Extra Information

Warning

The diseases described on the following pages contain images and film material taken during operations. Decide for yourself if you want to see these images. Please also note our imprint and the legal information. The Baermed practice assumes no liability. Do you really want to see the page!

MAGEN

Topics

1. Location and function of the stomach

Part of the digestive tract

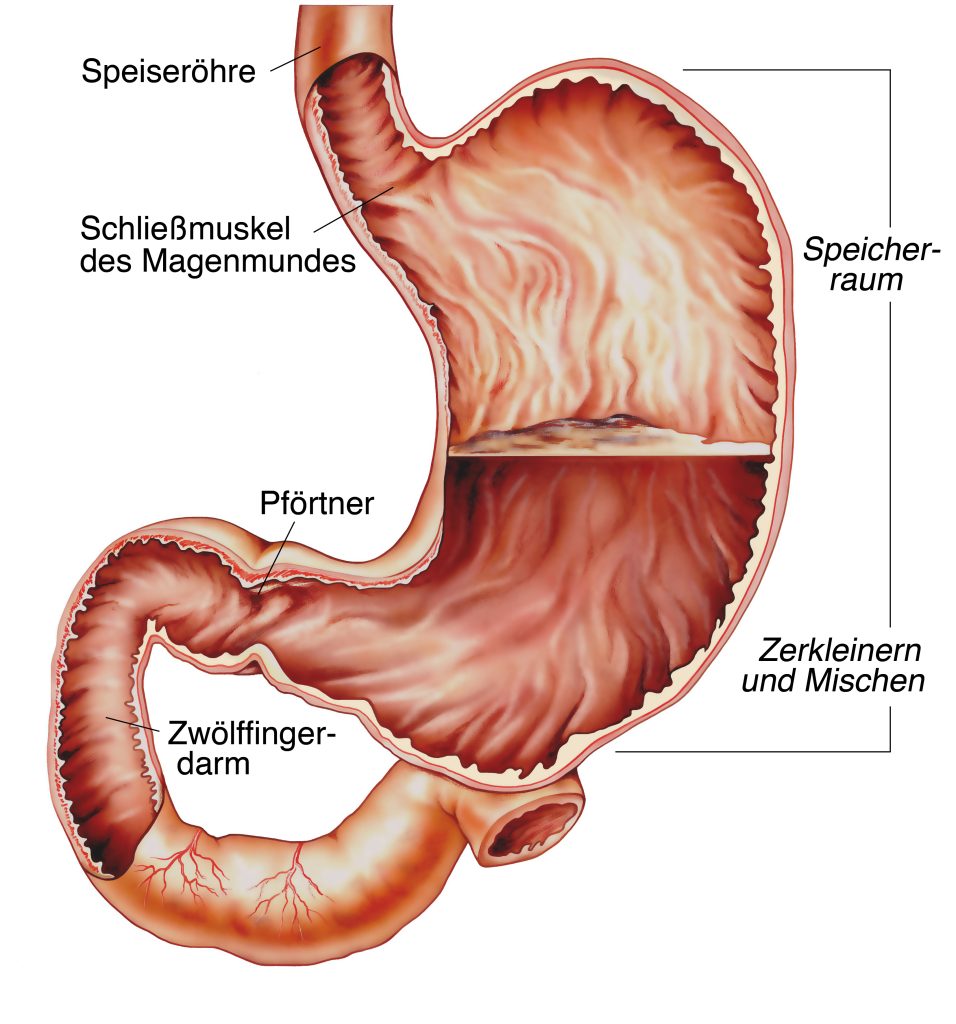

The stomach is a muscular hollow organ. Its task is to absorb food from the esophagus, mix it and decompose it. It then passes the predigested food pulp in small portions to the duodenum.

Where is the stomach?

In humans, the ingested food reaches the stomach via the mouth, pharynx and esophagus, which is located in the middle upper abdomen between the liver on the right side and the spleen on the left side. The transition from the esophagus to the entrance of the stomach lies approximately two to three centimeters below the diaphragm and was already called “cardia” in the time of Hippocrates.

This transition zone performs an important barrier function between the lower esophagus and the entrance to the stomach to prevent the backflow of food pulp and gastric acid into the esophagus. The stomach itself is roughly shaped like a bean, with the long side of the bulge facing the spleen on the left, the short side hugging the liver on the right, and the delicate pancreatic tissue covering it toward the back in the direction of the spine.

1 Liver

2 Stomach

3 Spleen

4 Pancreas

5 Large intestine

6 Small intestine

7 Gall bladder

The stomach segments

An extensive network of arterial vessels, some of them powerful, supplies the gastric tissue. The entrance of the stomach is followed by the actually largest part of this organ, the body (“corpus”) and the bottom (“fundus”). This is followed by the gastric outlet (“antrum”), which opens into the duodenum.

