Extra Information

Warning

The diseases described on the following pages contain images and film material taken during operations. Decide for yourself if you want to see these images. Please also note our imprint and the legal information. The Baermed practice assumes no liability. Do you really want to see the page!

ESOPHAGUS

Topics

- Location and function of the esophagus

- Diseases of the esophagus

- Zenker’s diverticulum

- Esophageal Cancer

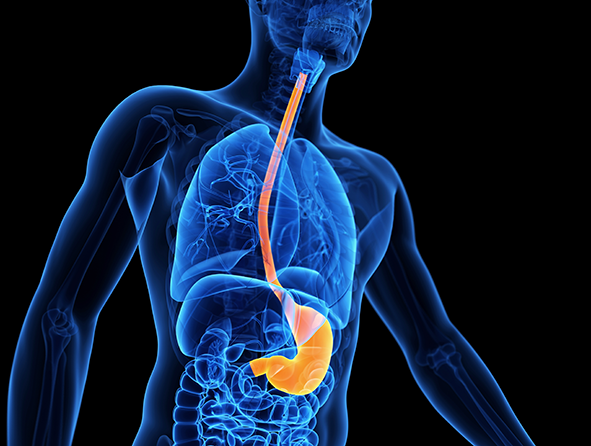

1. Position and function of the esophagus (estrophagus)

Part of the digestive tract

The esophagus is an approximately 25 cm and begins below the larynx. It runs behind the trachea and heart and ends at the stomach after passing through the diaphragm.

Where is the esophagus located?

The esophagus is a 25-centimeter-long muscular tube that connects the pharynx to the stomach. In the area of the larynx begins the upper part of the esophagus, which has an important sphincter at this point, since the backflow of food pulp upward must be prevented, because here is in close proximity to the entrance to the trachea. The areas of the sphincter muscles in the esophagus have a protective function on the one hand, and on the other hand they form a clear constriction due to the sometimes higher muscle pressure. Read more >

Continuing downward, the esophagus lies behind the trachea; this in turn is well protected behind the sternum. After about nine centimeters, the trachea, which lies in front of the esophagus, bifurcates into two main branches (bronchi), which flank the heart, which lies in front of it, on the left and right from behind. At this point, the main artery from the heart also passes over the left bronchus. The esophagus passes behind this site, which is also surgically challenging, in a straight line downward and enters the abdominal cavity after a total of 20 to 24 centimeters through a special opening in the diaphragm (hiatus).

Just before the esophagus passes into the stomach, there is again a sphincter located in the wall to prevent stomach acid from rising into the lower part of the esophagus. Because of this risk, this site is a critical transition zone of the esophagus, which is why the wall structure of the esophagus must also be explained.

The mucosa consists of an uncornified squamous epithelium that slowly merges into the cylindrical epithelium of the stomach in the lower part of the esophagus. If gastric juice flows permanently back into the lower esophagus, the mucosa in this zone becomes diseased (reflux disease), occasionally to such an extent that the squamous epithelium here changes to cylindrical epithelium and can thus become a kind of precursor to carcinoma.

In the next layer, the esophageal wall consists of transverse and longitudinal muscles, which ensures that the food pulp is transported onwards quickly. The esophagus lacks an outer, tight and smooth covering (serosa), as is also the case with the stomach and intestines, and causes the high demands that are placed on every suture in this area, as a further, strengthening layer of the wall is lost .

How does the esophagus work?

The swallowing process, in which the esophagus is involved, is subject to a very complicated neurogenic control. Swallowing triggers a peristaltic wave, and the upper and lower sphincters must relax sequentially at a specific interval to allow the food to pass. Outside the act of swallowing, the areas of sphincter muscles belong to a high-pressure zone, which ensure that food does not enter the trachea and that gastric acid rises back up into the lower esophagus. The latter phenomenon is the most common “closure disorder” of the lower sphincter and is due to a slackening of the muscles in this zone. It causes reflux disease, which, however, can be treated mainly with acid-inhibiting drugs.

