Extra Information

Warning

The diseases described on the following pages contain images and film material taken during operations. Decide for yourself if you want to see these images. Please also note our imprint and the legal information. The Baermed practice assumes no liability. Do you really want to see the page!

PANCREAS

Topics

1. Location and function of the pancreas

Inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis)

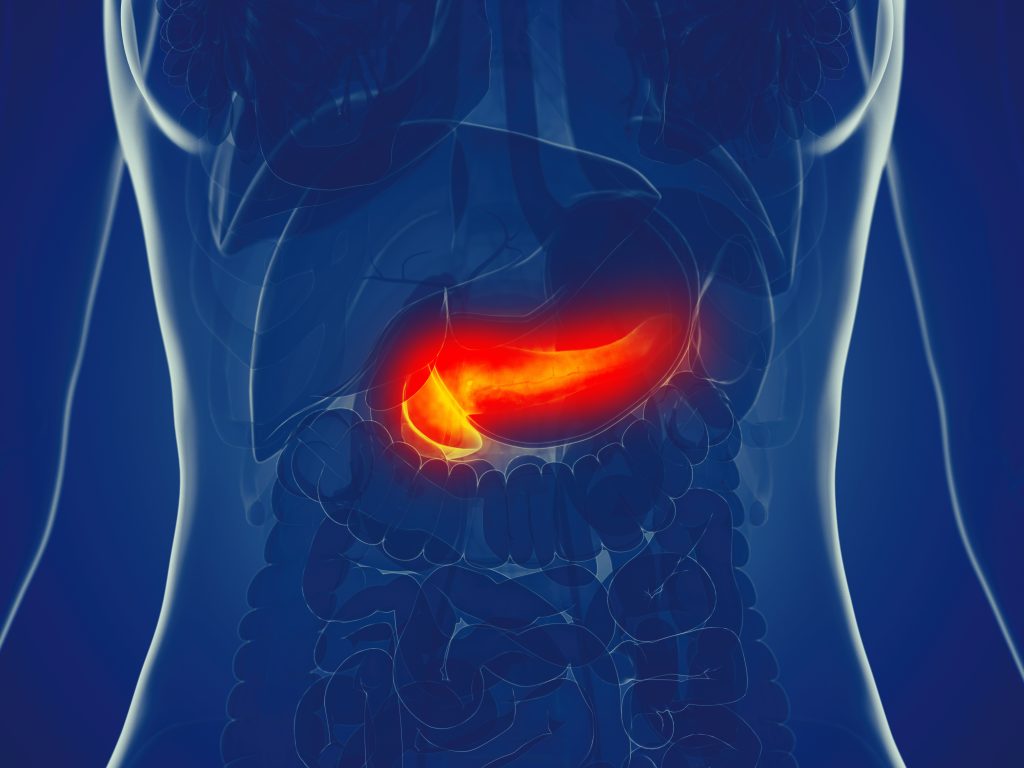

The pancreas is a glandular organ in the upper abdomen that is important for digestion and blood sugar regulation.

Where is the pancreas located?

The pancreas is a 15-centimeter-long, slender and delicate glandular organ that lies across the upper abdomen and resembles a walking stick with a thick handle. Taking the spine as the center of the body, the thick handle (pancreatic head) is located to the right of and in front of the spine. The pancreatic body moves to the left, past the spine, and crosses over into the pancreatic tail. Fortunately, this delicate organ lies, as if embedded in a thick “sandwich”, in our upper abdomen. Read more >