This transition point is called the “pylorus” or “gatekeeper”. The stomach itself is encased in a strong layer of ring muscle, which is responsible for the vigorous mixing of the food pulp. The innermost layer of the stomach wall is the gastric mucosa, which consists of a wide variety of cell types, each of which produces characteristic substances, especially gastric acid, which intervene in the chemical processing of the food or, for example, release mucus for natural “stomach protection”.

How does the stomach work?

The stomach is a storage organ in which the ingested food is broken down by chemical processing so that important substances such as fats, proteins, and sugars can subsequently be absorbed by the body in the duodenum through the addition of bile and pancreatic juice. The stomach produces about three liters of predominantly very acidic gastric secretions per day. This contains, among other things, pepsin and important hormones (gastrin and somatostatin) that act on the complex regulation of acid production. Our nervous system also has an influence on the release of acidic gastric juice from the corresponding cells: the vagus nerve is activated by smelling or tasting food, but also by stress factors and in turn triggers gastric acid release in the stomach. Other cells of the gastric mucosa continuously release mucus and thereby protect the mucosa from gastric acid. Read more >

Alcohol and coffee stimulate acid secretion in the stomach, but painkillers reduce the secretion of protective gastric mucus, so the balance of acid and mucus can be disturbed. The excess acid and/or the lack of mucus production, in addition to Helicobacter pylori, are causes of gastritis or peptic ulcers. Since 1982, it has been known that the bacterium Helicobacter pylori, which resides in the mucosa, plays a significant role in the development of gastric ulcers in more than one-third of patients with “gastric distress.” Meanwhile, there is also evidence that the presence of this bacterium significantly increases the risk of developing gastric cancer. Therefore, consistent therapy for gastroscopically proven peptic ulcers and bacteria present consists of both antibiotic and acid inhibitor therapy.

2. Stomach diseases

The most common diseases of the stomach

Most patients who consult a physician with significant stomach discomfort have chronic or acute gastritis triggered by poor diet, painkillers, alcohol, stress and/or bacterial colonization with Helicobacter pylori. After appropriate diagnostics (gastroscopy, bacteria detection) and initiated drug therapy, for example with acid inhibitors and antibiotics, gastritis is quickly curable and remains in the hands of the gastroenterologist.

If there is a deeper defect in the mucous membrane (ulcus), damage to blood vessels running in the stomach wall is possible, which can lead to life-threatening bleeding. Here, too, the focus is initially on conservative therapy, including gastroscopy and simultaneous hemostasis in the area of the defect, as well as the administration of acid inhibitors and antibiotics. In cancer death statistics, gastric carcinoma ranks fourth in humans. Although its occurrence in the lower third of the stomach has been declining significantly in recent years, carcinomas in the area of the gastric entrance are increasing. Read more >

The causes and risk factors of developing gastric carcinoma are discussed as follows: Familial accumulation of carcinoma, chronic gastritis and infection with Helicobacter pylori, and gastric acid deficiency. In most cases, the tissue type is a tumor derived from the glandular cells (adenocarcinoma), which would be correctly referred to medically as a primary malignant tumor of the stomach. If large enough, this tumor can give off metastases, which can further settle in the liver.

How do I recognize a stomach disease?

Usually, a patient with recurrent or persistent stomach pain, loss of appetite, heartburn, nausea, vomiting, or bloating will see a primary care physician. Symptoms can vary widely in severity, alone or in combination, and do not give the physician any clue as to the nature and severity of the disease. More than half of all patients with “stomach problems” have problems without organic causes. Nevertheless, other diseases must first be carefully excluded.

Necessary clarifications and diagnostic possibilities

Unfortunately, patients with acute gastritis, peptic ulcer, or gastric carcinoma often describe very similar symptoms. Careful questioning and examination by a specialist to make an accurate diagnosis is therefore essential. It is important to take an accurate medical history, including questions about family history, alcohol and nicotine habits, and the use of pain medications. Read more >

In order to make a diagnosis, it is also important for the doctor to find out whether there is a connection between the patient’s food intake and the development of pain or pain relief, whether the patient has lost a significant amount of weight or whether he has observed a reduction in performance. This should be followed by a thorough physical examination, including palpation of the abdomen to determine whether there is any enlargement of the organs or pain that can be triggered at specific points. A blood test is part of the basic diagnostics so that, for example, liver diseases can be excluded and possibly an expected anemia can be confirmed. Of course, if a patient has a bleeding peptic ulcer, he or she must be diagnosed and treated as an emergency. However, the basic principle of the procedure remains approximately the same: If indicated from the medical history, a gastroscopy is performed on the patient with

Locate the ulcer, inflamed mucosa, or source of bleeding, and remove tissue to detect Helicobacter pylori and/or tumor cells.

