Extra Information

Warning

The diseases described on the following pages contain images and film material taken during operations. Decide for yourself if you want to see these images. Please also note our imprint and the legal information. The Baermed practice assumes no liability. Do you really want to see the page!

Liver

Topics

1. Liver and Liver Diseases

One of the largest organs in the body

Liver is one of the largest organs in the body with numerous important functions for metabolism. It converts nutrients from food into substances that the body can use, stores them, and releases them to the cells when needed.

Primary and secondary malignant tumors (metastases)

In medicine, there is a basic distinction between primary and secondary malignant tumors (metastases). Primary malignant liver tumors arise from the liver cell itself or from cells of the bile ducts located in the liver tissue. Secondary tumors, commonly referred as metastases, are scattered cells from a malignant tumor that originated from another organ, such as the colon, rectum, or kidney.

A new treatment for severe chronic liver cirrhosis!

Baermed is currently conducting a study approved by the Zurich Cantonal Ethics Committee (KEK) and the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (BAG), which has been notified to www.clinicaltrials.gov. The following summary provides more information about this study.

Where is the liver located?

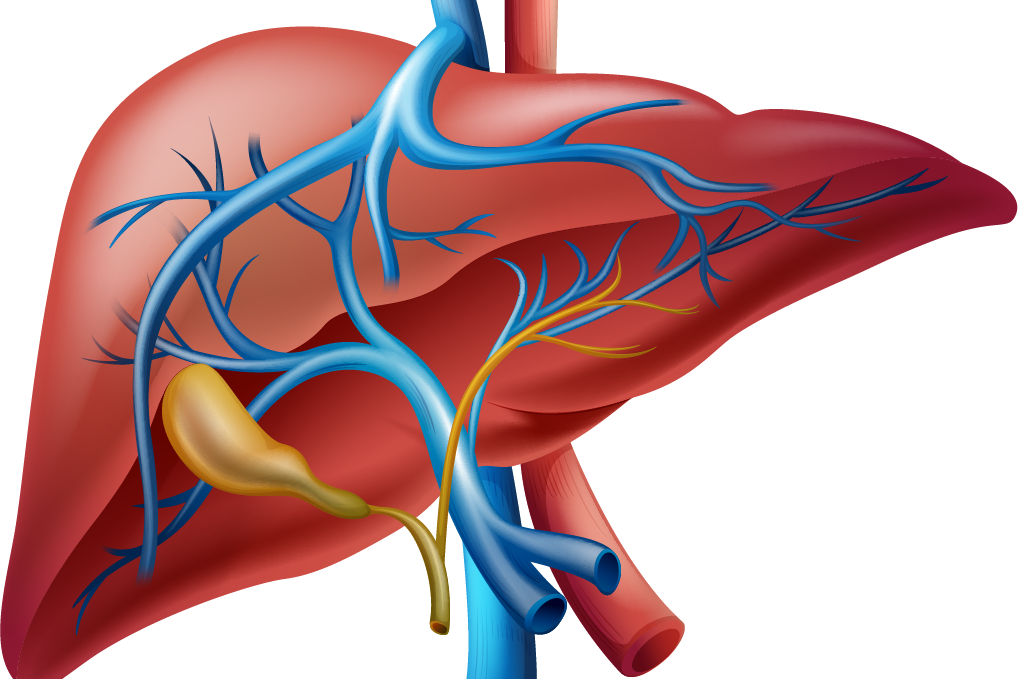

With an average weight of one and a half kilograms and a volume of three liters, liver is one of the largest and most important organs in humans (Fig. 1). It is located 3/4 in the upper right abdomen and its shape resembles an oblique, three-sided pyramid. At the top, it is attached to the diaphragm and therefore sinks down during exhalation; which the physician can take advantage of when palpating and delineating the lower border of the liver. At the lower side of the liver, the gallbladder and inferior vena cava press so deeply into the tissue that there is an asymmetric, external “liver division” into a small left-sided portion and a large right-sided portion. Read more >

However, this external appearance contrasts strongly with the very symmetrical internal structure of the liver, which has been divided into eight segments (sections) since Claude Couinaud. This internal symmetry results from the regular allocation of one vein, one artery, and one bile duct to each of the eight segments. The large afferent vein, the portal vein and artery, and the hepatic artery enter the liver at the porta hepatis. The vein brings oxygen-poor but protein-rich blood from the intestinal and stomach regions to flow through the “liver filter” and be detoxified durign the process. Immediately after the blood enters, the portal vein divides into left and right branches. Both branches further divide and form the portal vascular tree of the liver. The artery which supplies the liver tissue with oxygenated blood, also divides into several branches and forms the arterial vascular tree of the liver.