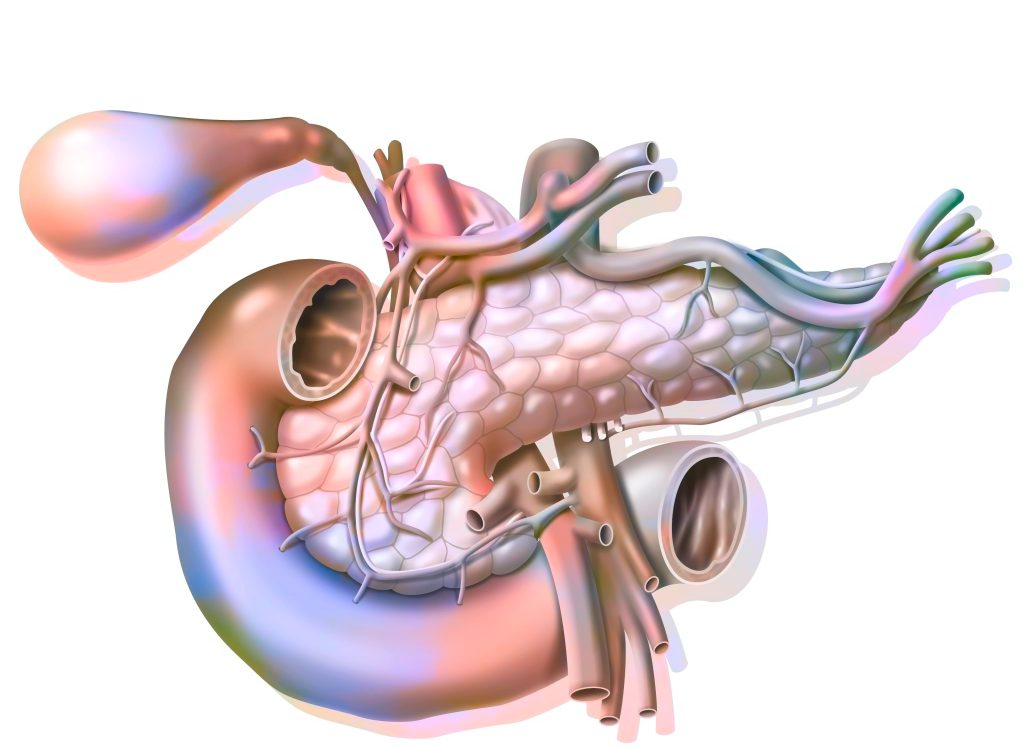

At the very back lies the bony spine; on this the large blood vessels (arteries and veins) run along this and cross under the head of the pancreas. The pancreas is covered in front by the stomach, on the right the pancreas head by the duodenum and on the left the pancreas tail by the spleen. The pancreatic tissue itself is formed from many small delicate lobules, which in turn are composed of glandular cells. Their outlets collect and eventually empty into the main duct, the ductus Wirsungianus, which passes horizontally through the pancreas and, together with the large bile duct, ends in the duodenum.

How does the pancreas work?

This highly complex organ could well be compared to a “chemical factory” that produces seven different substances (hormones and enzymes) with two different types of glands. The largest part of the tissue consists of the glands that produce a lye-like digestive juice (1.5 liters per day). This juice contains enzymes and flows into the duodenum via the ductus Wirsungianus to break down the ingested food into fats, proteins and carbohydrates. Scattered throughout this tissue is the other type of gland, the islets of Langerhans, which produce the vital hormone insulin, which regulates our blood sugar levels.

Therefore, in case of a serious disease of the pancreas with disturbed glandular activity, the patient may experience the following symptoms:

Digestive juice missing

The digestive juice is missing, thus vitamin deficiency, weight loss and fatty stools occur, because the ingested food can no longer be broken down.

Less insulin production

Less insulin is produced, blood glucose levels can no longer be adequately regulated, and the patient enters a diabetic metabolic state.

Chronic pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas)

The most common disease of the pancreas is acute inflammation (pancreatitis). It can lead to a life-threatening condition that is primarily treated with conservative medical care. However, complications of inflammation and especially chronic pancreatitis are treated surgically.

Pancreatic cancer (pancreatic carcinoma)

The exact causes of pancreatic cancer are still largely unknown today. There is speculation that there is a genetic reason for developing such a tumor, however, smoking and high-fat and high-protein diets are also considered risk factors. The main importance is given to the carcinoma of the glandular excretory duct.

2. Pancreatic cancer

Symptoms and surgery for pancreatic tumor

Where does pancreatic cancer occur?

