Extra Information

Warning

The diseases described on the following pages contain images and film material taken during operations. Decide for yourself if you want to see these images. Please also note our imprint and the legal information. The Baermed practice assumes no liability. Do you really want to see the page!

Intestine

Topics

- Intestine and intestinal diseases

- Diverticulosis and diverticulitis

- Intestinal obstruction

- Colon cancer

- Chronic inflammation in the intestine

- Hemorrhoids

- Cancer of the rectum

1. Intestine and Intestinal diseases

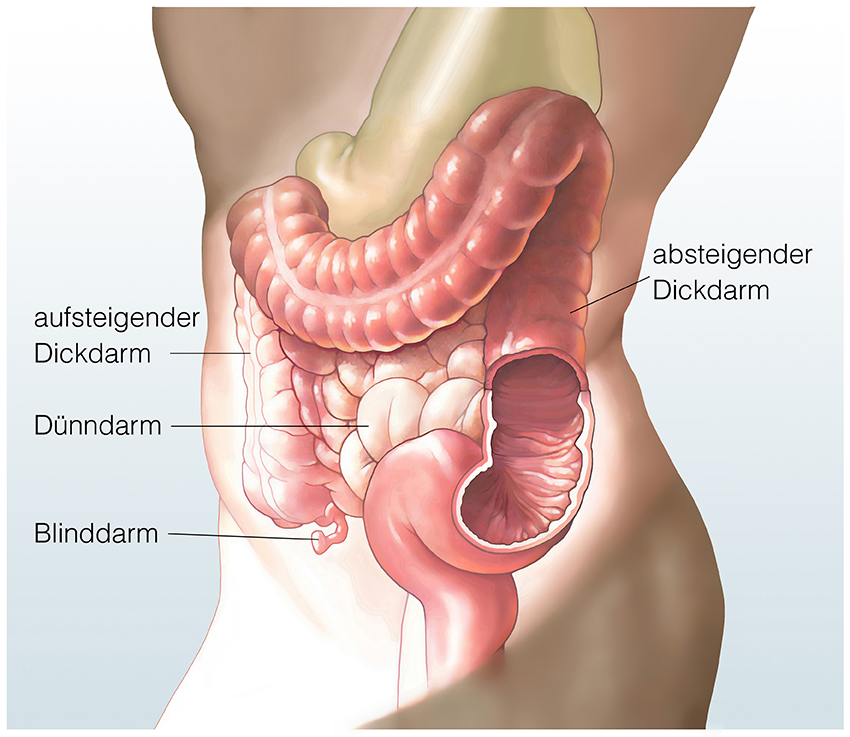

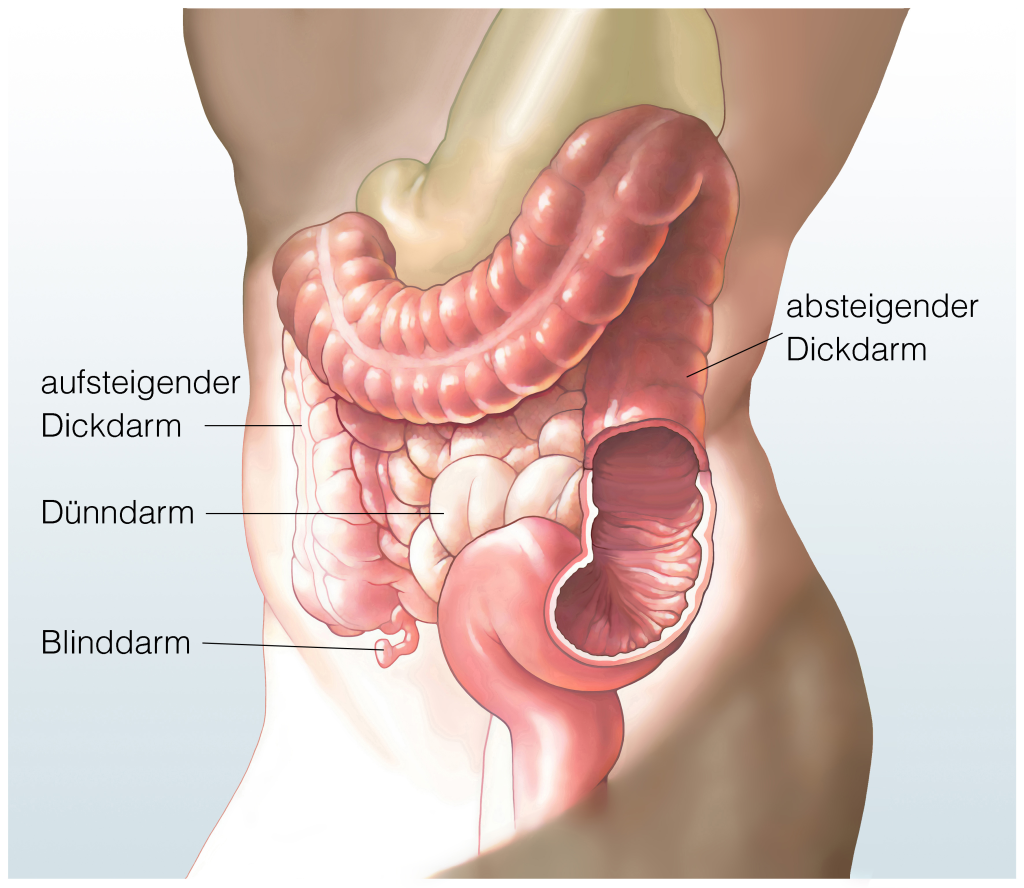

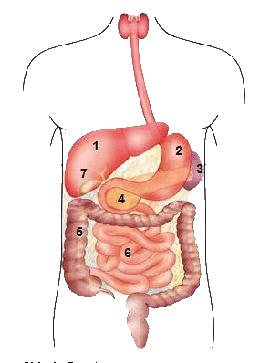

The intestine and its sections

Our intestine consists of several, very different sections (see Fig. 1): The short duodenum, which receives the food pulp directly from the stomach; the small intestine, a thin “tube” about four to five meters long; and the large intestine, about 1.2 meters long. The many loops of the small intestine are relatively free to move in the abdominal cavity and, in comparison to the large intestine, are supplied via various blood vessels, since many food components (sugar, proteins) are absorbed directly from the food into the blood here. The large intestine (colon) “frames” the loops of small intestine distributed in the middle and lower abdomen and is divided into different sections.

1 Liver

2 Stomach

3 Spleen

4 Pancreas

5 Large intestine

6 Small intestine

7 Gall bladder

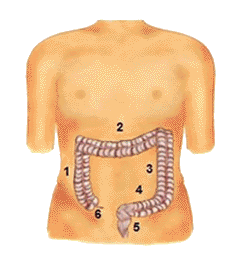

1 Colon ascendes

2 Transverse colon

3 Colon descendent

4 Colon sigmoldeum

5 Rectum (rectum)

6 Appendix

Where is the colon located?

The large intestine (colon) is the last part of the digestive tract and “frames” the loops of small intestine distributed in the middle and lower abdomen. Furthermore, the colon is divided into different sections (see Fig. 2):

Section 1:

The first part of the large intestine is located in the right lower abdomen, where the small intestine joins in such a way as to form a piece of intestine several centimeters long (cecum), which ends blindly and has a thin appendage called the appendix or vermiform appendix.

Section 2:

Above the confluence of the small intestine, the ascending part of the colon begins (ascending colon). It pulls upward, almost to the liver, and then describes a bend (right colonic flexure).

Section 3:

This is followed by the section of the colon running horizontally from right to left in the upper abdomen (transverse colon). This piece of colon is held in place by a “fat skirt” that is fused to the intestine and is called a “large mesh.” Arriving below the spleen in the left upper abdomen, the colon again describes a bend (left colonic flexure).

Section 4:

The descending colon moves toward the left lower abdomen (descending colon).

Section 5:

Thereafter, the colon describes an S-curve and is called the sigmoid colon, or sigma for short. The large intestine ends here, followed by the last part, the rectum.

Section 6:

The rectum is 16 centimeters long and merges into the anus.

In the middle of this “large intestine frame”, below the small intestine, several large blood vessels are found, originating centrally from the aorta and then running in a protective layer of tissue, which radiate to the colon and rectum.

The surgeon’s precise knowledge of which vessel supplies which segment of bowel is essential for good colon surgery and must be well considered in complex operations in this area.

How does the colon work?

In addition to its function as a digestive organ, the entire intestine also has important motor and immunological functions. Even in a fasting state, periodic waves run from the esophagus to the rectum via the smooth intestinal muscles, keeping the small and large intestines in continuous motion so that the food pulp is transported further. In this process, the loops of the small intestine move faster compared to the large intestine, so that the transit times of the food pulp in the small intestine are relatively short.