After passing through the liver, the blood continues to flow via the third vascular tree (i.e. via the large hepatic veins) into the inferior vena cava and towards the heart. At the same time, the bile produced in the liver cells is transported out of the liver in the opposite direction in the area of the hepatic porta, and partially stored in the gallbladder and excreted via the duodenum for digestion of food. Even until today, this complex internal structure of the liver still pushes highly qualified liver surgeons to their operational limits when they attempt to save a small piece of healthy tissue, in the case of extensive tumor invading the liver, in order to provide the patient with optimal surgical therapy.

1 Liver

2 Stomach

3 Spleen

4 Pancreas

5 Large intestine

6 Small intestine

7 Gall bladder

Often no characteristic symptoms

Often, patients with hepatocellular carcinoma do no show particular symptoms. Frequently, changes in the liver, especially in the early stages, are a diagnostic incidental finding. Patients with hepatitis must therefore be examined periodically with ultrasound or CT. Regular checkup on liver parameters is also important.

How does the liver work?

As a blood filter between the intestine and the rest of organs, the liver carries a wide variety of complex tasks in human metabolism. It produces important substances itself (blood clotting substances and cholesterol), maintains the balance of many substances (sugars, fats, hormones, vitamins) and helps to eliminate drugs, waste products and toxins from the body. In addition, as the largest gland, it is responsible for the production and release of bile; thus plays a crucial role in the digestion of fat in the intestine. Read more >

Therefore, a functional impairment of the liver tissue, caused by tumors or inflammations, has more or less serious consequences: Sugar metabolism can derail (hypoglycemia), proteins are insufficiently produced (blood clotting disorders, abdominal dropsy), and bile salts/bile pigments are insufficiently removed (itching and yellowing of the skin). One of the most important properties of the liver, however, is its enormous capacity to regenerate: if one has to remove a large amount (up to 75% maximum) of liver tissue as a part of liver resection, one will notice a compensatory enlargement of the remaining liver after a while. Under the influence of messenger substances, there is a proliferation of liver cells on the one hand, but also a significant enlargement of the existing liver cells on the other hand.

Ode to the liver

by Pablo Neruda, Nobel Prize winner for literature in 1971

…

There, inside,

you filter and apportion,

you separate and divide,

you multiply and lubricate,

you raise and gather the threads and the grams of life,

…

From you I hope for justice

I love life: Do not betray me!

Work on! Do not arrest my song.

2. Malignant Liver Tumor

Symptoms, treatment and surgery for liver disease

Most common liver diseases

Generally, the most common liver disease is inflammation called “hepatitis”. Various viruses are known to specifically attack liver cells, multiply within them, and ultimately destroy liver cells. For example, hepatitis A, B, C or E. Treatment is carried out by specialized internal medicine physicians, gastroenterologists and hepatologists. Congenital malformations can also frequently occur in the liver, such as liver cysts or hemangiomas (for more information, see our patient information “Benign Liver Tumors”). They are mostly trivial and do not need to be treated. Read more >

The true neoplasms (Latin: tumors) of the liver tissue must be clarified in detail, because both benign and malignant tumors can be found among them. In this patient information, we particularly describe the malignant neoplasms. The benign tumors are described in our patient information “Benign Liver Tumors”.

In medicine, there is a basic distinction between primary and secondary malignant tumors (metastases). Primary malignant liver tumors arise from the liver cell itself or from cells of the bile ducts located in the liver tissue. Secondary tumors, commonly referred as metastases, are scattered cells from a malignant tumor that originated from another organ, such as the colon, rectum, or kidney. Much is known about the development of the most common primary tumor of the liver, hepatocellular carcinoma (Latin: hepatocellular carcinoma, often abbreviated to “HCC”), that several factors are causally involved: viruses (hepatitis), hormones, chemicals (solvents, pesticides), alcohol and other noxae.

HCC can grow in liver tissue both as a single nodule, as well as scattered or diffused. Much rarer case is cholangiocarcinoma (often abbreviated to “CCC”), which arises from the “lining tissue” of the bile ducts, whose cause is still unknown. Gallstones are also often found in affected patients and in this context, a chronic inflammatory stimulus caused by these stones could cause the development of a tumor. The appearance of this tumor in liver is characterized by individual tumor nodules with a high proportion of connective tissue, recognizable by its central scarring. Occasionally, a mixed form of these two tumors (HCC + CCC) is also found in the liver, the difficult diagnosis of which must be made by a pathologist after a careful tissue preparation and evaluation.