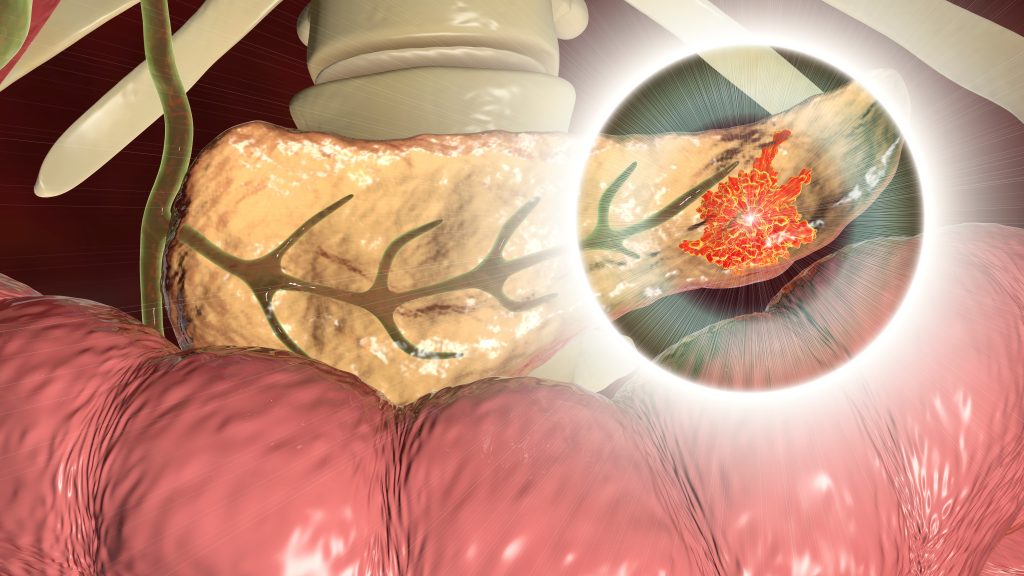

The exact causes of pancreatic cancer are still largely unknown today. There is speculation that there is a genetic reason for developing such a tumor, however, smoking and high-fat and high-protein diets are also considered risk factors. The main importance is given to the carcinoma of the glandular excretory duct. It arises from its mucosal cells and accounts for 80% of pancreatic tumors.

The majority of carcinomas are found in the head of the pancreas.

Rarely, but very important for the course of the disease, malignant tumors are found that originate from the islet cells, or so-called neuroendocrine tumors, which consist of a mixture of hormone-producing cells. Finally, it is important to mention carcinomas that originate from the papilla, the common inlet duct of the bile duct and pancreatic duct into the duodenum, and arise, so to speak, in the “border area” of the pancreas, bile ducts and duodenum.

Symptoms and diagnosis of malignant disease of the pancreas

Unfortunately, pancreatic cancer causes few and very uncharacteristic symptoms. This is because the pancreas is deeply embedded between other organs, so that the tumor cannot be palpated and therefore the disease is often quite advanced when it is diagnosed. Most often, patients observe non-specific symptoms that can occur in many gastrointestinal diseases: Bloating, nausea, food intolerance, fatigue and weight loss. Occasionally, uncharacteristic pain in the upper abdomen, which can radiate to the back, provides somewhat more evidence of the disease. If the tumor is located in the head of the pancreas, the mass may also obstruct the common bile duct and disrupt the bile flow. Bile contains bile pigments, which spill over into the blood when it builds up. Read more >

This leads to itchy skin, yellowing of the eyes, light-colored stools and dark urine. Unfortunately, there are no investigations, examinations or imaging procedures for this disease that can confirm or exclude the tumor with certainty. Thus, the physician must differentiate pancreatic carcinoma from chronic pancreatitis and from other gastrointestinal diseases by means of precise questioning of the patient and performing further diagnostics. These include questions about dietary habits, alcohol consumption, weight loss, and upper abdominal pain.

The physical examination primarily involves palpation of the upper abdomen with an evaluation of the gallbladder and liver. Sometimes a severely enlarged but painless gallbladder can be palpated. This is known as the Courvoisier sign, which can indicate the presence of a tumor. Laboratory tests will be used to record pancreatic and biliary levels and to determine the tumor markers CEA and CA 19-9. They are increased in the advanced stages of the disease, but unfortunately, not only characteristic of this tumor. Certainly the doctor will do an ultrasound of the upper abdomen.

This can be used to see masses or lesions in the area of the pancreas and to assess dilated or obstructed bile ducts and pancreatic ducts, as well as changes in liver tissue. After that, further diagnostics will be done on a completely individual basis. A CT scan or MRI can easily detect pancreatic tumors one centimeter or larger in size and show lymph node changes as well as growth that extends beyond the organ. If papillary tumors (confluence of pancreatic and biliary ducts) are suspected, endoscopic methods (ERCP) will be used to assess outflow obstruction, visualize ducts, and obtain tissue samples (brush cytology).

How is pancreatic cancer treated?