Rarely, an X-ray examination of the stomach with contrast media is additionally required. If there is a suspicion that a finding is gastric carcinoma, the diagnostics will be expanded, depending on the finding. CT, MRI, or ultrasonography of the abdomen will be necessary to evaluate the extent of the tumor, the lymph nodes, and the tissues of the liver.

How can gastric ulcer and gastric cancer be treated?

If bleeding is seen during a gastroscopy, regardless of whether it is diffuse mucosal damage or a punctate ulcer, the specialist will attempt to inject the bleeding mucosa with vasoconstrictive substances. At the same time, the patient is administered high doses of acid-inhibiting drugs via the vein. If bleeding nevertheless assumes threatening proportions or if a “hole” is found in the stomach wall in the area of the ulcer with a connection to the abdominal cavity, the patient must undergo emergency surgery.

The principle of the surgery (Billroth II gastric resection) consists in the removal of the lower two-thirds of the stomach, in which ulcers or simultaneous various mucosal defects occur most frequently. The surgery can be divided into two phases: Read more >

a) Removal of the lower two-thirds of the stomach with division of the connection to the duodenum

b) Side-to-side connection of a section of small intestine with the stomach stump.

After preparation and induction of anesthesia, access to the abdominal cavity is made through an incision that runs vertically from the lower end of the sternum to the umbilicus, still bypassing it on the left side if necessary. After severing the abdominal wall and appropriate dissection, the duodenum is separated from the stomach and closed blindly as a free end; however, it remains in its old anatomical position so that bile and pancreatic secretions can continue to flow into the duodenum in the area of the pancreas.

To ensure the good flow of the food pulp in the digestive system, a loop of small intestine following the duodenum is now pulled up in front of or behind the transverse colon, then opened and sutured side by side to the stomach stump. To allow secretions from the duodenum to drain easily, a “short circuit” is created between the duodenum and small intestine about 30 centimeters below the new stomach-small intestine connection.

A drain is placed in the area of the new intestine-stomach connection and drained to the outside through the abdominal wall. Finally, the abdominal wall is closed layer by layer. In the treatment of gastric carcinoma, surgical treatment is usually the primary option. Depending on the tumor extent and tumor location within the stomach, either only part or the entire stomach (total gastrectomy) is removed between the lower esophagus and the duodenum. All associated lymph nodes are also removed and examined. Whether this surgery also requires removal of the spleen, which is located close to the stomach on the left side, is determined by the location of the tumor in the stomach. Unless the carcinoma directly spreads to the spleen or its vessels, current evidence suggests that the spleen should not be removed. This extensive surgery requires thorough preparation, a thorough preliminary discussion with the anesthesiologist, and possibly additional cardiac and pulmonary testing.

3. Gastrectomy

The removal of the entire stomach

Stomach removal

A gastrectomy is the complete removal of the stomach during surgery. It is performed in cases of stomach cancer, among others.

The surgical procedure for total gastrectomy consists of two phases:

Phase 1:

Complete removal of the stomach and lymphatic drainage area

Phase 2:

Formation of a substitute stomach (Ulm stomach) from loops of small intestine

The abdominal cavity is accessed through a skin incision that runs from the sternum down to the belly button. The surgeon then cuts through all layers of the abdominal wall and carefully palpates the abdominal cavity by hand to assess the extent of the tumor and any metastasis to the lymph nodes and liver. The large mesh is detached from the transverse colon and folded back toward the stomach. The duodenum and stomach, including the lower part of the esophagus, are then dissected free so that in the subsequent step the stomach can be cut in the area of the esophagus but also at the stomach outlet (pylorus). Read more >

The right-sided gastric artery is severed just before it enters the main bile duct in the so-called “truncus coeliacus”, in the origin of the artery for the spleen, liver, pancreas, intestines and kidneys. In this area, all lymph nodes are removed. In this procedure, the compartments (regions) of lymph nodes and lymphoid tissues are radically cleared out and given for histological examination (frozen section) together with the removed stomach. Now comes the surgical phase: the formation of a replacement stomach. To do this, a piece of small intestine very close to the duodenum is dissected free over a length of 60 centimeters and cut through. The removed piece of small intestine is used as an interposition. At one end it is doubled over a length of ten centimeters. The intestinal walls, which now lie against each other, are opened and rejoined with the help of a special suturing technique in such a way that a new storage organ, the “replacement stomach”, is created here. The replacement stomach is opened at the apex and sutured to the esophagus. This is done either by hand, or occasionally with a special suturing apparatus.