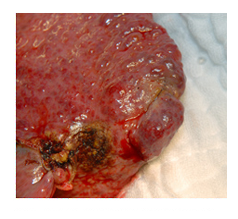

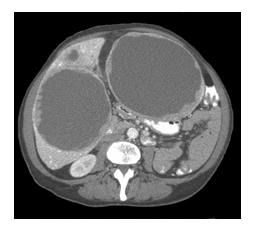

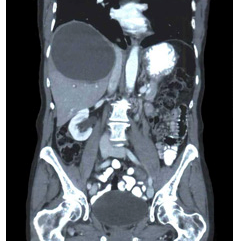

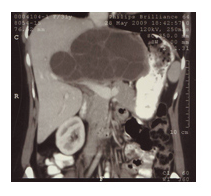

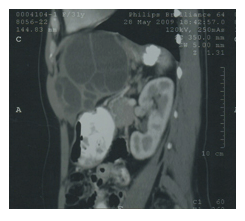

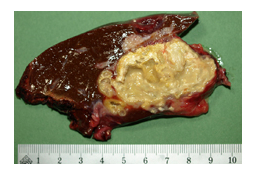

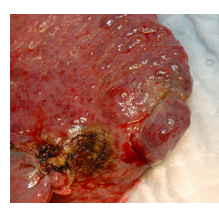

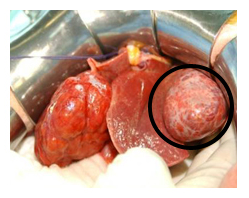

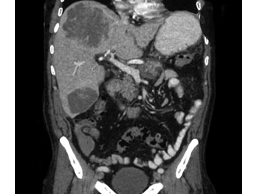

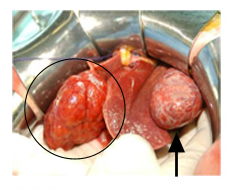

Compared with these rare primary carcinomas of the liver, the secondary malignant tumors of the liver, liver metastases (Figs. 2a, 2b, 3a, and 3b), are found much more frequently.

How do I recognize a malignant liver tumor?

Often, patients with hepatocellular carcinoma do no show particular symptoms. Frequently, changes in the liver, especially in the early stages, are a diagnostic incidental finding. Patients with hepatitis must therefore be examined periodically with ultrasound or CT. Regular checkup on liver parameters is also important. Unfortunately, the soft liver tissue yields so well to even large space-occupying lesions that capsular tension pain of the liver occurs relatively late in the course.

In bile duct carcinoma, obstruction of the bile ducts and, in HCC, loss of too much functioning liver cell mass can lead to yellowing of the skin and thus provide an initial indication of a tumor.

Diagnosis and Necessary Clarifications of Liver Disease

Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma often have no characteristic symptoms. Frequently, changes in the liver, especially in the early stages, are a diagnostic incidental finding. Patients with hepatitis must therefore be examined periodically with ultrasound or CT. Regular checks of liver values are also important. Unfortunately, the soft liver tissue also gives way to large space-occupying lesions so well that capsule tension pain in the liver only occurs relatively late in the course.

The physician in charge must first obtain a detailed medical history and perform a thorough physical examination. Questions about pre-existing conditions, dietary habits, previous surgeries and blood transfusions (hepatitis) that have taken place, weight loss, and pain are important. Physical examination includes an approximate assessment of liver size and consistency (Fig. 4). Read more >

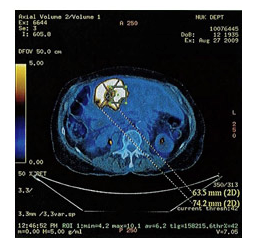

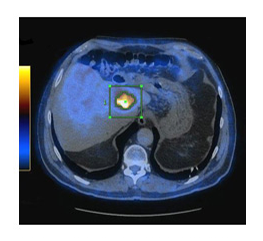

Further, the color of the skin is checked, and itching is asked for. In addition, according to the multiple functions of the liver, the most important blood values will be determined: Blood count, coagulation status, liver values, blood sugar level, total protein and tumor markers. The ultrasound is still an excellent way of providing the physician with a quick orientation regarding the disease, since it is necessary to find out whether the tumor is benign or malignant and whether it originates from the liver itself or is a metastasis, for example. After that, a decision can be made about further diagnostic procedures such as CT, MRI (combined with contrast agent administration), angiography or PET scan (Fig. 5).