If the diagnostic procedures confirm a carcinoma of the pancreas or if they give rise to an urgent suspicion without any indication of derivatives (metastases), the tumor is surgically removed in operable patients. In the case of any well-founded suspicion of the presence of a carcinoma, the findings must first be verified by a tissue sample as part of a surgery. If the result is positive, the appropriate surgery must be performed. If tumor derivatives have already been found during the diagnostic procedures, it will not be possible to remove the tumor itself, but it may be necessary to surgically create a new drainage possibility for the stomach and bile ducts into the small intestine. If the tumor is already at an advanced stage, chemotherapy can be used to slow down its growth. Read more >

The classic surgical treatment option for an operable tumor in the head consists of the duodenopancreatectomy according to Kausch Whipple: the head of the pancreas, the pylorus, the duodenum, the bile ducts and the gallbladder are radically removed and the drainage channels via the small intestine are restored. For many years, this operation was considered very dangerous and not very successful. Today, advances in surgery, modern anesthesia procedures, and excellent as well as forward-thinking intensive care and critical care medicine have led to good surgical outcomes. Also, today it seems that the state of health after such surgery is satisfactory and rather superior to the non-surgical procedures. The indication and execution of this technically difficult operation belongs in the hands of a very experienced and highly specialized surgeon and should be discussed in detail with the patient, with specialists in gastroenterology and oncology, and with the general practitioner.

Surgical sequence

The pancreas is accessed through a transverse upper abdominal incision or longitudinal incision (Fig.3).

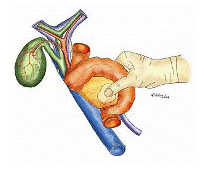

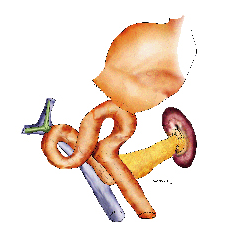

The head of the pancreas and the adjacent duodenum are dissected free (Fig. 4).

At the inferior border of the pancreas, the portal vein (large vein supplying blood from the intestines to the liver) is located and dissected completely free behind the neck of the pancreas (Fig. 5).

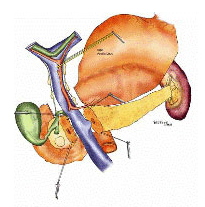

The common bile duct is cut, the gallbladder is dissected out of the liver bed, and all lymph nodes between the hepatic hilus and the head of the pancreas are removed. The neck of the pancreas is cut. (Fig. 6) Depending on the location of the tumor, part of the stomach may also need to be removed.

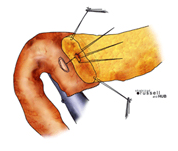

Reconstruction involves suturing a portion of the small intestine to the bile ducts, pancreatic duct, and stomach. Suturing the small intestine to the pancreatic interface is particularly difficult (Fig. 7; Fig. 8).

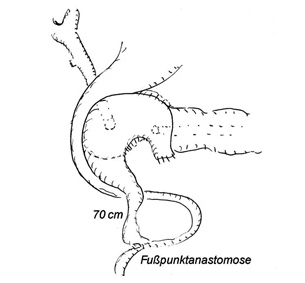

Reconstruction is performed with a small bowel omega snare (Fig. 9) if the stomach is partially resected, and with a simple small bowel snare (Fig. 10) if the gastric outlet is preserved.

Pancreatic left resection

Pancreatic left resection is another procedure. Here, the pancreatic body and tail are removed, but the pancreatic head is retained. Often, due to the narrow anatomical conditions, the spleen must also be removed, as it is tightly attached to the pancreas tail on the left side. In the case of carcinoma that grows diffusely throughout the pancreas, total pancreatic resection may be necessary as part of a Whipple procedure.

This operation has great consequences for the patient, who suffers a total loss of insulin and digestive enzymes due to the loss of all pancreatic tissue, which must then be replaced immediately. As a non-surgical therapy, be it for inoperative

What happens after the operation?

As after any major abdominal surgery, patients are treated in the intensive care unit for two to three days. The monitoring of respiration, circulation and urine output as well as the administration of painkillers and infusions take place around the clock. After surgery, antibiotics and a special drug to inhibit digestive juices (somatostatin) are given for seven days. Read more >

After leakage control, an amylase determination from the abdominal secretion of the drains, these are removed after four days, and the food build-up is started cautiously, with the gastric tube in place, when intestinal noises are already audible at the same time. Some blood values are also closely monitored, such as lipases, amylases and blood glucose, which may need to be controlled with additionally administered insulin.

Some patients may experience temporary gastric emptying disorders. Over the next few days, an assessment can then be made of the extent to which pancreas function is impaired and whether replacement of digestive enzymes and administration of insulin will be necessary over the long term.

Today, it is undisputed that a total removal of the malignant tissue should be followed by a subsequent treatment with chemotherapy in order to prevent the recurrence of the disease or to delay it as long as possible.

What must be paid attention to in everyday life?