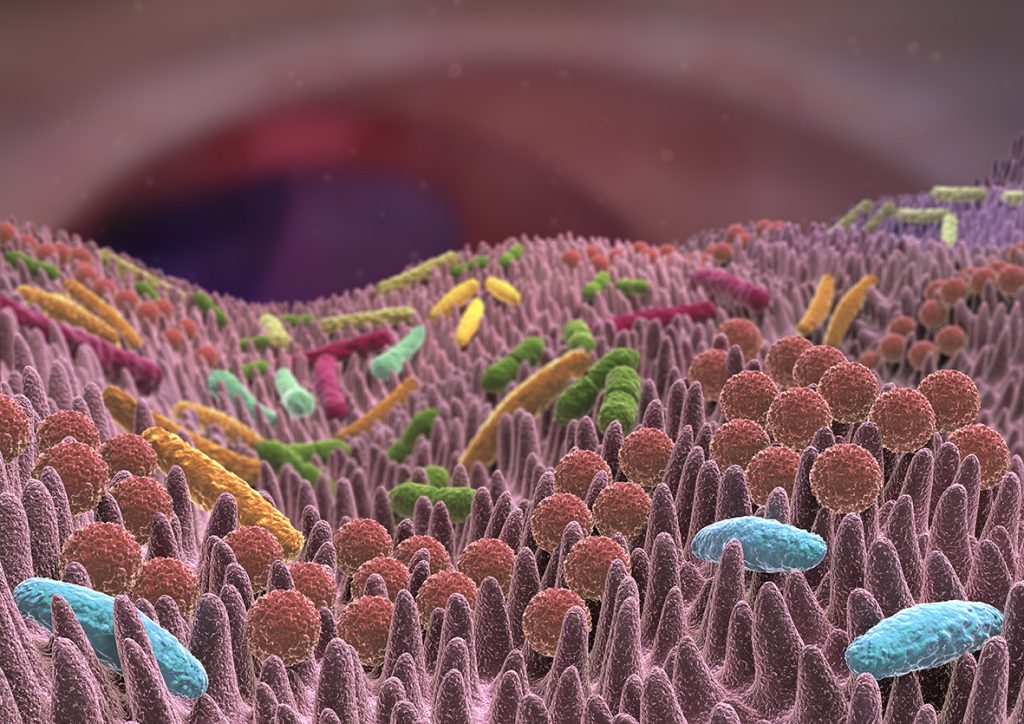

At the same time, the mechanism of rapid “transport” counteracts an excessive number of bacteria. In the large intestine, the passage times become longer so that the liquid food pulp from the small intestine can be thickened at rest.

The main task of the colon is to remove large amounts of water from the liquid intestinal contents and return it to the body. This is achieved by the intestinal motor system in such a way that there are not only forward movements of the loops, but also backward movements. At the same time, which is completely normal and desirable, the bacterial count increases dramatically here. Read more >

The healthy intestine has a wide variety of barrier mechanisms against these bacteria and produces certain proteins that have an almost disinfecting effect and are found on the intestinal mucosa. Nevertheless, certain intestinal regions are increasingly interspersed with lymph nodes and take on other immunological tasks to defend against germs.

Both surgical interventions and other diseases of the intestine can disrupt this finely tuned system with serious consequences and lead to classic problems of intestinal surgery: After surgical interventions, the intestine stops its “own movement” as a reaction to the manipulation that has taken place. As a result, the food pulp and the air contained in the intestine are not transported further. The intestine has paralysis (atony). Therefore, after bowel surgery, attention is focused on the paralysis, which must be overcome with special measures.

2. Diverticulosis and Diverticulitis

Symptoms, Treatment, and Surgery

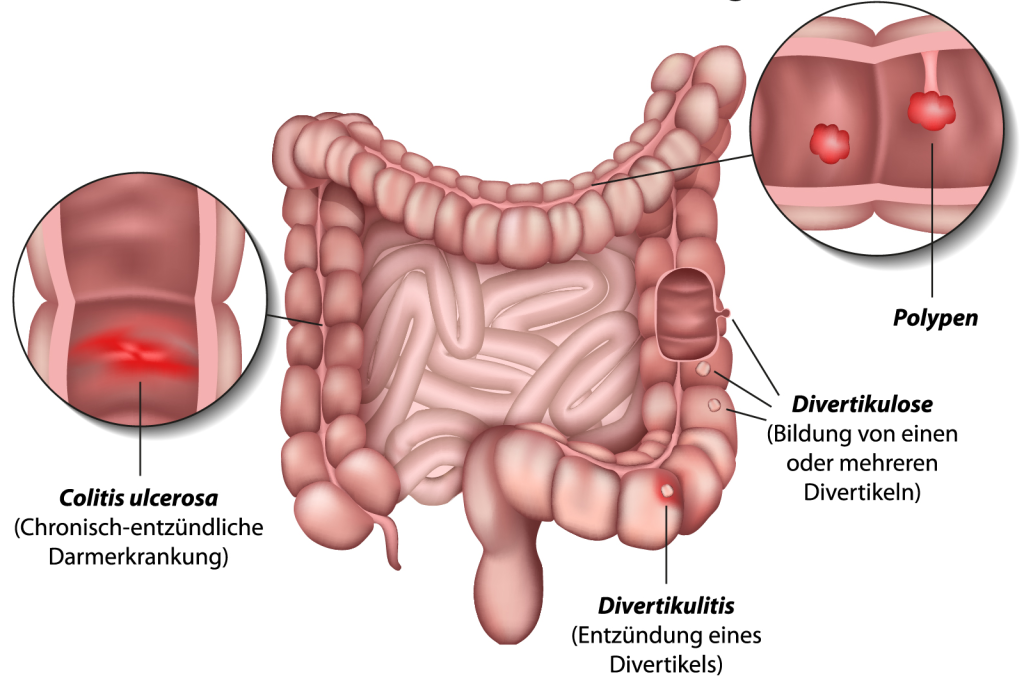

What is diverticulosis and what is diverticulitis?

According to current doctrine, the development of diverticulosis is caused by several factors. If chronic constipation occurs in humans due to a diet low in fiber, little physical activity and limited fluid intake, pressure rises sharply, especially in the sigmoid region. In this “high-pressure zone”, a permanent, local structural change of the intestinal wall occurs over time, which is also called “diverticulosis”.

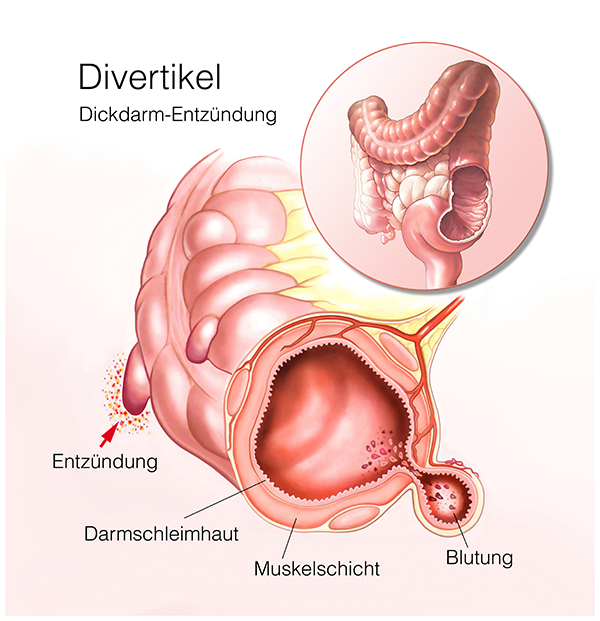

What happens in this structural change? Simplified, the intestinal wall is composed of three layers: On the very inside lies the mucosa, followed by a firmer supporting layer, which in turn is surrounded on the outside by a muscular mantle. Due to the high pressure inside the intestine, the mucosa in the area of muscular weak points presses outwards at certain points like a finger on a glove. If these protrusions occur in many places, especially in the sigmoid colon, the condition is referred to as diverticulosis (Fig. 5). In summary, diverticulosis is a structural change in the intestinal wall that may or may not lead to complications.

Diverticula are one of the most common colon findings in Europe in patients older than 50 years of age, with 70% of those affected having little or no symptoms. At most, they complain of occasional pain or cramping in the left lower abdomen, with alternating episodes of diarrhea and constipation. Read more >

Diverticulitis is the term used when inflammation of the diverticula occurs. This inflammation, in contrast to the purely structural change of the intestinal wall, has a real disease value. If stool and bacteria accumulate in these protrusions, it can cause inflammation, often accompanied by pain and fever. Often, acute diverticulitis is treated as an outpatient by the primary care physician or gastrointestinal specialist.

However, acute complications can also occur as part of the inflammatory reaction, with bleeding, abscesses or perforations of the intestinal wall being the result. If diverticulitis occurs intermittently over a period of years, the constantly recurring inflammation can lead to scarring and narrowing of the bowel. The full picture of such a narrowing of the intestinal lumen is complete intestinal obstruction, a complication that always requires surgery.

Symptoms of diverticulitis

Patients can only develop diverticulitis if diverticula are already present in their bowel. However, the doctor and patient often do not know whether this is the case. In western industrialized nations, however, more and more patients know whether they suffer from diverticula or not.

The increasing number of colonoscopies for cancer screening certainly plays a major role, with diverticula found by chance always being documented as well. The classic symptoms of diverticulitis include fever, diffuse lower abdominal pain on the left side, and constipation alternated with episodes of diarrhea.

But beware: there are countless other causes of diarrhea besides inflammatory bowel disease, including classic stomach flu, worms, traveler’s diarrhea, food poisoning and more. A tumor can also make itself felt for the first time in the form of these complaints.

Diagnosis and clarification of diverticulitis

The responsible physician must first try to delineate the above-mentioned clinical pictures by asking the patient as specific questions as possible: How often does diarrhea occur? Is there any additional mucus or blood discharge in the process? Does bowel movement cause pain or cramps in the lower abdomen? Are there episodes of fever in the course of such episodes? What are dietary and lifestyle habits? Has the patient noticed severe weight loss or a performance slump? Read more >

Following the questioning, a thorough examination of the abdomen is necessary to locate the site where the pain mainly occurs. In diverticulitis, the examining physician may occasionally palpate a type of “roller” in the left lower abdomen, causing significant tenderness.

The physical examination always includes a rectal examination. A blood analysis completes this initial interview and examination. The synthesis of interview, physical examination and various laboratory results decides which further diagnostic measures should be initiated. What methods are available for this?

Abdominal ultrasonography provides a basic orientation as well as an assessment of whether there is free fluid in the abdomen. The quality and significance of this ultrasound examination depends to a large extent on the experience of the physician performing it. However, abdominal ultrasonography is often inappropriate for the diagnosis of diverticulosis. In the case of acute inflammation, however, the extent of the inflammation and any abscess can be easily assessed.