A tissue sample will only be taken in exceptional cases, as there is always a risk of tumor cells being carried away and the risk of bleeding. If the diagnosis of a malignant tumor has been made on the basis of all the available findings, different treatment paths must be followed depending on the findings.

If the treatment of choice is surgical, there are still two basic questions to be addressed from a surgical perspective:

- Do the patient’s age and physical condition permit such a major procedure? Additional examinations of the heart (ultrasound) and lungs (functional test) are often necessary to clarify this question.

- The second question the surgeon must ask is the surgical concept: In which part of the liver is the tumor located? Is it one node or are there several? From which parts of the vascular tree is this section of the liver supplied? Which bile ducts run here? How much healthy liver tissue remains after tumor removal? Is this sufficient to guarantee the survival of the patient? Is it a primarily malignant tumor or is it a metastasis?

Liver function diagnostics must also be performed before surgery (e.g., by determining the galactose elimination capacity or by the indocyanine green test). These examinations provide information on whether the liver still has sufficient functional tissue, apart from the tumor. Liver surgery also requires “high-tech” management on the part of anesthesia. Read more >

This includes the preoperative examination, explanations regarding the creation of arterial and venous accesses, the provision of blood supplies and information regarding postoperative care in the intensive care unit. If the patient’s physical condition or the location of the tumor argues against surgery, an interdisciplinary team of surgeons and oncologists will meet to decide on the next course of action, for example, chemotherapy or locally applied treatments with heat, cold or radio wave irradiation.

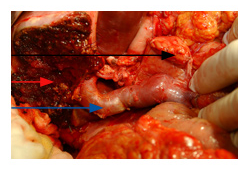

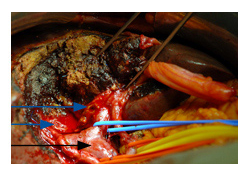

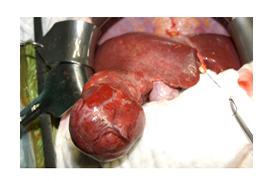

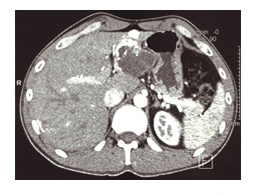

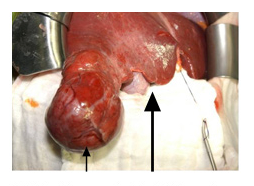

Very rare tumors that occur as metastases in the liver can be so-called neuroendocrine tumors, which usually originate from the pancreas and settle in the liver (Fig. 6). They grow like malignant tumors, but often very slowly and somewhat confined to the affected organ. Therefore, combination operations on the liver and pancreas are indicated here. However, after surgery, oncological therapy must also be used.

Red arrow: liver slice area

Black arrow: Pancreas

Blue arrow: portal vein

How can a malignant liver tumor be treated?

Partial liver resections are necessary for various diseases, such as benign and malignant liver tumors, metastases, parasite infestation of the tissue (fox tapeworm) or gallbladder and bile duct tumors. Depending on the disease, size, extent and especially location of the tumor, different partial removals are performed. For example, we speak of right and left partial liver resection or extended liver resection. Read more >

An example:

Right hepatectomy involves removal of the segments V, VI, VII and VIII on the right side. If it has to be extended, segment IV, which is located further to the left of the gallbladder, is still added as a standard. Removing as much as necessary and as little tissue as possible is the surgeon’s maxim and desire. Unfortunately, due to the highly complicated anatomy of the liver, this is often no small matter, even for the specialist. This also includes a certain safety margin in the case of malignant tumors. As an example of the many different procedures of partial liver resection, the basic procedure of which is similar, the right hemihepatectomy already mentioned above will be described below.

During surgery, the patient lies in the supine position with the right arm extended and the left arm flexed. The skin incision is made along the left and right costal arches and is extended upward a little as needed, centered over the sternum, to create the image of a “Mercedes star” (Fig. 7).