All patients who have had pancreatic tissue removed must have close monitoring of their pancreas levels and blood glucose. Depending on whether fatty stools and diarrhea occur due to missing pancreatic enzymes, these missing enzymes are replaced with the appropriate medications. At the same time, the patient will receive nutritional advice in order to be able to keep to a balanced diet with little fat and protein. If high blood glucose levels occur, they are corrected by insulin.

Ongoing contact between the responsible primary care physician, oncologist, and surgeon is part of a patient’s routine follow-up. In recent years, new research findings, improved early detection, and new surgical techniques have significantly improved patient survival after pancreatic resection. Read more >

Nevertheless, the prognosis of these tumors is still very serious, as often, despite removal of the tumor, small portions of it must be left in the body. This has led many doctors to believe that the surgery is not promising. Nevertheless, we consider the notification of a surgery to be useful, because on the one hand it is often only through surgical treatment that the diagnosis can be definitively established at all, and on the other hand it is also often only during the operation that it becomes clear whether a tumor can be removed or not.

Therefore, strong research efforts worldwide are mainly focused on improved methods in early detection, but also on new therapeutic options to be able to improve the prognosis of this tumor in the coming years.

Historical

Alexandria around 300 B.C.: In their heyday, the Ptolemaic kings built a large university and library to allow scientists, artists and writers to research and teach. Here also worked the physician and anatomist Herophilus of Chalcedon, since at this university it was allowed to perform anatomical studies on cadavers, an activity that was strictly forbidden in other countries. The first more detailed descriptions of the pancreas and liver came from him. Read more >

Johann Georg Wirsung, professor of anatomy in Padua, discovered the large excretory duct of the pancreas in 1642, which is still named after him today: Ductus Wirsungianus. “But (…)”, he wrote to his teacher Jean Riolan, not knowing what he had actually found, “(…) should I call it artery or vein? I never found blood in it, but I did find a cloudy juice that acted on the silver probe like a corrosive liquid (…)”. The story came to a bloody end: a year after his discovery, Wirsungianus was murdered on his doorstep by a student. Was there a dispute about who had been the actual discoverer of the passage?

In 1869, Paul Langerhans, a medical student of only 22 years of age, came across the islet cells of the pancreas as part of his doctoral thesis, but did not know what function they had. About twenty years later, Oskar Minkowski and Joseph Freiherr von Mering removed the pancreas from a dog to observe the effects on sugar metabolism. The dog developed all the symptoms of diabetes, and the two researchers were able to detect glucose and acetone in the urine. This proved the connection between a malfunction of the pancreas and a subsequent development of diabetes. After Frederick Grant Banting and Charles Best discovered the substance produced by the islet cells, insulin, around 1920, it took only three years before the first insulin preparation to appear on the market – saving thousands of diabetics patients, for whom there was no hope before

The great surgeons of the time still considered the pancreas to be an “surgeon-hostile organ” with regard to its anatomical location and its its inherently fragile tissue. The surgeries were extremely surgically challenging and high risk for the patient. But the surgeon Carl Gussenbauer, successor of Theodor Billroth in Vienna, was an innovative mind. He had already developed the first artificial larynx as an assistant and was not deterred by such a delicate situation as that of the pancreatic pseudocyst, a complication of chronic pancreatitis. He found a procedure that allowed the fluid to be drained from these cysts.

In 1909, Walter Kausch broke new ground in Berlin by performing the first radical pancreatectomy, which always included removal of parts of the stomach and duodenum. In the 1930s, Allen O. Whipple revisited this technique for removal of a pancreatic tumor, but performed it in two separate procedures because of the high surgical risk. Since then, the “Whipple-Kausch” has been further perfected by many great surgeons and at the same time the procedure has become a standard procedure that is also very safe for the patient.

3. Pancreatitis

Symptoms and surgery for pancreatitis

The chronic inflammation as the most common disease

The most common disease of the pancreas is acute inflammation (pancreatitis). It can lead to a life-threatening condition that is primarily treated with conservatively However, complications of inflammation and especially chronic pancreatitis are treated surgically. Chronic pancreatitis is characterized by episodic, recurrent inflammation of the organ, usually in the area of the pancreatic head. Repeated inflammation causes long-term damage to pancreatic tissue, breaking it down and replacing it with scar tissue and calcifications.

The main cause of chronic pancreatitis is increased alcohol consumption over several years, gallstone disease of the bile ducts, trauma or genetic defect. In a proportion of patients, the cause remains unknown. The above-mentioned function of the pancreas also results in some of the (late) complications of this disease: digestive disorders in the form of fatty stools, diarrhea or constipation, bile outflow obstruction, blood sugar derailments, defective healing of the tissue in the form of large cysts (pancreatic pseudocysts) and abscesses, vascular occlusion of the neighboring arteries and veins, and, the worst of all for the patient is chronic upper abdominal pain.