X-ray abdomen overview image

The X-ray abdomen overview image basically shows free air as a black area. Thus, if air escapes from the intestine during an intestinal perforation, it collects at the highest point within the abdomen and shows up on the x-ray as a black crescent directly below the diaphragm. Read more >

Computed tomography

Computed tomography (Fig. 6) has become increasingly important in the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis in recent years. The CT scan can show changes in the intestinal wall well, in some cases even individual diverticula. Furthermore, the CT gives good information about any abscesses and free air. During the same examination, many other causes of the patient’s complaints can be ruled out.

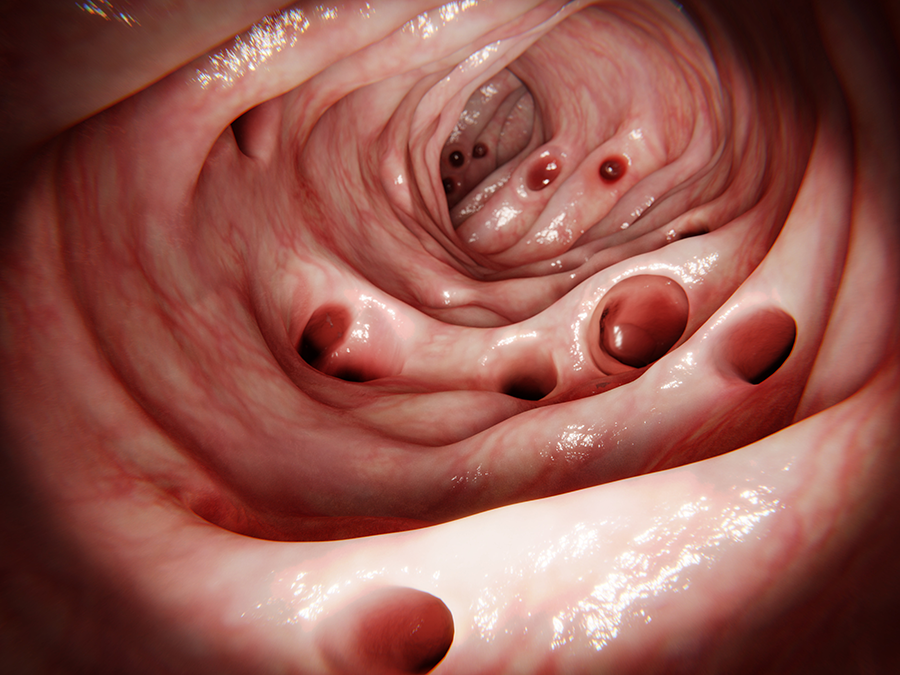

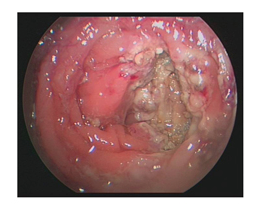

Colonoscopy

The indication for colonoscopy (Fig. 7) must be differentiated. In the acute inflammatory phase, colonoscopy is often not performed due to the high informative value and low complication rate of computed tomography, since inserting the endoscope into an inflammatory bowel carries the risk of perforation. Colonoscopy is performed only after the acute episode has healed. However, because diverticulosis, like colon tumors, increases with age, colonoscopy is ordered in every patient over the age of 50.

Diverticulitis treatment

The occurrence and nature of complications associated with diverticulitis determine whether conservative (drug) or surgical therapy must be initiated first.

If it is an inflammatory episode without acute bleeding or destruction of the intestinal wall, the disease is treated conservatively. The main measures are intestinal immobilization by food restriction with free drinking, feeding through a central venous catheter, antibiotic administration, and administration of antispasmodic drugs. No laxatives (purgatives) are given or laxative measures are performed from the rectum for fear of destroying the intestinal wall in the area of infection. Once the phase of inflammation subsides, the patient can resume eating foods rich in fiber that do not cause flatulence.

The so-called “elective”, i.e. planned operations for diverticulosis or diverticulitis are performed in the following cases: Read more >

- Diverticula have been detected by colonoscopy.

- At least one severe inflammation has already taken place, which had to be treated with antibiotics and may have required hospitalization.

- Recurrent inflammation of the sigmoid colon and/or stenosis of the colon have been demonstrated.

- In an inflammatory episode, an abscess, a collection of pus in the abdomen, has developed around the inflamed bowel.

- Emergency surgery is indicated when breakthrough of bowel contents into the abdominal cavity is demonstrated or at least suspected.

The open surgery

Through a 10 to 15 centimeter vertical incision from the belly button to the pubic hairline, the abdominal wall is cut in layers. The peritoneum is opened and the view is kept clear with several hooks so that the entire lower abdominal cavity can be seen clearly. First, the inflamed portion of the colon is visited, and the surgeon determines how much of the altered colon needs to be removed. The colon is then carefully detached from the peritoneum at the side. Careful attention must be paid to the ureter on the left, which pulls below the suspensory ligament (mesentery) of the sigmoid in this area.

The diseased section of bowel is dissected free, and the feeding blood vessels are cut so that the sigmoid can be well drained. Once the bowel segment is exposed, it is cut above and below the diseased area using a special stapling suture device that simultaneously cuts and closes. Two blind ends are created, which are joined together either by hand or with a special suturing device inserted into the bowel through the anus. Blood dryness is checked and two silicone drains are inserted. After that, the abdominal wall is closed again in layers.

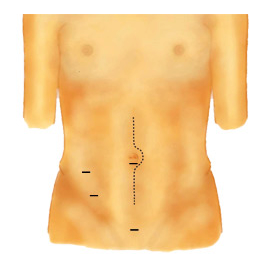

The laparoscopic surgery

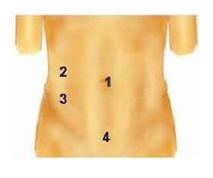

Today, minimally invasive surgery is considered the method of choice for the removal of diverticulum-bearing bowel segments (Fig. 8). The keyhole method is used especially in patients with known diverticulosis and multiple episodes of diverticulitis. However, if complications are already present, such as intestinal obstruction, intestinal perforation, or abscess, this method often cannot be chosen. This technique often has to be avoided even in an acute flare-up of inflammation. Read more >

1) 10mm for optics (later 20 mm)

2) 5mm

3) 12mm

4) 10 mm (later for gut 3cm)

Three more such guide sleeves are inserted into three further small skin incisions of five to ten millimeters under camera control. Working instruments, such as forceps and ultrasound dissectors, can now be inserted via these additional access points. Read more >

Step 1:

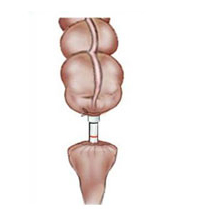

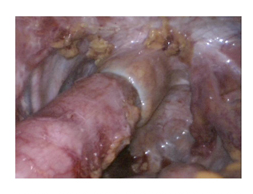

In a first step, suspensory ligaments or adhesions are cut and the diseased section of bowel is dissected free. This is followed by transection of the bowel below the diseased area using a laparoscopic stapler (Fig. 9).

The intestinal part with the diseased intestinal tissue is packed into a small sterile plastic bag and brought in front of the abdominal wall via an access at the pubic hairline. The diseased bowel section is then cut and removed (Fig. 10).

Step 2:

The next step is to insert the head of a stapler into the remaining, healthy piece of bowel, which is sutured and placed back into the abdominal cavity (Fig. 11).

Step 3:

Now the two ends of the intestine must be joined together again. For this purpose, a special suturing device is inserted via the anus, which grasps the headpiece lying in the abdominal cavity and sutures it with staples (Fig. 12).

Step 4:

Subsequently, it is possible to test whether the newly created connection is also tightly sealed. For this purpose, a blue dye is injected into the intestine from the anus. If no leakage of blue fluid into the abdominal cavity is seen, the connection is tight. As a final step, all abdominal incisions must now be closed again in layers.

Acute diverticulitis

Surgery for acute diverticulitis needs to be viewed in a more differentiated manner. If diverticulitis leads to destruction of the intestinal wall and extensive infection from feces in the abdominal cavity, the patient requires emergency surgery. In this situation, the surgeon must decide whether or not to immediately re-suture the bowel after removing the diseased section of colon.

If the abdomen is inflamed, there is a high risk of a poorly healing bowel suture with a possible suture leakage. In this situation, the surgeon has two options: Read more >

Surgical option 1:

He removes the diseased colon and temporarily drains the upper end through the abdominal wall as an artificial colon outlet and closes the lower end. This is referred to as a colostomy.

The intestine is temporarily not restored to continuity. The patient can recover and you wait until the inflammation in the left lower abdomen has stopped. After about three months, surgery is performed again, with the colostomy moved back and the ends of the colon sutured back together.

Surgical option 2:

In the second option, the surgeon rejoins the intestinal segments after resection, but relieves this segment by draining the intestinal contents further upstream via an artificial small bowel outlet. Here, the stoma is also moved back in a second surgery after the infection has receded. Compared to the first variant, this intervention is much smaller.

What happens after the treatment?

Patients with a severe course of disease are initially transferred to the intensive care unit for monitoring after surgery. There, they continue to receive antibiotics, balanced infusion therapy and sufficient pain medication. The most important blood values are checked here as needed.

If the patient is stable, he is transferred to the ward after a short time. He is usually allowed to drink again in sips after one to two days. Because the surgeon operated in an area that was prone to inflammation, he is reluctant to stress test the new bowel suture. This means that the nutritional build-up does not begin until about the fourth day with liquid food, and that a slow build-up of food with soup takes place Read more >

The patient is mobilized early and receives respiratory exercises. On about the sixth day, or earlier if there are no complications, the patient can leave the hospital. Patients who have been treated intraoperatively with a stoma learn the necessary handling of hygiene and materials under the guidance of a stoma consultant.