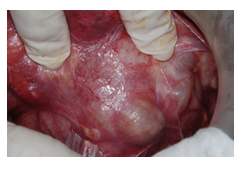

After cutting through the abdominal wall, the surgeon will first use both hands to circumnavigate and palpate the liver (tumor and tissue assessment) and examine the adjacent organs. This is followed by partial mobilization of the liver by loosening or partially severing certain suspension ligaments of the organ to the abdominal wall and diaphragm. Subsequently, an intraoperative examination with ultrasound is performed to determine the exact location of the tumor, to clarify the resection options and to rule out other tumors. Depending on whether or not the preliminary findings match the local findings found, the surgeon will decide to reconsider his approach. Basically, there are now two different technical routes that can be taken to remove liver tissue:

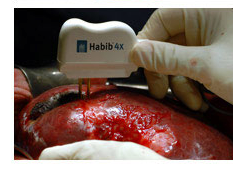

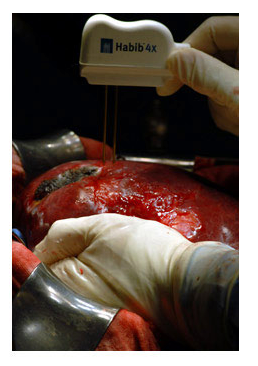

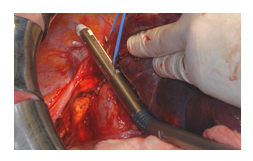

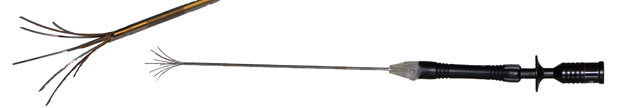

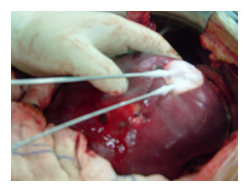

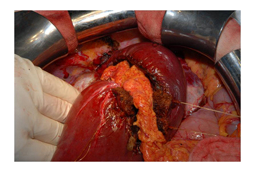

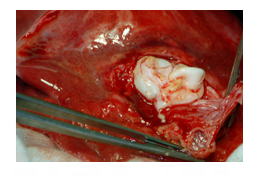

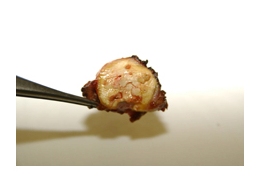

All important supplying and draining vessels including the bile ducts are blocked, after which the actual transection of the liver tissue can be carried out using various methods. Tissue dissection with the finger “finger fracture technique” or with devices that facilitate tissue hemostasis (such as an ultrasound dissector or the Habib Sealer), (Figs. 8a and 8b).

First, the liver tissue is transected while controlling blood flow, then the vessels are tied off.

A tissue sample will only be taken in exceptional cases, as there is always a fear of spreading tumor cells and the risk of bleeding. If the diagnosis of a malignant tumor has been made on the basis of all the available findings, different treatment options must be pursued depending on the findings.

The procedure varies from surgeon to surgeon and from situation to situation. If the surgeon follows the first option, he usually aims to expose the hepatic portal, because this is where the large arterial and venous vessels and bile ducts that run into the liver run in a thick strand of tissue (Latin: Ligamentum hepato-duodenale). This is done by dissecting until the gallbladder and its supplying vessels are exposed. Read more >

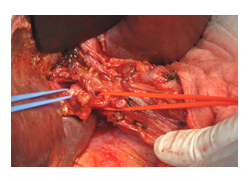

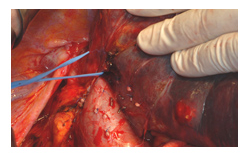

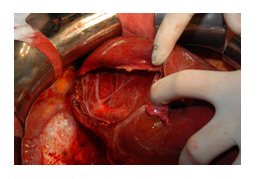

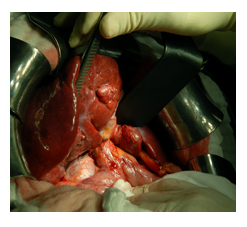

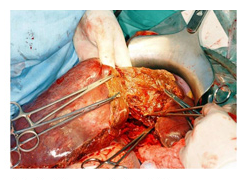

The gallbladder is removed for the following two reasons: the surgeon has a better view of the hepatic portal, which is important for him (Fig. 9), and after the surgery he avoids the occurrence of complications that may arise in the gallbladder area (inflammation). Now the lymph nodes in the area of the hepatic portal are closely inspected, removed and examined by the pathologist. The thick tissue strand of the hepatic portal is looped with a rubber tube so that the blood flow can be controlled at this point during the surgery (Pringle maneuver). The cord is now carefully dissected so that the relevant right-sided artery, portal vein and bile duct are finally exposed.

The vessels and bile duct to the right are clamped in the hepatic portal, pierced and interrupted, or closed with special stapling devices and cut at the same time. The large draining vein in the upper portion of the liver is carefully dissected free and also cut (Figs. 10 and 11).

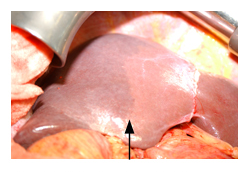

This interrupts the blood inflow and outflow to the areas to be resected. This liver tissue, which is no longer perfused, discolors and usually shows a nice border to the normally perfused tissue (Fig. 12).