2. Diseases of the esophagus

Most common diseases of the esophagus

Benign disease: diverticula

Benign diseases of the esophagus include bulges in the area of the esophagus wall, the so-called diverticula, which differ from one another in terms of their point of origin. They typically occur in front of the upper or lower sphincter muscle when swallowing causes abnormal pressure peaks in the esophagus due to functional disorders. Most commonly (70%), a wall protrusion is found anterior to the superior sphincter and is referred to as “Zenker’s diverticulum” or “cervical pulsation diverticulum.” Read more >

During swallowing, the upper sphincter muscle closes too early, causing acute overpressure, which over time leads to protrusion of the mucosa through a muscle gap. With nine new cases per year per 100,000 population, esophageal cancer is the most common surgical disease of the esophagus, affecting men five times more often than women. As a rule, these tumors originate from the squamous cells of the esophageal mucosa and arise in fifty percent of cases in the area of the middle third of the esophagus. The main risk factor for developing such a tumor is probably chronic alcohol and nicotine abuse.

There are also tumors that originate from the mucus-forming cells (adenocarcinomas). They occur predominantly in the transition area from the esophagus to the stomach, because they are based on long-term damage to the mucosa with preexisting acid reflux from the stomach.

How do I recognize diseases of the esophagus?

Both patients suffering from a Zenker’s diverticulum and patients with an esophageal tumor will initially primarily notice dysphagia or difficulty swallowing. These can take the form of a feeling of pressure behind the sternum, as if food is stuck in one place. Sometimes even the food that has already been swallowed rises back up into the oral cavity. Occasionally, patients also describe discomfort such as a stinging burning sensation when swallowing. Zenker’s diverticulum, in particular, can also cause coughing, hoarseness and severe bad breath. The diverticulum may also be palpable as a small, prallelastic tumor in the neck, usually on the left side.

Necessary clarifications and diagnostic possibilities

As soon as a patient notices dysphagia, he or she should seek specialist care, because various diseases of the esophagus can cause these complaints. For this reason, the doctor pays particular attention to the patient’s medical history, because a diagnosis can be made in three quarters of all cases simply by asking precise questions: Are the swallowing problems dependent on the consistency of the food? What is the time course of swallowing difficulties after food intake – intermittent, slowly increasing? What is the temporal relationship between food intake and food resurgence? Are there any pre-existing conditions such as reflux disease or stroke? Has the patient noticed severe weight loss? Read more >

This should be followed by a thorough inspection of the patient’s mouth and throat and palpation of the neck for enlarged lymph nodes or soft tissue changes. Depending on the suspected diagnosis, an endoscopy of the esophagus is performed and at the same time a tissue sample is taken in the area of conspicuous mucosal areas. In addition, especially in the case of diverticula, an X-ray examination of the esophagus with liquid contrast medium is performed, which can also show movement disorders of the esophageal wall.

If the disease is a tumor, it may be necessary to perform an additional CT or MRI scan to see its extent and location in the chest. A preliminary examination by an ear, nose, and throat specialist may also be necessary to check the functionality of an important nerve in the area of the larynx. Depending on the patient’s pre-existing conditions and age, ultrasound examinations of the heart and a pulmonary function test are also performed.

3. Zenker’s diverticulum

Treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum

In the case of a Zenker’s diverticulum, the indication for surgery is given, completely independent of how severe the patient’s symptoms are, because the complication rate is low. For the operation, the patient is placed in the supine position and covered so that the neck area is easily accessible on the left side. The skin incision is made longitudinally to the side and left of the larynx over a length of six centimeters.

Careful dissection is then performed until the left thyroid lobe can be mobilized and flipped up, and a very important nerve that runs here is clearly seen. Now the diverticulum is dissected, visualized and ablated and the esophagus is closed again at this point. Finally, a special muscle cutting is performed in the area of the upper sphincter of the esophagus, where the pressure peaks during the swallowing act, so that the resistance in this area decreases during swallowing and a recurrence of a diverticulum can be prevented.

4. Esophageal carcinoma

Treatment of esophageal carcinoma

Indication for surgery

The indication for surgery in esophageal carcinoma depends on the tumor stage on the one hand, and on its localization on the other. Since 50% of tumors arise in the middle third, it must always be carefully clarified which positional relationship a tumor has to the bronchial system, since this is in close proximity. There is therefore a risk that the tumor will grow into the bronchi or aorta.