In principle, after a successful surgery without complications, patients have nothing special to consider. It may take some time to return to normal, soft stools.

A high-fiber diet, sufficient fluid intake and adequate exercise are important. There is no need to follow a restrictive diet.

Historical

As recently as 150 years ago, about two-thirds of visceral surgery patients died. Even in minor procedures such as finger and toe amputations, 10% of patients died. Reasons for this high mortality were the lack of anesthesia, antisepsis, and the problem of “shock.” This latter phenomenon is caused, for example, by high blood loss or by washed-in bacteria and can be fatal. Only after breakthrough discoveries, which to this day are the firm foundation of any major abdominal surgery, did the results improve. Read more >

In 1844, the first anesthesia with nitrous oxide was performed by Horace Wells, and in 1901, Karl Landsteiner discovered the blood groups of humans. This opened up the possibility for the first time to perform blood transfusions during major surgical operations and to successfully treat hemorrhage shock. The greatest achievement, however, was Ignatz Philipp Semmelweiss’ realization that the wound infections, which were usually fatal at the time, especially puerperal fever, were caused by poor hygiene of hands and instruments. Until then, thorough hand disinfection was completely unknown in hospitals. Doctors and nurses, without knowing it, carried the bacteria from one patient to another. Unfortunately, Semmelweiss was too far ahead of his time, so his appeals for hand disinfection with carbolic acid were not taken seriously at first, despite the proven effectiveness of Louis Pasteur, the famous discoverer of the bacteria.

It was the surgeon Joseph Lister from Glasgow who took up Semmelweiss’ ideas and successfully implemented them in his clinic in 1867: Before operations, the surgeons’ hands were washed with carbolic soap, and a carbolic solution was atomized over the surgical area during the operation. This significantly reduced the number of fatal complications after surgery. In the course of this knowledge, operating rooms were then created that could only be entered with a hood and mouth guard, so that the first major abdominal surgical procedures, which were then also performed aseptically, were more successful from 1880.

Exemplary for the spirit of optimism in abdominal surgery under these new conditions is the work of the surgeon Professor Ulrich Kroenlein, who worked and taught at the University Hospital Zurich since 1881. He translated the new hygiene ideas into measures in the hospital by having floors tiled, wooden bedsteads removed, and a new operating room built in the form of an amphitheater (student classroom). Kroenlein was one of the first surgeons to operate on acute appendicitis and was involved in the treatment of purulent peritonitis, a complication that occurs particularly after intestinal injuries.

In order to avoid such peritonitis caused by poor intestinal sutures (anastomoses), two other famous surgeons at that time were struggling to find new suturing techniques in intestinal surgery, Theodor Kocher and Vinzenz Czerny. “Intestinal resection has become an extraordinarily important and relatively frequent surgical procedure, by the correct performance of which the surgeon can preserve many a life otherwise irrecoverably lost,” wrote Theodor Kocher in 1894, introducing his continuous intestinal suture (Boschung U.: Milestones in the history of intestinal anastomosis. Swiss Surg 2003; 9: 99-104). Thus, as early as 1907, Sir Ernest Miles performed the first radical abdominoperineal resection for rectal carcinoma, a major operation in which the colon and rectum were completely removed.

For the removal of the diverticulum-bearing portion of the sigmoid loop, results became good especially when irrigation of the bowel before surgery, consistent antibiotic administration, and new suture techniques using today’s modern suture materials were introduced. A major step towards low complication rates, short hospital stays and good postoperative results has been achieved by the recently introduced minimally invasive laparoscopic sigmoid resection. Together with the concept of “fast track” surgery (gentle, low impact surgery for patients), sigmoid resection for diverticular disease has now become a safe surgery with low complication rates.

3. Intestinal obstruction

Symptoms and surgery in acute ileus

Ileus

Intestinal obstruction (ileus) is an interruption of passage in the small or large intestine and is a life-threatening situation. In an intestinal obstruction (ileus), the intestinal contents remain in one place in the intestine. The intestinal passage is either blocked by obstacles (so-called mechanical intestinal obstruction) or the intestine is no longer able to move its contents forward (so-called functional intestinal obstruction). In addition to complete bowel obstruction, there is also incomplete bowel obstruction (known as subileus).

The disease can be life-threatening. If suspected, affected individuals should not eat or drink anything until the examination. Patients with bowel obstruction must seek immediate medical attention and in many cases surgical intervention is necessary.

Where are the small intestine and large intestine located?

Our intestine consists of several, very different sections: The short duodenum, which receives the food pulp directly from the stomach; the small intestine, a thin “tube” about four to five meters long; and the large intestine, about 1.2 meters long. The many loops of the small intestine are relatively free to move in the abdominal cavity and, in comparison to the large intestine, are supplied via various blood vessels, since many food components (sugar, proteins) are absorbed directly from the food into the blood here. The large intestine (colon) “frames” the loops of small intestine distributed in the middle and lower abdomen and is divided into different sections.

The first part of the large intestine is located in the right lower abdomen, into which the small intestine joins in such a way as to form a piece of intestine several centimeters long (caecum), which ends blindly and has a thin appendage called the appendix or vermiform appendix.

Above the confluence of the small intestine, the ascending part of the colon begins (ascending colon). It pulls upward, almost to the liver, and then describes a bend (right colonic flexure).

This is followed by the section of the colon running horizontally from right to left in the upper abdomen (transverse colon). This piece of colon is held in place by a “fat skirt” that is fused to the intestine and is called the “large mesh.” Arrived under the spleen in the left upper abdomen, the large intestine describes a bend again (left colonic flexure). Read more >

The descending colon moves toward the left lower abdomen (descending colon).

Thereafter, the colon describes an S-curve and is called the sigmoid colon, or sigma for short. The large intestine ends here, followed by the last part, the rectum.

The rectum is 16 centimeters long and merges into the anus. In the middle of this “large intestine frame”, below the small intestine, several large blood vessels are found, originating centrally from the aorta and then running in a protective layer of tissue, which radiate to the colon and rectum. The surgeon’s precise knowledge of which vessel supplies which segment of bowel is essential for good colon surgery and must be well considered in complex operations in this area.

How do the small intestine and large intestine work?

The food pulp digested in the stomach is mixed with bile and juices from the pancreas in the duodenum and broken down into components such as sugars, fats, and proteins.

The good blood circulation in the small intestine ensures that these “building blocks” can be absorbed into the blood and further processed by the body. All indigestible components eventually enter the large intestine. This removes the water from the still liquid food pulp. Read more >

But how does the intestine transport the food pulp further and how does it thicken it at the end? Even in fasting people, periodic waves run from the esophagus to the rectum over the smooth muscles of the intestine and keep it constantly moving so that the chyme is transported further. In this process, the loops of the small intestine move faster compared to the large intestine, so that the passage times of the food pulp in the small intestine are relatively short. At the same time, this mechanism counteracts the rapid “carriage” of excessive numbers of bacteria that naturally occur in the intestine.

In the large intestine, the food pulp lingers longer so that it can be thickened at rest by dehydration. This is achieved by the intestinal motor in such a way that there is not only a forward movement of the loops, but also a backward movement. At the same time, which is completely normal and desirable, the number of bacteria in the intestine increases dramatically.

The healthy intestine has a wide variety of barrier mechanisms against these bacteria and produces certain proteins that have an almost disinfecting effect and are found on the mucous membrane. Diseases such as intestinal obstruction can severely disrupt this finely tuned system and thus lead to serious consequences.

What is intestinal obstruction?

Intestinal obstruction (ileus) can affect both the small intestine and the large intestine. It is understood as a passage disorder of the intestinal contents, which in most cases has mechanical causes. But what does that mean? A section of the small or large intestine is displaced from the inside or outside, preventing the passage of the food pulp. This occlusion may be complete (ileus) or incomplete (subileus). From the inside, for example, a mechanical obstruction can be caused by a growing tumor or by swallowed objects in children. Read more >

Since the intestine is a soft tube, its opening can also be squeezed shut from the outside. This often occurs due to connective tissue strands (brides) that cross the abdominal cavity and in which the mobile small intestine can quickly become entangled. This is referred to as a brittle ileus, which often affects patients who have had previous surgeries, since surgeries can fundamentally lead to the formation of strands.

The second form of mechanical ileus is strangulated ileus, which usually involves the mobile small intestine. In this process, the loops of small intestine rotate around their own axis, so to speak, and thus cause an interruption in the blood supply to the intestine. The result is a lack of oxygen supply to the intestinal tissue as well as a passage blockage for the food pulp. Furthermore, the small intestine can also become stuck in the hernial sac of a wide variety of hernias, which can also result in an ileus.

The colon, on the other hand, which is attached to the peritoneum in many places, is most commonly affected by a passage disorder caused by a tumor that either grows in the colon or presses on it from the outside. In addition to the mechanical causes now mentioned, paralysis of the intestinal muscles can also be the cause of ileus (paralytic ileus). This means that the periodic self-movement of the intestine comes to a standstill, the food pulp is not transported further and the passage is impeded. This may be the case in severe metabolic disorders or generalized bacterial infections, abdominal trauma as well as after major abdominal surgery.

But why is ileus so dangerous? The congestion of the food pulp alone, regardless of the location in the intestine and the cause, leads to severe overstretching of the intestinal wall. This triggers a sequence of reactions in the body, which will be described below and which ultimately lead to the dangerous “ileus disease”.

The overstretching of the intestinal wall due to “congestion” leads to a circulatory disturbance of the same, which locally triggers a lack of oxygen in the tissue. This causes the intestines to stop moving, resulting in a drastic increase in the number of bacteria, which then secrete certain toxins. After these events, the intestinal wall, if you think of it as a “barrier,” is weakened in several ways. There is an influx of fluid into the intestine and intestinal wall, whereby the “water” is previously, in the sense of a pathological redistribution, withdrawn from the vascular system and causes circulatory weakness in the patient. In addition, the toxins of the bacteria can now penetrate the weakened barrier of the intestinal wall, enter the circulation and trigger a shock event there via complicated mechanisms, which can affect other organs, such as the kidneys or lungs.