The right portion of the liver is further mobilized to allow visualization of draining blood vessels posterior to the liver that run from the liver to the large body vena cava. Subsequently, the liver tissue is cut. A wide variety of safe methods are used today for gentle transection of liver tissue, such as clip application, diathermy or clamp technique with stitching. Large diffuse hemorrhages from liver tissue can be stopped by argon gas coagulation, smaller ones by electrical diathermy. After cutting through the resection layer, the removed portion of the liver, which contains the disease-causing tumor, is sent to the pathologist for histological examination. It is important in this operation that there is sufficient distance from the resection surface to the tumor margin. Read more >

The surgeon’s most important task now is meticulous hemostasis. The severed tissue areas are “drained” with argon gas coagulation, and any vascular ligations that have occurred are controlled. Particular attention is paid to the severed bile ducts, because here too there must be no leakage under any circumstances postoperatively. Often, a drain will be placed in the surgical area. This is followed by the layer-by-layer closure of the abdominal wall.

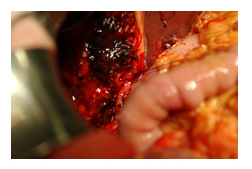

Depending on the underlying disease, for example in the case of metastases, a combination treatment for surgery with local chemotherapy or even heat therapy (Fig. 13 Cold (Figs. 15 and 16), and laser therapy may be useful to completely destroy the tumors.

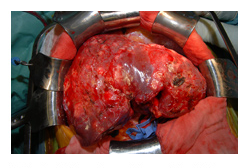

Following the basic principle described above, many liver surgeries are performed, often forcing the surgeon to choose atypical variants due to the local findings, always keeping in mind that the remaining liver tissue receives good venous and arterial blood flow. Liver tissue removal can be dangerous if the entire organ is diseased and the liver has already developed into fibrosis or even cirrhosis (Fig. 17). Cirrhosis means a transformation of the smooth liver tissue into smaller or larger nodules, resulting in a loss of function of the entire liver.

If additional tissue is lost due to surgery, the function may be further reduced. After chemotherapy, in the presence of a fatty liver, or later in the event fibrosis or cirrhosis, the cut surface of the liver may bleed profusely. Here, coagulation devices, such as the Habib Sealer and the argon beam, but also other methods to cut off the blood supply, such as fibrin glue, play a major role in hemostasis. Read more >

If primary malignant tumors or liver metastases are too large for resection, then various tumor reduction procedures are used today prior to surgery. All procedures attempt to preserve as much healthy liver tissue as possible and to shrink the tumor. For liver metastases from colon cancer, for example, chemotherapy is first carried out in order to shrink the tumors or to destroy smaller metastases that are invisible in the imaging diagnostic methods. If the tissue of the liver remaining after surgery is too small, then by occluding a portal vein branch to the left or right liver portion, the liver portion excluded from the portal vein blood can be reduced, and the opposite portion enlarged. This closure can be achieved by specialists in interventional radiology through a small incision in the groin and by advancing special catheters through the veins into the portal vein.

With the occlusion of a portal venous branch, a so-called hypertrophy (enlargement)-atrophy (reduction) complex is successfully artificially created. This possibility is based on the well-known fact that when liver tissue is lost, the tissue left behind can compensatorily increase in size again to a very large extent. However, in the presence of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis, the remaining liver can no longer enlarge sufficiently.

Intraoperative views of various findings follow (Figs. 18, 19 and 20).

Black arrow: portal vein

Blue arrows: view of the left and right intrahepatic bile duct.

What happens after the treatment?

After any major liver surgery, the patient is initially transferred to the intensive care unit for one to two days. Here, adequate pain therapy and balanced infusion therapy are carried out above all. Furthermore, liver values are checked regularly, and close monitoring ensures that any complications that arise, such as secondary bleeding, are detected immediately. In the normal ward, the patient is then given a diet and mobilized. The skin sutures are removed on the tenth day after surgery. Depending on the disease, surgeons and oncologists may still consult about additional treatment in the form of intravenous chemotherapy and discuss this with the patient.

What must be paid attention to in the future everyday life?

All patients with malignant liver tumors are managed in a special and regular follow-up program by their primary care physician and by gastroenterologists, oncologists, and surgeons who are in contact with each other. This program includes laboratory checks to follow the progression of tumor markers and liver enzymes, as well as ultrasound and/or CT or MRI examinations of the abdomen to assess regeneration of the remaining liver, but also to see new tumor metastases at an early stage.