Depending on the location of the carcinoma, therapy may vary:

Upper third before the gullet

Cooperation with ear, nose and throat physicians

Middle third

Combination of surgery through the chest and through the abdomen

Lower third

Operation only from the abdomen

Special case

Tumor of the lower third of the esophagus with spread to the stomach (cardia carcinoma)

Two surgery methods

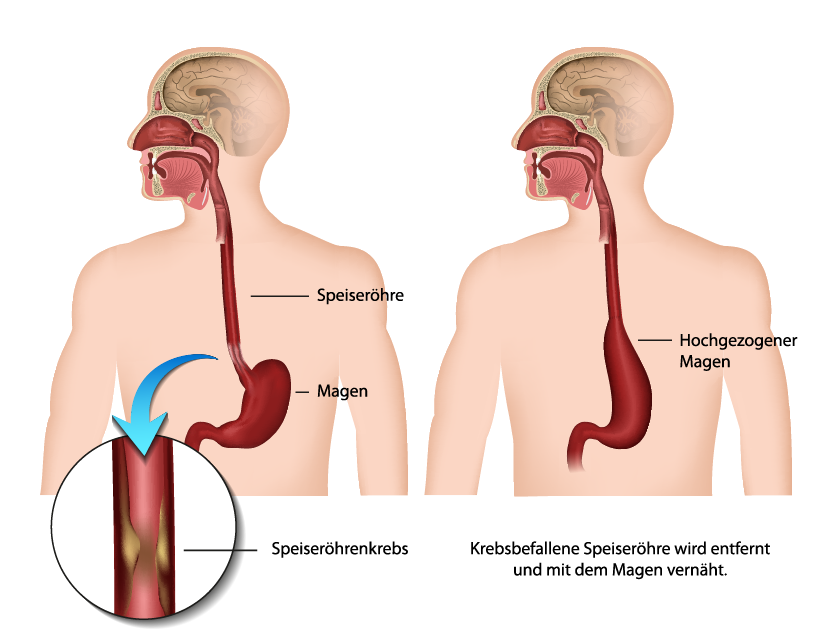

One-cavity resection and two-cavity surgery:

The basic difference is between a two-cavity operation (chest cavity and abdominal cavity) and a so-called “transhiatal esophagectomy” (single-cavity resection), in which only the abdominal cavity is opened and the esophagus is detached in the thorax bluntly, from the abdominal cavity. The upper end of the esophagus is then severed through an approach at the neck. Thus, the chest is not opened in this method. Read more >

a) Sinus resection (“transhiatal esophagectomy”)

Subtotal esophagectomy involves partial removal of the esophagus and gastric inlet, including major lymph nodes. This is always a two-cavity procedure, which means that the abdominal cavity and the chest must be opened.

b) Two cavity surgery

In two-cavity surgery, the patient is positioned on his back. The skin incision is first made from the lower end of the sternum to the navel. Then, layer by layer, the abdominal wall is cut and subsequently the opened abdominal cavity is carefully palpated by the surgeon’s hand. He pays attention to enlarged lymph nodes in the area of the aorta, to the surface of the liver and, if possible, to the extent of the tumor. Now the dissection and extensive mobilization of the stomach, lower esophageal segment and duodenum takes place.

In a second step, the chest is opened at the front right, running transversely about three transverse fingers below the areola, and the pleura is cut to expose the tumor in the area of the esophagus. After further dissection, the tumor including lymph nodes and surrounding fatty tissue is removed, which means that the esophagus above the tumor is also removed with sufficient safety margin. The tissue is examined by a pathologist while the operation is still in progress to see if the esophagus has settled in healthy tissue. Now follows the design of the gastric tube, which will later be pulled up into the chest to bridge the defect in the esophagus. To do this, the transition from the esophagus into the stomach is first removed over a length of about eight centimeters in the area of the entrance to the stomach using a cutting and suturing apparatus, so that a narrow tube is created here.

The stomach outlet (pylorus) is surgically widened as it becomes a constriction after unavoidable severing of an important nerve. The stomach inlet is placed in a plastic bag and later pulled up into the chest. To enable the new suture connection between the esophageal stump and the gastric tube, another skin incision is necessary in the area of the neck on the left side to provide the surgeon with the greatest possible overview. At this stage, the patient receives a thick gastric tube that is advanced through the nose and throat and ensures better splinting of the soft esophageal stump. The stump of the esophagus is marked with two strong holding sutures, which in the next step are pulled through the prepared gastric tube in the plastic sleeve and pull it up into the chest with manual assistance. There, the plastic cover is removed and the new stomach tube is given another opening in the area of the posterior wall so that the new suture connection (anastomosis) to the esophagus can be created here. This is finally sewn by hand in two rows.