Symptoms of intestinal obstruction

“The day started like any other. I had breakfast and then went to work. After lunch, I suddenly got a cramping abdominal pain. The pain came and went away. During the afternoon, I could only sit curled up in my chair. My boss then sent me home. When I arrived home, I had to vomit several times in a gush. My abdomen became increasingly distended and the pain was getting worse. I only felt a little better when I was lying down with my legs drawn up. A friend, who wanted to visit me spontaneously in the evening, finally drove me immediately to the clinic to the emergency ward.”

This description by an affected person contains many of the complaints that a patient with impending ileus may usually report. Cardinal symptoms are vomiting (possibly even in a gush) and severe, episodic, colicky abdominal pain. In many cases, the abdomen is very bloated and tender. Depending on which section of the bowel the obstruction is in, patients may no longer have bowel movements or wind discharge. Read more >

A frequently asked question is why you get crampy colic. As soon as the intestine is closed for any reason, it tries with all its might to fight against this obstacle. This struggling against an obstacle causes the colicky pain. In paralytic ileus, on the other hand, the intestine quickly becomes paralyzed: “It becomes deadly quiet in the abdomen,” which means that the physician can no longer hear any intestinal sounds through his stethoscope.

Necessary clarifications and diagnostic possibilities

Depending on which section of the intestine is at risk of obstruction, the above-mentioned symptoms may occur in very different degrees and order. Patients with small bowel ileus are more likely to complain of crampy abdominal pain and vomiting.

A colonic ileus usually causes significant irregularities in bowel movements before abdominal pain occurs. For this reason, other clinical pictures must first be differentiated by means of a precise questioning of the doctor treating you. In the case of bowel obstruction, the primary aspects of interest are the time when the pain started, the type of pain (dull, stabbing, colicky cramps), whether the patient had to vomit, and when he or she last had a bowel movement. He should also be asked about past abdominal surgeries (appendectomy, hysterectomy, gallbladder surgery, other stomach or intestinal surgeries) and other general illnesses.

This is followed by further investigations: Read more >

Abdominal palpation

Examination with the hands often reveals a bloated, tender abdomen that is very sensitive to pain. Furthermore, palpation of the abdomen looks for abnormal masses. By gently tapping the abdomen with the fingers, air accumulation can be detected. A very informative examination step is listening to the abdomen with a stethoscope to assess bowel sounds. With increasing bowel obstruction, so-called “high-pitched” bowel sounds may be heard at first, and later also “ringing” bowel sounds. After prolonged duration of mechanical ileus and transition to paralytic ileus, bowel sounds are no longer audible. The type and quality of bowel sounds are a very important sign of bowel obstruction for the surgeon.

Rectal examination

Examination of the rectum is a must for all acute abdominal complaints. However, pain and blood on the fingerstall are fairly unspecific and can also be found in other intestinal and abdominal diseases.

Abdomen blank image

X-ray of the abdomen in the standing and supine position provides an enormous amount of information regarding intestinal obstruction. On the images, you look for fluid levels and what’s called free air in the abdomen. If such levels are present, this is an almost certain sign of the presence of bowel obstruction. Based on the localization of the fluid levels, it is possible to estimate approximately where the bowel is occluded. So-called “standing bowel loops” are also a typical sign of the presence of an intestinal obstruction. Due to the obstruction of the intestine, gases accumulate in front of the obstruction, the intestinal loops inflate and give the impression on the X-ray that they are standing in the abdomen.

Ultrasound examination

An ultrasound of the abdomen provides a quick opportunity to make important statements regarding the following questions concerning the affected bowel loops: Are they filled with fluid? Is the intestinal wall thickened? Is there still any intrinsic movement of the intestinal loops?

Contrast agent administration

If small bowel ileus is suspected without strangulation, oral administration of water-soluble contrast may be attempted. On the one hand, this agent has a laxative effect, on the other hand, an X-ray can be taken after certain periods of time to see if the fluid has run up to the colon in an adequate amount of time. This allows you to better determine the location of the closure.

Blood tests

A blood test can make a certain contribution to clarify the cause of the intestinal obstruction. In contrast, only certain causes can be seen in the laboratory results, but not the bowel obstruction itself.

Computed tomography

If the cause of the bowel obstruction cannot be found with the above-mentioned examinations or if a mass is palpated on abdominal palpation, a CT scan can also be performed in certain cases as a supplementary diagnostic test.

A surgeon can only answer the most important questions by looking at the patient’s medical history and various examination results together: Is it a small bowel obstruction or a large bowel obstruction? Is the occlusion mechanical or paralytic? Is it complete or partial? Is the patient suffering from another, previously unknown disease (tumor, inflammation, hernia)? Does he have to operate on the patient immediately or can he wait under close supervision?

At least one severe inflammation has already taken place, which had to be treated with antibiotics and may have required hospitalization.

Recurrent inflammation of the sigmoid colon and/or stenosis of the colon have been demonstrated.

Emergency surgery

In an inflammatory episode, an abscess, a collection of pus in the abdomen, has developed around the inflamed bowel. Emergency surgery is indicated when breakthrough of intestinal contents into the abdomen is demonstrated or at least suspected.

Acute intestinal obstruction – surgery and treatment

Once the diagnosis of acute intestinal obstruction is established, basic measures are taken, regardless of what form of ileus it is. Since all patients suffer from a serious disturbance of their fluid balance, but at the same time have to remain fasting, they are first given a large venous access, whereby a soft plastic tube is pushed through a large needle into a central blood vessel.

This CVC (central venous catheter) is located either in the collarbone area or in the neck. Through this catheter, patients receive the necessary fluids as well as trace elements and medications (e.g. antibiotics). Since most patients have already vomited, a feeding tube is placed in them. This is a fine plastic tube that is advanced through the nose via the esophagus into the stomach. This allows the retained fluid from the stomach and intestines to be drained into a bag. These two measures, gastric tube and infusion, serve only to ensure a stable circulatory state and have no therapeutic effect whatsoever with regard to intestinal obstruction Read more >

Ileus disease

Sometimes patients with advanced “ileus disease” need to be treated in the intensive care unit. So how do you proceed? In paralytic ileus (i.e., non-mechanical), the above measures are taken and the underlying condition is treated at the same time. The procedure in this case tends to be nonoperative unless there is massive overdistension of the bowel. In this case, special surgery must be performed to relieve the bowel.

What about mechanical ileus? Mechanical ileus is often due to adhesions in the abdominal cavity and predominantly affects the small intestine because it is relatively mobile in the abdominal cavity. In the colon, mechanical obstruction is most often caused by a tumor. In both situations, surgical measures are necessary to remove the obstacle to passage and restore the continuity of the bowel. In this context, open surgery is the method of choice for the treatment of intestinal obstructions.

Depending on the patient’s condition, laparoscopic surgery may be attempted. Nevertheless, it is often necessary to switch to the open technique because the problem is either not seen properly or the cause is difficult to correct laparoscopically. Depending on where the obstruction is suspected to be (upper, middle or lower abdomen), the surgery involves making a vertical incision in the middle of the abdomen as an approach. Then, in a second step, all layers of the abdominal wall are carefully cut. Several hooks are used to stretch the edges of the incision so that the view of the abdominal organs is unobstructed. Now the entire abdominal cavity can be searched for the cause of the bowel obstruction.

The first thing the surgeon usually notices is the highly distended bowel loops in front of the passage obstruction (bride or tumor). Behind the occlusion, the so-called “hunger gut” is often found. At this point, the intestine is completely empty and quite thin, as no food has been transported through here for a long time. Once the site of the occlusion has been found, the cause is usually clear. In the vast majority of cases, these are simple adhesions that lead to kinking or strangulation of the bowel. The adhesions are cut sharply with scissors, and the bleeding is stopped with single stitches. As soon as the bowel has been freed from adhesions, its vitality must be checked, i.e. it must be checked whether the section of bowel that was kinked is still “alive”.

If the intestine moves on contact, its function is still preserved. Another vitality criterion is the color and blood circulation. If the color and mobility of the intestine are in order after the adhesions have been dissolved, the abdomen with all its layers can be closed again. Sections of the intestine that have been clamped off and are poorly perfused turn blue.

If the bowel does not become nicely pink after the cause of the obstruction has been removed, it must be assumed that the section of bowel in question has already died and therefore be removed. In this procedure, the bowel above and below the dead bowel portion is cut and closed with a special stapling device. Two blind ends are created, which are joined together again by two continuous seams. This is followed by checking for blood dryness, insertion of two drains, and layer-by-layer closure of the abdominal wall.

What happens after the operation?

Patients are usually monitored in the intensive care unit for one to two days after surgery. Above all, fluid intake is carefully balanced and constantly corrected. The patient receives adequate pain medication and often antibiotic therapy. A previously feared complication after surgery was the occurrence of leakage from the new intestinal suture with leakage of intestinal contents into the abdominal cavity. Fortunately, with good surgical technique and new suture material, this has become very rare. Read more >

It is important to check bowel activity once or twice a day postoperatively. This is done mainly by listening to the abdomen. After any abdominal procedure, the bowel may “strike” for the first few days. He is offended, so to speak, and refuses his transportation service. This is a normal reaction, but it will return in the first few days after surgery.

If the bowel resumes its activity, the patient can try to consume small amounts of tea or water. If the gastric tube does not deliver any gastric juice or delivers significantly less, the patient can be released from the previously inserted tube. Fluid amounts can now be increased daily. The diet begins first with soups, is then supplemented with stock and sauce, and finally the patient is allowed to eat finely chopped food and finally normal food. The skin sutures can be pulled on the tenth postoperative day. Patients can be discharged home within about eight days if they do well.