Historical

The liver already played a major role in Greek mythology, more precisely in the Prometheus saga. Prometheus (ancient Greek = the provident) created mankind from clay. When the Gods demanded sacrifice and worship from humans, Prometheus tried to trick Zeus, but to no avail. As punishment, Zeus withdrew the fire from the people. But Prometheus succeeded in bringing the fire back to earth. Eventually Zeus had him captured and chained to a rock, whereupon an eagle would come and eat his liver every day. However, this renewed itself at night, since Prometheus was one of the immortals. Prometheus pleaded for mercy and redemption until Heracles eventually released him from his suffering. Read more >

With this legend, among other things, one of the most important properties of the liver is indicated: its ability to regenerate. For centuries, it was primarily the war surgeons who attempted to treat open liver injuries. It was not until the establishment of general anesthesia and antisepsis at the end of the 19th century that Karl Langenbuch was able to perform the first liver surgery in 1888. At the same time, the scientific basis for liver regeneration and hemostasis in the liver were explored during this period. Between 1899 and 1914 there was a scientist, the Viennese surgeon Emerich Ullmann, who advanced transplantation research relatively unnoticed and who in retrospect has to be called the father of organ transplantation. However, the foundation stone for modern liver surgery was laid by the great Parisian school around Jacques Hepp in the 1950s.

In 1954, one of his colleagues, Claude Couinaud, published the standard work on liver anatomy. He described the complex, internal division of the liver into eight segments, which were determined by the location of the hepatic veins and by the location of the bile ducts. In the meantime, transplantation immunology had also made great progress, so that in 1967, despite inadequate immunosuppression, the first successful liver transplantation of a patient by Tom Starzl could be carried out. The scientific struggle for potent immunosuppressants continued until 1972, when a substance (cyclosporine) was obtained by chance from a soil fungus, which was able to reliably suppress the rejection reaction of an organ in the body and then caused the survival rate of transplanted patients to skyrocket.

3. BENIGN LIVER TUMOR

The most common benign tumors of the liver

Control and aftercare program

All patients with malignant liver tumors are managed in a special and regular follow-up program by their primary care physician and by gastroenterologists, oncologists, and surgeons who are in contact with each other. This program includes laboratory checks to follow the progression of tumor markers and liver enzymes, as well as ultrasound and/or CT or MRI examinations of the abdomen to assess regeneration of the remaining liver, but also to see new tumor metastases at an early stage.

The blood sponge (hemanigoma)

The most common benign liver tumor is the hematoma, Latin hemangioma (Figs. 3, 4 and 5), which results from a proliferation of the supporting cells of the blood vessels and can range in size from several millimeters to several centimeters.

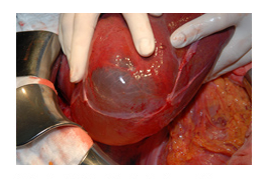

Hemangiomas appear in the liver as a well-defined structure within the liver tissue, often also on the edge of the liver tissue, from which they can become very large and protrude into the abdominal cavity as roundish structures. They are often surrounded by a thin capsule on the outside and separated from the normal liver tissue by a separating layer, from which they can be operated on relatively easy. If they are larger than 9 cm they are called giant hemangiomas. Hemangiomas are likely congenital and do not continue to grow. They do not degenerate even after long observation and only need to be treated if they cause discomfort (feeling of pressure) because of their size.

Liver cysts

Cysts may also be found in the liver, as in other organs such as the kidney (Figs. 6, 7, and 8).

A cyst, has a thin capsule lined with an endothelium (inner layer) that secretes a fluid. The cyst fluid inflates the cyst like a balloon, which usually gives cysts a rounded spherical shape that is also easily seen on computed tomography (Figs. 9a and 9b). Cysts are very commonly found during routine ultrasound examinations and are insignificant up to a size of six to nine centimeters. Most likely, cysts are congenital malformations that are completely irrelevant. Read more >

Only when they exceed nine centimeters in size, effectively causing pain or increasing in size, they have to be treated surgically. Besides these so-called simple cysts, there are also complicated cysts. They are so called because their contents on ultrasound or CT do not show clear fluid as their contents, but subdivisions by septa, hemorrhage, or because their interior shows an indefinable content (Figs. 9a and 9b). Here, the differential diagnosis to other possibly more dangerous liver diseases is important. However, simple cysts are relatively easy to detect with imaging methods.