Symptoms of pancreatitis

Unfortunately, the complaints with which affected patients consult a doctor are vary greatly. Why is that? A leading symptom of this disease is pain that radiates specifically from the upper abdomen to the shoulder or lumbar vertebrae. As a result, those affected often consult an orthopedist first. The pain attacks are initially limited in time, but as the disease progresses, they occur increasingly frequently and for longer periods of time, until they cease again when the inflammation is “burnt out”. Read more >

Patients are also often the first to complain of nausea and vomiting, food intolerance and bloating, without pain. Thus, the physician must differentiate chronic pancreatitis from other gastrointestinal diseases by questioning the patient in detail. These include questions about dietary habits, alcohol consumption, weight loss, and upper abdominal pain. It is important that the patient describes his/her pain, its frequency, intensity and localization as precisely as possible.

The physical examination primarily involves palpation of the upper abdomen with an evaluation of the gallbladder and liver. Furthermore, the color of the skin must be assessed (yellowing with bile stasis). The next step in the examination will be a blood test, in which the levels of the two most important pancreatic substances (lipase and amylase) will be determined. Furthermore, the blood sugar value and certain liver values are of interest in order to rule out bile stasis. Finally, imaging techniques are used to confirm the diagnosis. The ultrasound of the abdomen gives the physician a good orientation regarding all organs in the upper abdomen. At the same time, calcifications in the area of the pancreas can be easily detected and provide an initial indication of the disease.

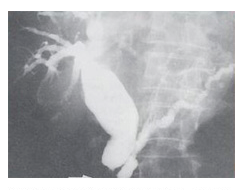

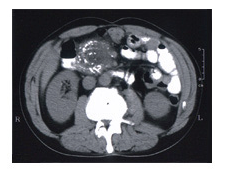

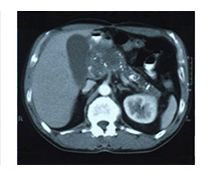

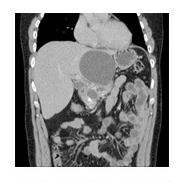

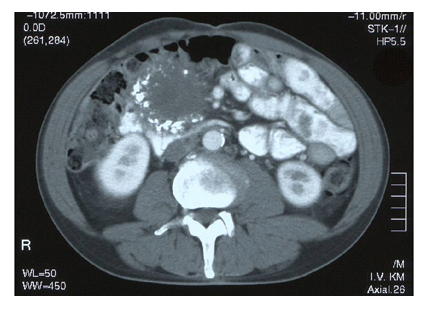

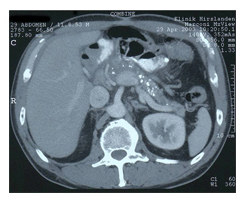

However, the exact assessment of the size and condition of the pancreas can only be made on the basis of a CT scan of the abdomen (Figs. 2a, 2b and 3). If necessary, an ERCP scan will attempt to visualize the common bile duct and the main pancreatic duct. This complex and precise diagnosis is made in order to be sure that there is “only” a chronic inflammation in the pancreas and that a tumor is not behind the symptoms.

Treatment and surgery of the pancreas

The treatment of chronic pancreatitis is based on two therapeutic pillars: The first priority is always conservative therapy with a wide various medications and a diet, followed by surgical procedures if the patient’s pain situation cannot be improved. Conservative therapy includes absolute abstinence from alcohol, a balanced diet with limitation of the amount of fat (possibly also a diabetes diet), replacement of digestive enzymes and taking a drug to inhibit gastric acid production. Read more >

In some patients, the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K may need to be replaced via intravenous administration. However, the main focus of conservative therapy is individually adapted pain therapy with centrally and/or peripherally acting analgesics (Morphine/Panadol). For many years, the increase in pressure in the pancreatic duct as well as calcification of the tissue were held responsible for the pain in chronic pancreatitis, whereas more recent studies also show changes in local nerve components. If these measures are not effective against the pain, ERCP examination will be used as interventional therapy. Interventional means an intervention that lies between conservative and surgical therapy. This involves the endoscopically controlled dilatation of the pancreatic duct and/or the bile duct, possibly with the insertion of a small tube (stent) to improve the drainage of the bile and the digestive juices