What needs to be considered in the future everyday life?

Many patients ask the doctor if there is anything they can do to prevent another bowel obstruction. Unfortunately, mechanical ileus cannot be prevented in any way. Any open surgery, even that of bowel obstruction, can sometimes lead back to adhesions in the abdomen. Patients can lead a completely normal life after such an operation, with no restrictions on eating and drinking, and they can also resume sports. In case of recurrence of symptoms such as pain or stool retention, patients should contact their physician in a timely manner. If an intestinal obstruction is the result of another underlying disease (tumor, diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease), the underlying disease must of course be treated professionally at the same time.

Historical

The symptom of intestinal obstruction was already known to Greek physicians in ancient times. They called this disease “ileus”, which means “full of mud”. This name was given because in the case of intestinal obstruction, the intestinal contents cannot be transported any further and accumulate in front of the obstruction. This liquid can look something like mud.

4. COLON CANCER

Diagnosis colon tumor and rectal tumor

Colorectal carcinoma

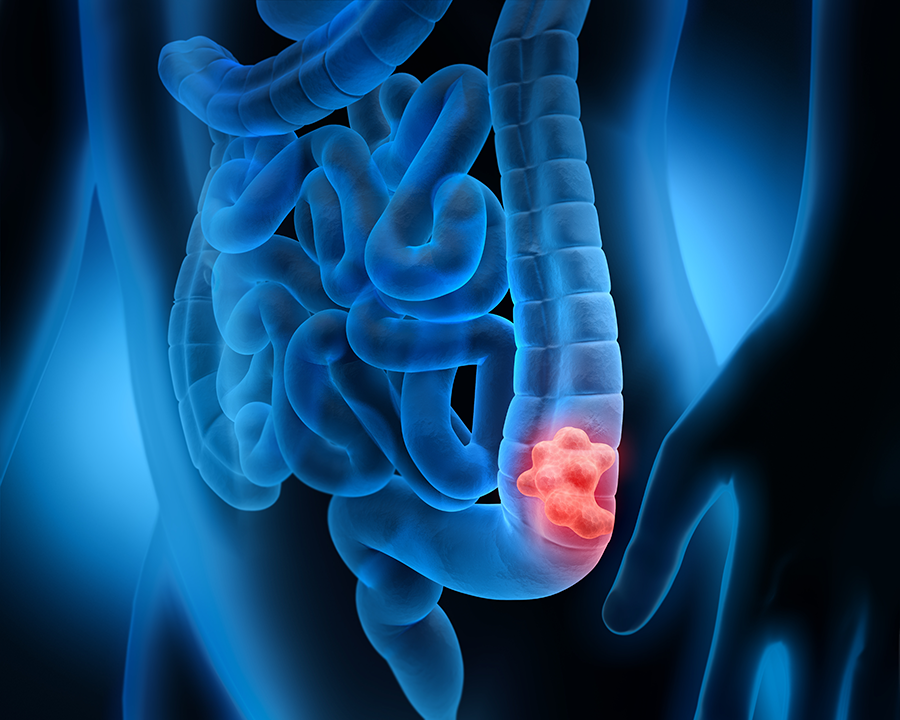

Cancers of the colon (known as colon carcinoma) and rectum (known as rectal carcinoma) are grouped together under the name colorectal carcinoma. In these, malignant growths occur in the mucosa of the intestine. People often talk about colorectal cancer, although other sections of the intestine (e.g. the small intestine) are more rarely affected.

The most common malignant colon and rectal tumors

In medicine, a basic distinction is made between primary and secondary tumors (metastases). In the colon, a primary malignant tumor would be a tumor that originates in the colon or rectum and has the property of forming metastases. The metastases from these tumors are transported via the lymphatic system to the liver and then to the lungs, where they can continue to grow.

The most common tumor in the colon is adenocarcinoma (lat. adeno = originating from glandular cells), which originates from the colon mucosa. If the same tumor is within 16 centimeters of the anus, it is called rectal cancer. Read more >

Other, rare carcinomas found are called mucinous (mucinous) adenocarcinomas or signet ring cell carcinomas. The external shape that the tumor takes in the intestine can also be very different: it can be pedunculated, crater-shaped and diffusely growing, or it can be ring-shaped constricting the intestinal clearing. Depending on the manifestation, the early symptoms that may be associated with this tumor are also very different.

The causes of the development of these carcinomas are not precisely known. Genetic, but also nutritional factors such as a high fat content in the diet are discussed. However, some risk factors are also fairly well established. These include certain pre-existing conditions of the intestine, such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, or familial poliposis coli. The latter is even considered a precancerous condition (precursor to a tumour), since the many proliferations of the intestinal mucosa (polyps) become malignant after a certain period of time. A known family history of colon cancer in the immediate family also increases the likelihood of developing such a tumor.

Symptoms of malignant colon tumors

Unfortunately, initial symptoms in patients with this tumor vary widely or may not be present at all. If the intestinal clearance is displaced, for example by the tumor, stool irregularities (diarrhea alternating with constipation) or colicky pain and flatulence may occur. Pedunculated tumors bleed more frequently and can thus cause gradual anemia in the patient. If a discharge of blood occurs in the area of the anus or if the patient discovers blood in the stool, he or she should consult a doctor immediately to clarify whether this is merely related to hemorrhoidal disease or has other more serious causes.

Necessary clarifications and diagnosis

Unfortunately, a wide variety of gastrointestinal diseases can cause the above-mentioned complaints, so the doctor must first ask a very detailed history, perhaps as follows: “How long have there been pains in the abdomen and stool irregularities? Are the complaints related to specific foods or overall food intake? Is there a marked loss of weight, a drop in performance?” Questions about blood in the stool or blood buildup on the stool are also very important. “Are there any close relatives with particular bowel diseases or people who have had colon cancer?” Read more >

Then the doctor will examine the abdomen and feel if there is significant distension, if there is palpable tumor, or if there are hernial orifices. A laboratory examination is certainly performed to get an overview of all organ functions and to rule out anemia, for example. Since the majority of carcinomas are found in the rectum, the slightest suspicion of a tumor in this area includes a digital examination of the rectum by the physician.

If the suspicion of colon or rectal cancer has been confirmed by this time, an additional rectoscopy and/or colonoscopy must be performed and tissue samples taken from all suspicious areas of the mucosa. Furthermore, an ultrasound of the abdomen will be done to evaluate the liver (metastases), gallbladder, bile ducts, pancreas and kidneys. Depending on the location and size of the tumor as well as other concomitant diseases of the patient, additional special examinations may be necessary, such as a CT scan, an endosonography of the rectum (the exact location of the tumor is very important for surgical planning), a heart ultrasound or a lung function diagnosis.

Surgery of rectal carcinoma (colorectal carcinoma)

If the diagnosis of colon or rectal cancer has been confirmed, surgical removal of the tumor is the treatment of choice. Depending on the stage of the tumor, this can definitely relieve the patient of his tumor condition. Conservative therapies, such as chemotherapy, are used only as adjuncts.

If the diagnosis of colon or rectal cancer has been confirmed, surgical removal of the tumor is the treatment of choice. Depending on the stage of the tumor, this can definitely relieve the patient of his tumor condition. Conservative therapies, such as chemotherapy, are used only as adjuncts.

Operation preparation

Prior to surgery, bowel irrigation is performed to prevent infection from germs when the bowel is removed and rejoined. For this reason, every patient also receives an antibiotic administration before the operation, which is continued for several days after the operation. The goal of colon surgery, regardless of the location of the carcinoma, is to remove the tumor-bearing section of the colon as well as the associated lymph nodes and to reanastomose (anastomosis = reunion of hollow organ parts) the colon areas. As an example, a right hemicolectomy will be described below. If this operation is performed, the tumor is located somewhere in the ascending part of the colon on the right side of the “frame”.

Two different surgical techniques are possible:

- The open surgery

- The laproscopic or minimally invasive surgery

Open surgery

The abdominal cavity is accessed through an incision that begins two to three transverse fingers above the navel, then arcs around it to the left and continues downward to the pubic hairline. Then the abdominal wall is cut and the abdominal cavity is opened. The surgeon first palpates all organs, such as the liver, spleen and stomach, by hand for orientation: Are there enlarged lymph nodes or metastases?

Then he looks for the ascending colon on the right side and the “cecum”, the part of the large intestine into which the small intestine flows. Indeed, if the tumor is very close to this junction, the surgeon must be very sparing with the removal of small intestine, since many bile acids are absorbed there. Then, based on the tumor location, the surgeon will mark the boundaries at which he wants to cut through the intestine. The suspensory ligaments between the colon and liver and the colon and stomach must be cut. Since parts of the ascending colon are fixed to the peritoneum, it is carefully detached from its support and mobilized toward the center of the abdomen. Particular attention must be paid to the ureter, which runs posteriorly in the peritoneum. Read more >

In the next step, the vessels running from the “center of the frame” outward to the colon are carefully dissected free in their tissue strand. At the required distance from the tumor, the bowel is clamped on both sides. The vessels that have already been dissected free are cut off, and the intestine is cut and removed at the two sites. The remaining stumps are disinfected, and the colon and small intestine are carefully sutured back together. A silicone drain is placed near the anastomosis and drained separately. After checking for blood dryness, the abdominal wall is closed again in layers. If a tumor is located in the transverse or descending part of the colon, the surgical sequence is the same as for hemicolectomy, with special consideration of the vascular supply and other details, except that a different area of the colon is affected.