The other end of the interposition is now sutured to the duodenum so that the food pulp can resume its usual path. Drains are placed in the area of the sutures between the esophagus and the replacement stomach as well as those to the duodenum, which drain the blood and wound fluid to the outside through the abdominal wall. The abdominal wall is closed again layer by layer, and the patient is subsequently transferred to the intensive care unit for monitoring. This somewhat more elaborate reconstruction is much better for later food buildup than a simple, so-called Y-Roux small bowel loop.

What happens after the treatment?

The patient remains in the intensive care unit for one to two days, where he receives balanced infusions and pain therapy. For the next five to six days, he must not eat or drink anything so that the fresh sutures between the esophagus and the small intestine and between the small intestine and the duodenum are not endangered, because a “leak” at these points means a serious complication in the healing process. Nevertheless, the patient should get up and move from the first day after surgery. If there is no indication that the new sutures are at risk, the patient may drink initially. If the intestines are working normally again at this point, i.e. the doctor can hear intestinal sounds through his stethoscope, a cautious diet build-up takes place under the expert guidance of the nutritionist. The drains are pulled out after costal buildup has begun, and the skin sutures or staples are removed on the tenth day.

What needs to be considered in the future everyday life?

Removal of larger portions of the stomach, but especially total gastrectomy, means deep surgery and a lasting change in the entire digestive processes of the gastrointestinal tract. As a result of the fact that the storage organ stomach has either been reduced in size or replaced by the small intestine, the ingested solid or liquid food now moves forward too quickly. Therefore, a number of symptoms may develop in the patient, which are summarized under the term “dumping syndrome”. These include diarrhea, nausea, sweating, hypoglycemia and tendency to collapse. Read more >

For example, if a meal is very high in sugar, the glucose may be absorbed too quickly into the bloodstream through the small intestine substitute stomach, causing a high insulin release, which in turn causes hypoglycemia in counter regulation. Or there may be a rapid influx of fluid into the intestine after food intake, which reduces circulating blood volume and may cause the patient to collapse. With the gastric interposition, this happens much less frequently, since the food passage is via the duodenum as usual. Important for patients is the help of nutritional counseling.

While still in the hospital, the patient must learn to eat many small meals per day and that these should be composed of specific foods. If the reservoir is enlarged after three to six months, it is often possible to eat normal food again. Every patient must be injected intravenously with one ampoule of vitamin B12 every six months, since the uptake of this vitamin for blood formation is linked to the so-called “intrinsic factor of the gastric mucosa”. If this factor is missing due to the removal of the stomach, there is a risk that anemia may develop. If the spleen had to be removed during surgery, the patient subsequently has a slightly increased risk of thrombosis, which can be reduced by taking aspirin 100 daily. In addition, he must be vaccinated against pneumococcal infections, as it is now known that patients are at increased risk of infection with encapsulated bacteria after splenectomy. In the case of carcinoma, further checks are carried out in collaboration with an oncologist.

Historical

In many idioms and proverbs of everyday life, the stomach seems to be an important organ: “This hits me in the stomach, this is heavy in my stomach, this turns my stomach”. Each of us knows life situations that can cause unpleasant feelings in the stomach area. Last but not least, we know that the consumption of cigarettes, coffee, fat, and numerous medications, coupled with enough stress, can lead to heartburn or a stomach ulcer. Read more >

Physicians already had this knowledge at the beginning of the 20th century, but the options for therapy were very limited: Patients had to keep to bed rest and were given a low-stimulus diet. Later, gastric acid was held responsible for the development of ulcers. The first acid blockade drugs were developed and used as standard therapy. Surprisingly, however, the rate of recurrent ulcers remained unchanged. It was not until 1982 that the physicians Robin Warren and Barry Marshall linked the bacterium Helicobacter pylori to the development of gastric ulcers.

Since 1996, the bacterium has been removed from the stomach lining by administering three drugs, with two different antibiotics and an acid inhibitor given to the patient. It is now scientifically proven that Helicobacter pylori is significantly involved in the development of gastric ulcers and mucosal inflammation. In addition, there is evidence that the presence of the bacterium increases the risk of developing gastric cancer.

The surgical procedures required for bleeding complications from ulcers or carcinomas were first developed and performed in Vienna in 1874 by one of the most prominent surgeons of the 19th century, Theodor Billroth. The conditions for this were good. He adopted from Joseph Lister the methods of sterilization and antisepsis. The anesthetic procedures with alcohol, chloroform, and ether already had their permanent place in the operating room. Billroth was the founder of gastrointestinal surgery and those new surgical techniques that are still standard procedures for abdominal surgeons today.

Theodor Billroth’s innovative procedures and techniques of partial stomach removal and end-to-end union with the small intestine opened up entirely new surgical fields and healing opportunities for patients at that time. Unfortunately, a well-known contemporary of Billroth, Theodor Storm, was no longer able to benefit from these advances: The work on his famous novella “Der Schimmelreiter” was overshadowed by his illness with stomach cancer.