The main dangers of gallbladder surgery arise from the very different anatomical variants of bile ducts and vessels; there are innumerable such variants and many insidious courses of these structures, which demand a great deal of skill even from very experienced surgeons.

In both open and laparoscopic surgery, the common bile duct can be mistakenly injured, blocked with a clip, or partially severed – fortunately, this happens very rarely. The main risk is injury to the common bile duct, but this occurs in only 0.3 to 0.9% of cases.

What needs to be considered in the future everyday life?

After the wound has healed, the patient can resume his or her normal life. It is extremely rare for new gallstones to form in the common bile duct after gallbladder removal. Only patients of Asian descent are known to have diseases in which this is more common.

Most patients never have gallbladder problems again after gallbladder surgery. However, since the large reservoir of bile for fat digestion is now missing, these patients should generally be advised to be cautious about eating large amounts of fat in the future.

Historical

Even in ancient times, gallbladder and bile were known for a long time and played a central role, especially in the Hippocratic four-juice doctrine. It was Hippocrates of Kos, for example, who was able to give a new direction to the concept of the origin of disease at that time. He also assigned four bodily fluids to the four basic elements of air, water, fire and earth: blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile. It was believed that an imbalance in the mixture of these humors would cause disease, but also determine the different characters of people. Thus, the yellow bile belonged to the fire and circumscribed the character of the choleric, who often tries to communicate with the motto “I’m overflowing with bile!”. Read more >

Today, we know that the development of gallstones is actually associated with an altered composition of the bile. Many accounts show that people have been plagued by gallstone disease for centuries, but there were only non-surgical therapies available to relieve their symptoms.

Wound physicians intervened only when gallstone-containing abscesses broke through to the outside. When the prerequisites for abdominal surgery were created with antisepsis and general anesthesia in the 19th century, there was a rapid increase in knowledge in the field of surgical therapy of gallbladder and bile duct stones as well as new diagnostic procedures: Via administration of a contrast medium, imaging of the biliary system was sought in order to localize any stones.

In 1882, Karl Langenbuch succeeded in performing the first gallbladder removal, and in 1890, Ludwig Courvoisier became the first surgeon to dare to open the common bile duct to remove a stone there and restore bile flow. The particular difficulty was to create a suture-tight closure of the bile duct. Many surgeons at that time refrained from surgical therapy of the bile ducts, knowing that a “biliary leak” of the duct would result in serious complications.

The saving idea to ensure bile drainage came from Hans Kehr in 1895, who invented the T-drainage, which is still used today. This is a very thin plastic tube that is inserted into the common bile duct and passes through the abdominal wall, allowing bile to drain freely. Once wound healing in the bile duct area is complete, the drain can be removed without complications.

In the following decades, there were still various surgical and diagnostic improvements, but the basic surgical therapy hardly changed. The development of the ERCP examination by Ludwig Demling in 1974 (ERCP stands for Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreaticography), a special X-ray contrast imaging of the bile ducts that simultaneously offered therapeutic possibilities, was groundbreaking (Fig. 8).

Last but not least, the development of minimally invasive surgery (Figs. 9 to 15) since 1985 revolutionized surgical procedures in the area of the gallbladder and bile ducts and has since made it possible to offer patients a much more comfortable surgical therapy.