The procedure becomes more complicated if the tumor is located in the rectum, since here the intestine already runs in the small pelvis and is therefore more difficult to access surgically. Curative therapy of rectal carcinoma is performed, for example, by anterior rectal resection. Access to the abdominal cavity is the same as for hemicolectomy. The surgeon then turns to the left lower abdomen and locates the tumor-bearing section of bowel. From the preliminary examinations, the surgeon usually knows at what level the tumor can be found. This knowledge is very important, especially in rectal tumors, because the distance from the tumor to the anus plays a major role in surgical planning, and especially when performing anastomosis in this area. In order to be able to resect bowel in the rectal region, the descending colon as the advancing part of the bowel must first be detached from the substrate and mobilized.

In the case of malignant tumors, the associated lymph nodes on the large vessels are visited and removed. The vessels originating from the center of the abdomen in the suspensory ligaments of the intestinal segments (mesenteries) are visualized and set off very centrally, at the lower edge of the pancreas. This radically removes the entire drainage area of the lymph, including the lymphatic channels and the lymph nodes. This step is important in the case of tumor disease. The number of lymph nodes found and affected by the tumor is crucial for the future (prognosis) and for adequate treatment with chemotherapy. Subsequently, the rectum, which is located in the lesser pelvis, is mobilized, and the surgeon must be careful not to injure either ureter. The rectum lies within a suspensory band of surrounding fatty tissue (mesorectum), in which the vessels and lymphatic channels run.

The mesorectum is thoroughly removed to eliminate any metastases that may be present. This modern surgical method (TME, Total Mesorectal Excision) was introduced in 1985 by Professor Bill Heald. The tumor-bearing bowel section with the associated suspensory ligaments (mesenteries) and all possibly tumor-involved lymph vessels and lymph nodes are removed. The nervicavernosi, which are important for male potency and which run close to the place where the rectal part has to be removed, can practically always be preserved thanks to this technique. The next step is to restore the continuity of the intestine. The most modern stackers and stapling machines are used for this purpose. They allow anastomoses of the intestine even only a few centimeters from the anus, i.e. in places where sutures were not possible a few years ago and patients therefore had to live with an artificial anus praeter.

Today, less than one in five affected patients still needs an anus praeter. Finally, the patient is checked for blood dryness, a silicone drain is inserted, and the abdominal wall is closed in layers. Finally, two surgical measures should be mentioned, which find their application in very special situations. One is ileotransversostomy, which is performed for large, bowel-constricting tumors in the right colon. This involves “bypassing” the tumor, so to speak. The small intestine is sutured side to side with the part of the transverse colon located downstream of the tumor to allow unobstructed passage through the intestine.

Artificial bowel outlet – stoma

Another measure, which unfortunately is often not avoided in intestinal surgery but can become a severe psychological burden for the patient, is the creation of an artificial anus (anus praeter). It is used to drain stool and gas from a section of intestine outward through the abdominal wall into a bag. Depending on whether a small bowel or large bowel section is being passed out, it is referred to as an ileostomy or colostomy. Either a stoma can be created as a short-term measure with the aim of restoring bowel continuity after a few months by repositioning it, or it is a permanent expulsion.

The reasons that lead to the creation of a stoma vary:

– Impending intestinal obstruction due to a non-resectable tumor

– Inflammatory bowel disease

– To protect a diseased section of intestine until it is fully functional again.

If the surgeon has to create a stoma, he will prepare a sufficiently large opening of the abdominal wall at a suitable location. The intestinal stump is carefully pulled through this and carefully sutured in place. The intestinal opening located in the abdominal wall is then supplied with a special bag. Many patients feel a great deal of stress at first due to an ostomy. They no longer feel socially acceptable and are embarrassed, even though today’s disposable materials for stoma care are excellent and make patients feel safe.

Self-help group of stoma carriers

Stoma patients can sometimes the self-help group of stoma carriers (ilco Switzerland), which provides human and professional competent support to the affected patients. But also special care specialists, so-called stoma therapists, are able to be a helpful support for patients in their daily lives.

Ilco Switzerland is a non-profit organization. The umbrella organization with its 13 regional groups and the young ilco offers support, advice and guidance to stoma carriers and their relatives in collaboration with stoma therapists and medical care staff. To help each other, they share their experiences. They maintain contact at meetings, in discussion groups, at lectures and excursions, and answer questions that go beyond medical advice. The various tasks are carried out by specially trained ilco members working on a voluntary basis. Read more >

Even though medical care is good in this country, a stoma remains a limitation that is not always easy to live with. No one knows and feels as well as those affected themselves what they need for their well-being and how everyday problems can be solved. Therefore, patients who have just undergone surgery benefit particularly from the experience of long-term stoma patients. The self-help organization ilco Switzerland was born out of this consideration.

Laproscopic surgery

Advantages of laparoscopy include less postoperative pain, earlier mobilization, and more cosmetically favorable outcomes. Disadvantages include in the greater technical effort and the longer duration of the operation.

What happens after the treatment?

As a rule, the patient is cared for in the intensive care unit for one to two days after the surgery. All important laboratory values are checked, and adequate pain and infusion therapy is scheduled. Antibiotic administration is continued. Due to the intestinal anastomosis, the patient is not allowed to eat or drink for up to five days to prevent leakage in this area – a complication that is very complex to treat. After these days, the patient is allowed to drink a little again so that the intestines can resume their activity. This can be a rather painful phase for the patient, as the bowel is partially distended (paralysis) and often resumes its activity with cramps. Gradually, the food continues to build up via soup and pureed food. Read more >

In patients with more extensive tumors in the rectum, additional chemotherapy or radiotherapy must be discussed in consultation with the oncologists and radiation oncologists. This is because treatment with chemotherapeutic agents is often important prior to surgery to allow resection in the first place or to improve outcomes with combination therapy. In advanced tumors, this procedure is quite important today. Nevertheless, the most important therapy remains total mesorectal excision (TME) of the rectum by an experienced surgeon.

If the patient has a stoma, a special stoma advisor will familiarize him or her with the procedures and materials involved in stoma care. Depending on the size and type of tumor removed, each patient is followed up individually. Tumor markers are checked at certain intervals, and an ultrasound or CT scan of the abdomen and possibly a colonoscopy are performed to make sure that no metastases have occurred or that no new tumor has developed.

5. chronic inflammation in the intestine

Inflammation in the colon – ulcerative colitis

What is ulcerative colitis?

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Typically, it often progresses in relapses, with periods of disease alternating with symptom-free periods with episodes of inflammation. Ulcerative colitis affects only the colon and remains confined to the uppermost layer of the intestinal wall, namely the intestinal mucosa. There, “ulcers” form, i.e. wounds and shallow defects in the mucosa. The Latin term “ulcus” means “ulcer”, while “colitis” stands for inflammation of the large intestine (colon). This is where ulcerative colitis gets its name.

More about ulcerative colitis

Women are affected by the disease slightly more often than men. As a rule, this disease progresses in relapses, which means that patients may be symptom-free for years until the inflammation recurs. If the mucosa is examined during a disease episode, highly inflamed areas with severe “ulceration”, so-called ulcerations, are found. If the inflammation subsides, the healthy mucosa between the ulcerations reacts by overshooting cell formation, which then appears as mucosal growths (polyps). The “ulcers”, on the other hand, heal as a scar, which makes the intestinal wall rigid (like a tube) and non-functional. Read more >

For the surgical aspect of the disease, it is important to note, among other things, that the likelihood of developing colon cancer increases with increasing duration of disease (>10 years) and involvement of the entire colon, and in this context requires special surgical measures. After these brief explanations of this disease, the surgical measure in particular will be discussed here.

Exemplary for the spirit of optimism in abdominal surgery under these new conditions is the work of the surgeon Professor Ulrich Kroenlein, who worked and taught at the University Hospital Zurich since 1881. He translated the new hygiene ideas into measures in the hospital by having floors tiled, wooden bedsteads removed, and a new operating room built in the form of an amphitheater (student classroom). Kroenlein was one of the first surgeons to operate on acute appendicitis and was involved in the treatment of purulent peritonitis, a complication that occurs particularly after intestinal injuries.

In order to avoid such peritonitis caused by bad intestinal sutures (anastomosis), two other famous surgeons at that time were struggling to find new suturing techniques in intestinal surgery, Theodor Kocher and Vincenz Czerny. “Intestinal resection has become an extraordinarily important and relatively frequent surgical procedure, by the correct performance of which the surgeon can preserve many a life otherwise irrecoverably lost.” Writes Theodor Kocher in 1894, introducing his continuous intestinal suture (Boschung U.: Milestones in the history of intestinal anastomosis. Swiss Surg 2003; 9: 99-104). For example, as early as 1907, Sir Ernest Miles performed the first radical abdominoperineal resection for rectal carcinoma, a major procedure in which the colon and rectum were completely removed.

For the removal of the diverticulum-bearing portion of the sigmoid loop, the results were particularly good when preoperative lavage of the bowel, consistent antibiotic administration, and new suturing techniques were introduced with today’s modern suture materials. A major step towards low complication rates, short hospital stays and good postoperative results has been achieved by the recently introduced minimally invasive laparoscopic sigmoid resection. Together with the concept of “fast track” surgery (gentle, low impact surgery for patients), sigmoid resection for diverticular disease has now become a safe surgery with low complication rates.

Symptoms of inflammation of the intestine

Characteristic of ulcerative colitis is bloody mucous diarrhea that can occur up to 20 times per day. Pain and cramp-like discomfort occur in the area of the colon frame and rectum, as well as in the area of the sacrum. These episodes can be accompanied by a feeling of fullness, strong gas formation in the intestine, fever, an increase in inflammatory signs in the blood, and severe weight and protein loss.

The acute onset of the disease, as well as recurrent relapses, may be associated with certain complications, although rarely. Acute distension of the colon (toxic megacolon), significant bleeding in the area of ulceration, abscess formation, and/or rupture of the bowel wall may occur, and surgeon intervention may be urgently required.