Here, the most important suture is the suture of the esophageal mucosa, as only it is strong enough for anchoring the suture material. Finally, a drain is inserted in the area of the anastomosis and all skin incisions are closed layer by layer. It may be necessary to place a chest drain, as the lung may be injured on one side during surgery. The most important postoperative complication is leakage in the area of the new anastomosis between the esophagus and the new gastric tube. Therefore, the patient must abstain from eating and drinking for several days after the operation. Newer methods combine surgery with a minimally invasive procedure for the chest and a minimally invasive procedure for the abdomen, as well as suturing the neck. If the tumor spreads too far to the stomach, the stomach must also be removed, and part of the colon must serve as a stomach and esophagus replacement.

What happens after the treatment?

Often, a patient in the intensive care unit must continue to be ventilated for several hours after the end of surgery. As a rule, differentiated infusion and pain therapy is carried out in the intensive care unit, and laboratory values are checked regularly. Initially, the patient must not eat or drink anything for several days so as not to jeopardize the new suture connection. After about four days, the tightness of the suture may be checked by means of a contrast medium examination. After that, the patient may first drink sips of tea and broth. This is followed by a careful build-up of food via pureed food and finally a light whole food diet. Read more >

With the help of nutritional counseling, each patient learns while still in the hospital that he or she must first eat many small meals per day until the swallowing process works well via the new “esophageal passage.” Relatively late, when the surgeon is quite sure that the new suture is completely tight, the drain is pulled. Finally, the abdominal skin staples are removed on the tenth day. All patients can subsequently participate in a close-meshed follow-up program. The main aim of this is to detect the recurrence of the tumor at an early stage by regularly taking tissue samples. Collaboration between surgeons, oncologists and gastroenterologists remains very important.

As a late consequence of esophagectomy, a narrowing may develop in the area of the new suture, resulting in a disturbance of the food passage. To widen this constriction, if necessary, under sedation or anesthesia, gradual stretching of the tissue is performed using tapered rubber catheters of various sizes until good passage of the food is restored.

Historical

In the middle of the 18th century, the then world-famous surgeon Herman Boerhaave from Leiden was summoned on an emergency basis to the Grand Admiral of the Dutch Fleet. The latter was suffering from severe chest pains and was suddenly dying, apparently without any previous illness. Boerhaave first found out that the Grand Admiral had participated in a huge feeding frenzy the day before. In order to “relieve himself” after such a meal, as was customary at the time, he had eaten a little cinnamon. When this did not have the desired effect, he drank several cups of olive oil and beer. While trying to vomit, the Grand Admiral suddenly felt a racking pain in his chest and died some time later without the famous surgeon being able to help him. Read more >

Boerhaave, already a vigorous advocate of autopsy at that time – he always tried to prove the connection between a clinical symptom and the injury to an organ – was astonished by the findings: he found an esophagus that had a hole in the lower third through which the food had leaked into the chest. He dubbed it Boerhaave syndrome, a clinical term that sticks to this day Despite antibiotics and intensive care, this disease is still so severe that up to about 50% of affected patients die in the short term from complications without surgical intervention. The esophagus, which connects the pharynx and the stomach as a transport route for food, runs the entire length of the human thorax, which is actually the surgical field of cardiovascular and thoracic surgeons. However, in its anatomical structure and in terms of surgical techniques, the esophagus belongs to the digestive system, consequently in the hands of the abdominal surgeon. Nevertheless, it was initially predominantly thoracic surgeons who developed new techniques in esophageal surgery.

Franz Torek is considered a pioneer. In 1913, under primitive conditions from today’s perspective, he was the first to remove a tumor in the middle third of the esophagus. He successfully bridged the resulting defect with a rubber tube. He joined the esophagus and tube together in the upper portion and passed the whole out through the skin. He put the end of the tube back through the abdominal wall and sutured it to the stomach. Apart from the emergency solution with the rubber tube, essential features of the old surgical technique have been preserved to this day, except that today the defect is bridged with an elevated stomach or a special intermediate piece of small intestine or colon. As a rule, almost every operation on the esophagus is a “two-cavity procedure,” which means that the patient must have both the abdominal cavity and the chest opened to access the important structures.

Many technical details have been improved enormously, above all the suture material, the use of suture devices, but also sophisticated support from highly modern anesthesia and intensive care medicine, without which good results in this field could hardly be achieved today.