Surgical procedures are only used when pain cannot be relieved conservatively, the pancreatic duct is significantly obstructed, or bile and digestive juice cannot drain into the duodenum due to an enlarged pancreatic head. The previously mentioned complications of chronic pancreatitis, such as pseudocysts, abscesses, and hemorrhage, are also requires surgical therapy. Generally, a distinction is made between draining procedures and cutting away (resecting) procedures, with the surgeon’s goal always being to preserve as much pancreatic tissue as possible so as not to further limit glandular function. All surgeries explicitly belong in the hands of a highly specialized surgeon, as excellent planning, “high-tech” materials, and above all a great deal of surgical experience are required. The difficulty lies in suturing different types of tissue together, for example, suturing together pancreatic tissue and small intestine tissue: try to sew a piece of smooth silk with thread to a piece of soft butter. This example is relatively close to the surgical challenge.

During drainage, the congested and enlarged duct of the pancreas is “only” drained into the small intestine, but the chronically inflamed tissue of the pancreatic head is left in place. The procedure is called pancreaticojejunostomy (small bowel section).

Resecting procedures

The resecting procedures are divided as follows:

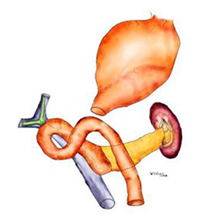

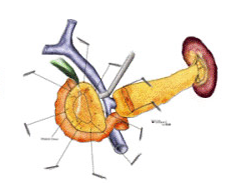

a) The classic duodenopancreatectomy (Whipple-Kausch surgery) (Fig. 4).

The pancreatic head, gastric outlet, duodenum, bile ducts, and gallbladder are removed, and the outflow tract is restored via the small intestine. For many years, this surgery was considered very dangerous and not very successful. Today, major advances in surgery, modern anesthetic procedures, intensive care and intensive care medicine have led to good surgical outcomes. The surgical procedure is briefly described here: Access is through a transverse upper abdominal incision or longitudinal incision. Read more >

The head of the pancreas and the adjacent duodenum are exposed. At the lower edge of the pancreas, the portal vein (large vein supplying blood from the intestines to the liver) is located and completely dissected free behind the neck of the pancreas. Subsequently, the main bile duct is cut, the gallbladder is removed, and the neck of the pancreas is detached.

The entire head of the pancreas is detached from adhesions against the posterior portion of the abdomen (retroperitoneum), and the duodenum is transected. In a further phase, part of the small intestine is sutured to the neck of the pancreas, the bile duct is sutured in about 15 cm away, and finally the stomach stump is connected to the small intestine.

b) The duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (operation according to Beger)

The procedure involves removal of the predominantly inflamed pancreatic head, but spares the stomach and duodenum, which are closely adjacent here, so that food passage remains undisturbed. The outflow pathways of bile and pancreas are restored via the small intestine. After completion of both surgical procedures, drains are placed in the area of important junctions to drain wound fluid to the outside (Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9).

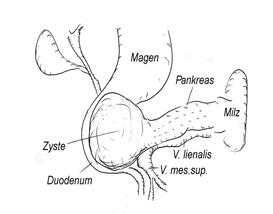

The duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (modified according to Büchler).

The advantages of duodenum-preserving surgery are bought with a technically difficult operation with transection of the pancreatic neck in findings where the pancreatic tissue is very strongly intergrown with the protal vein and dissection sometimes becomes practically impossible. The Büchler modification preserves all the advantages of head resection with removal of chronic inflammatory tissue without the disadvantages of pancreatic neck transection. Fig. 10 shows disease with a large cyst in the head of the pancreas with extensive calcifications as a sign of chronic pancreatitis.

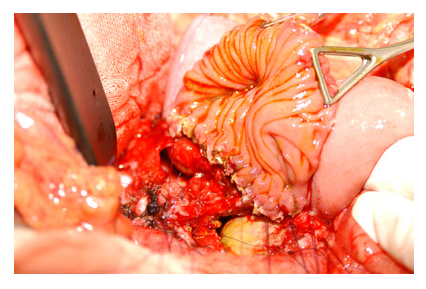

The large cyst in the head and tissue changes lead to chronic pain due to compression of the pancreatic duct and inflammation in the pancreatic head. This pain is virtually unmanageable with normal analgesics (Fig. 11).

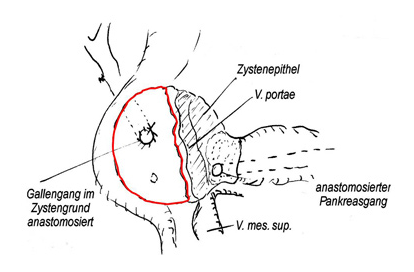

The surgery is performed to remove all inflammatory and scar tissue that causes pain. The portal vein is not dissected out, but again all tissue is removed down to the vein. The duct of the biliary tract is opened and drained within the, and the duct of the pancreatic body is also opened and drained (Fig. 12).