Necessary clarifications and diagnostic possibilities

At the latest when a patient discovers blood and mucus in the stool, they should consult a doctor to have the necessary investigations carried out. The physician must first try to gather information regarding bleeding, weight loss, fever and pain via a detailed questioning of the patient and create the basis for further diagnostics. He must palpate the colonic frame for tenderness and digitally examine the patient’s rectum. Then a laboratory test should follow, which must primarily record important inflammatory parameters. Read more >

Colonoscopy with tissue sampling and bacteriology may help confirm the diagnosis, and an x-ray of the bowel with water-soluble contrast may show altered bowel wall structure. Because, no sign, no symptom on its own is conclusive for ulcerative colitis, only the synopsis of all examination results can yield the correct diagnosis, since there are also other inflammatory bowel diseases that cause similar complaints.

The acute onset of the disease, as well as recurrent relapses, may be associated with certain complications, although rarely. Acute distension of the colon (toxic megacolon), significant bleeding in the area of ulceration, abscess formation, and/or rupture of the bowel wall may occur, and surgeon intervention may be urgently required.

Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease

Treatment of an acute disease flare-up includes high-dose cortisone administration, special anti-inflammatory drugs, abstinence from food, and intravenous fluid administration. This medical treatment may be necessary for a very long time. However, here we would like to present the surgical procedure used when colon carcinoma has been additionally found in the setting of this disease or when consistent conservative therapy has failed. Read more >

The surgical treatment procedure is continence-preserving proctocolectomy with J-pouch placement. Patients with long-standing ulcerative colitis are regularly colonoscoped, as this condition is associated with an increased likelihood of developing carcinoma. If carcinoma is diagnosed, the entire colon must be removed because there is a risk that a tumor could also develop in another location over time. If the colon (including the rectum) is removed as a whole, as is done in a proctocolectomy, the patient lacks the part of the intestine that thickens the liquid food pulp, but also the rectal ampulla as a stool reservoir. The rectal ampulla and the anus, with its special musculature, are intricately coordinated and together form the anatomical unit that allows humans to have fecal continence. For many years, patients who had undergone proctocolectomy therefore had to be provided with an artificial small bowel outlet (ileostoma).

The ileostomy is used to drain stool and gas from a section of the small intestine through the abdominal wall into a pouch. In the meantime, however, there is a surgical procedure which aims to form a “stool reservoir” from a loop of small intestine (J-pouch), so that the patient can still defecate via the anus. This procedure assumes that the affected patient has no anal disease and the sphincter muscle is functioning well. Nevertheless, this operation is a major surgical procedure, and pouching has advantages and disadvantages that need to be explained very carefully in advance. This will be discussed again in the last chapter.

An open proctocolectomy requires a large incision from the breastbone to the pubic hairline. Then the abdominal wall is cut in layers until the abdominal cavity is opened. The surgeon first palpates all organs, such as the liver, spleen and stomach, by hand to see if there are enlarged lymph nodes and metastases. Then he looks for the ascending colon on the right side and the “caecum” and detaches both from the abdominal wall. The entire colon frame is subsequently mobilized. The transverse colon is carefully pushed off the peritoneum, the suspensory ligaments are cut from the transverse portion to the stomach, and the descending colon in the left lower abdomen is also detached from the peritoneum. In the area of the cecum, the small intestine is cut with a stapler. The blood vessels leading to the sections of the colon that will later be omitted are visualized and interrupted, and the colon is further mobilized to the sigmoid loop.

During this phase of the operation, the surgeon also repeatedly checks that the ureters on both sides remain uninjured. The rectum is carefully detached from the pelvic tissues as it progresses, almost to the anus. The surgeon now checks whether the length of the small intestine loop reaches the lowest section of the rectum so that the new reservoir can later be connected without tension. The surgery is now continued from the anus. Approximately one to two centimeters from the anus, the mucosa of the rectum is peeled off, but the muscular sheath of the rectum remains. The colon and rectum, which have already been mobilized, are placed at the point where the mucosa was exfoliated.

The reservoir (pouch) is then formed from the lower loops of small bowel by folding the end of the small bowel over in a J-shape and suturing the walls that touch each other in the process. Personally, I construct each pouch with single button seams so that the seam stretches well. I consider staple sewing equipment to be unsuitable here. Then the small bowel reservoir is gently pulled down towards the anus and sutured in the sphincter muscle area in the muscular layer and mucosal layer of the rectum. In the area of the tip of the J-shaped pouch, an opening of one and a half centimeters is cut and sutured to the layers of the anus rectum.

To initially relieve the anastomosis in front of the anus, the surgeon creates a temporary ileostomy in the area of the right lower abdomen. For this purpose, a small, round skin incision is made, the abdominal wall is carefully opened at this point, a piece of small intestine is pulled through this opening in front of the abdominal wall, the intestine is opened and finally sutured into the skin. The intestinal contents can then empty into a bag through this opening over the next few months, so that the newly created reservoir is still protected and all sutures can heal. A thorough check for blood dryness, insertion of two drains, and layer-by-layer closure of the abdominal wall is performed.

What happens after the treatment?

Each patient is initially monitored in the intensive care unit for one to two days. Important laboratory values are checked, comprehensive pain therapy is carried out, infusions are given in sufficient quantities and antibiotics are administered. This is important because the patient loses large amounts of fluid through his ileostomy, since the colon can no longer perform its thickening function. As a rule, however, these quantities regulate themselves downward in the coming period. The patient is mobilized and, with the help of stoma advisors, learns how to care for the artificial bowel outlet and insert the necessary accessories. Read more >

The ileostomy will relieve and protect the suture site in the rectum for two to three months. It is then repositioned in a further operation. During this procedure, the small intestine is carefully removed from the abdominal wall and mobilized The “stoma-bearing” portion of the small intestine is removed and rejoined. During this surgery, the surgeon will assess, from the anus, the suture site in the rectum and the condition of the reservoir, and make any corrections. After repositioning of the ileostomy, the patient will initially have frequent defecation via the reservoir (approximately 10 to 12 times per day). However, this high frequency usually reduces to four to six times per day after a few months.

At this point, it is necessary to mention a complication of pouchitis, which must always be mentioned and explained when considering performing such an operation: Pouchitis, a non-specific inflammation of the small intestinal reservoir, the cause of which is still not fully understood. Is it a bacterial infection? Is it the continuation of colitis in the small intestine? Or are there certain metabolic changes in the intestinal mucosa? About 40% of pouch wearers experience such reservoir inflammation once, some more than once. Antibiotic therapy is usually successful in combating this condition, although it is not known for certain whether bacteria are actually causing this inflammation. Only very rarely does this complication take a chronic course, ultimately requiring removal of the pouch. Half of the patients with pouching never experience inflammation in the reservoir or experience only very minimal inflammation, so it appears that individual factors may play a role in the development of such a complication.

Historical

As recently as 150 years ago, about two-thirds of patients undergoing hernia surgery died. Even in minor procedures such as finger and toe amputations, 10% of patients died. Reasons for this high mortality were the lack of anesthesia, antisepsis, and the problem of “shock.” This latter phenomenon is caused, for example, by high blood loss or by washed-in bacteria and can be fatal. But then groundbreaking discoveries were made that remain the firm foundation of any major abdominal procedure today. Read more >

In 1844, the first anesthesia with nitrous oxide was performed by Horace Wells, and in 1901, Karl Landsteiner discovered the blood groups of humans. This opened up the possibility for the first time to perform blood transfusions during major surgical operations and to successfully treat hemorrhage shock. The greatest achievement, however, was Ignatz Philipp Semmelweiss’ realization that wound infections, which were usually fatal at the time, especially puerperal fever, were caused by poor hygiene of hands and instruments. Until then, thorough hand disinfection was completely unknown in hospitals. One “carried”, without knowing it, the bacteria from one patient to another. Unfortunately, Semmelweiss was too far ahead of his time, so his appeals for hand disinfection with carbolic acid, despite proven efficacy by Luis Pasteur, the famous discoverer of the bacteria, were not taken seriously at first. It was the surgeon Joseph Lister in Glasgow who heard Semmelweiss’ ideas and successfully implemented them in his clinic in 1867: Before operations, the surgeons’ hands were washed with carbolic soap, and a carbolic solution was atomized over the surgical area during the operation. This significantly reduced the number of fatal complications after surgery.

In the course of this knowledge, operating rooms were then created that could only be entered with a hood and mouth guard, so that the first major abdominal surgical procedures, which were then also performed aseptically, were more successful from 1880. Exemplary for the “spirit of optimism” in abdominal surgery under these “new” conditions is the work of the surgeon Professor Ulrich Kroenlein, who worked and taught at the University Hospital Zurich since 1881. He translated the new “hygiene ideas” into measures in the hospital by having floors tiled, wooden bedsteads removed, and a new operating room built in the form of an amphitheater (student classroom). Kroenlein was one of the first surgeons to treat acute peritonitis and was involved in the treatment of purulent peritonitis following intestinal injuries.

To avoid such peritonitis caused by poor intestinal sutures (anastomoses), two other famous surgeons at that time were struggling to find new suturing techniques in intestinal surgery, Theodor Kocher and Vinzenz Czerny. “Intestinal resection has become an extraordinarily important and relatively frequent surgical procedure, by the correct performance of which the surgeon can preserve many a life otherwise irrecoverably lost,” wrote Theodor Kocher in 1894, introducing his continuous intestinal suture (Boschung U. Milestones in the history of intestinal anastomosis. Swiss Surg 2003; 9: 99-104). For example, as early as 1907, Sir Ernest Miles performed the first radical abdominoperineal resection for rectal carcinoma, a major procedure in which the colon and rectum were completely removed.

6. hemorrhoids

Dilated, twisted blood vessels in the wall of the lower rectum and anus

Vascular cushion at the exit of the terminal diaphragm