The advantage of this procedure is that all inflammatory tissue is removed, the bile duct and pancreatic duct are relieved and no longer congested, but the neck of the pancreas does not need to be transected (Fig. 12). This also means that only one new connection from a loop of small intestine to the head of the pancreas needs to be made, which reduces the risks of leakage (Fig. 13).

What happens after the operation?

As after any major abdominal surgery, the patients are treated in the intensive care unit for two to three days. Monitoring of respiration, circulation and urine output as well as the administration of painkillers and infusions takes place around the clock. The patients receive an antibiotic and a special agent to inhibit secretion (somatostatin) for seven days. Read more >

At the same time, some blood values are closely monitored: Lipases, amylases and blood glucose, which may need to be controlled with additionally administered insulin. After leakage control, an amylase determination from the abdominal secretion of the drains, these are removed after four days, and the food build-up begins carefully with the gastric tube in place. Some patients may experience temporary gastric emptying disorders. Over the course of the next few days, it will then be possible to assess the extent to which pancreatic function is impaired and whether replacement of digestive enzymes and administration of insulin will be necessary in the long term.

In the fig. 14, a CT scan six months after surgery shows a decrease in calcifications in the body and tail and a decompressed and restored pancreatic duct to normal caliber.

What must be paid attention to in the future everyday life?

Studies in a large number of patients with chronic pancreatitis have shown that surgery can halt an impending loss of function of the remaining pancreatic tissue, thereby significantly improving the patient’s quality of life. Even if the patient, even after a total removal of the pancreas, has to permanently replace his digestive enzymes as well as insulin, but avoids the risk factor alcohol, he can lead an almost normal life in the future.

Historical

Alexandria around 300 B.C.: In their heyday, the Ptolemaic kings built a large university and library to allow scientists, artists and writers to research and teach. The physician and anatomist Herophilus of Chalcedon also worked here, as it was permitted at this university to conduct anatomical studies on cadavers – an activity that was strictly forbidden in other countries. The first more detailed descriptions of the pancreas and liver came from him. Read more >

Johann Georg Wirsung, professor of anatomy in Padua, discovered the large excretory duct of the pancreas in 1642, which is still named after him today: Ductus Wirsungianus. “But (…)”, he wrote to his teacher Jean Riolan, not knowing what he had actually found, “(…) should I call it artery or vein? I never found blood in it, but I did find a cloudy juice that acted on the silver probe like a corrosive liquid (…)”. The story came to a bloody end: a year after his discovery, Wirsungianus was murdered on his doorstep by a student. Was there a dispute about who had been the actual discoverer of the passage?

In 1869, Paul Langerhans, a medical student of only 22 years of age, came across the islet cells of the pancreas as part of his doctoral thesis, but did not know what function they performed. About twenty years later, Oskar Minkowski and Joseph Freiherr von Mering removed the pancreas from a dog to observe the effects on sugar metabolism. The dog developed all the symptoms of diabetes, and the two researchers were able to detect glucose and acetone in the urine. This demonstrated the link between pancreatic dysfunction and subsequent development of diabetes. After Frederick Grant Banting and Charles Best discovered the substance produced by the islet cells, namely insulin, around 1920, it took only three years for the first insulin preparation to come onto the market – saving thousands of diabetics patients, for whom there was no hope before

The great surgeons of the time still considered the pancreas to be an “surgeon-hostile organ” with regard to its anatomical location and its inherently fragile tissue. The surgeries were extremely surgically challenging and high risk for the patient. But the surgeon Carl Gussenbauer, successor of Theodor Billroth in Vienna, was an innovative mind. He had already developed the first artificial larynx as an assistant and was not deterred by such a delicate situation as that of the pancreatic pseudocyst, a complication of chronic pancreatitis. He found a procedure that allowed the fluid to be drained from these cysts.

In 1909, Walter Kausch broke new ground in Berlin by performing the first radical pancreatectomy, which always included removal of parts of the stomach and duodenum. In the 1930s, Allen O. Whipple revisited this technique for removal of a pancreatic tumor, but performed it in two separate procedures because of the high surgical risk. Since then, the “Whipple thimble” has been further perfected by many great surgeons, and the procedure has at the same time become a standard unilateral procedure that is also very safe for the patient.