A specific hereditary disease is cystic liver. In this disease, the liver tissue is diffusely interspersed with many larger and smaller cysts. Cystic livers can grow grotesquely and usually cause mechanical problems with pain and digestive problems for those affected. This disease affects not only the liver but also the kidneys, which are also so heavily riddled with cysts to such an extent that over time there is no longer sufficient kidney function. In the case of pain, mechanical disorders and digestive problems, these cysts can be reduced in size – often laparoscopically – by removing the cyst roofs that are exposed on the surface.

Echinococcus cysts

For the sake of completeness, it is necessary to mention the cystic tumors of the liver caused by the dog and fox tapeworm (Latin Echinococcus). This is also referred to as cystic (E. cysticus) and alveolar (E. alveolaris or multilocularis) echinococcosis. They are often readily visible on CT (Figs. 10, 11 and 12).

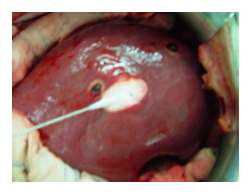

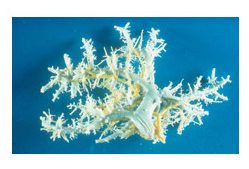

These diseases are zoonoses, i.e. actually diseases of vertebrates (e.g. sheep), which can be transmitted to humans because humans appear as an accidental intermediate host in the development cycle of the tapeworms when infected. In the case of infection by the dog tapeworm, a water sac surrounded by a capsule forms in the liver or lungs of humans from the ingested larva. The larvae of the fox tapeworm, on the other hand, penetrate the liver with many hazelnut-sized vesicles and destroy or displace the healthy tissue. The fluid in these blisters in turn contains larvae, which is a major challenge for surgical and chemotherapeutic therapy because these blisters must not burst to prevent spread of infection (Figs. 13 and 14).

The cysts formed by E. cysticus can usually be surgically removed relatively easily by killing their contents with high-percentage saline solution. Subsequently, the dead echinococci (lat. scolices) are aspirated. The Ulmer funnel (Fig. 15), through which suction is applied without scattering the contents of the cyst in the abdominal cavity, is very helpful.

These echinococci must also be treated with surgery (Figs. 16, 17, 18, 19, and 20), which can be very difficult because the parasite can grow into the bile ducts and vessels and is often very difficult to remove. Both parasite species can be detected with special blood tests in addition to imaging methods. E. alveolaris must not only be operated on but also treated before and after surgery with a special drug (mebendazole).

Benign neoplasms of the liver

The actual benign liver tumors that form from the liver cells themselves are hepatocellular adenoma and focal nodular hyperplasia. An alteration of the liver associated with nodular growth is also liver cirrhosis (Fig. 21). It is often not possible to distinguish cirrhotic nodules from early stages of neoplasia (FNH or hepatocellular carcinoma) on ultrasound, computed tomography, or MRI.

Hepatocellular adenoma

Liver cell adenoma (Fig. 22) is a proliferation of the liver cell itself. It occurs predominantly in women between the ages of 20 and 40. Single adenoma nodules are usually found in the liver, but they can be up to 30 cm in diameter and usually lack a capsule.

In the adenoma node, an accumulation of fats and sugars is found. Associated with this tumor are occasional local hemorrhages and dead liver cells in the nodules, which may cause the first symptoms of upper abdominal pain in 10% of patients. This risk of bleeding, as well as a risk of degeneration (preliminary stage of hepatocellular carcinoma) attributed to the adenoma, are the bases for why a hepatocellular adenoma is now considered a precancerous condition (preliminary stage of a tumor that may lead to malignancy) and therefore usually has to be surgically removed.

Focal nodular hyperplasia

Liver cell adenoma (Fig. 22) is a proliferation of the liver cell itself. It occurs predominantly in women between the ages of 20 and 40. Single adenoma nodules are usually found in the liver, but they can be up to 30 cm in diameter and usually lack a capsule.

In the adenoma node, an accumulation of fats and sugars is found. Associated with this tumor are occasional local hemorrhages and dead liver cells in the nodules, which may cause the first symptoms of upper abdominal pain in 10% of patients. This risk of bleeding, as well as a risk of degeneration (preliminary stage of hepatocellular carcinoma) attributed to the adenoma, are the bases for why a hepatocellular adenoma is now considered a precancerous condition (preliminary stage of a tumor that may lead to malignancy) and therefore usually has to be surgically removed.

How do I recognize benign liver tumors?

As a rule, the discovery of a benign liver tumor is an incidental finding during an ultrasound examination or other diagnostic measures and examinations, because the patients are usually symptom-free. Most commonly, patients with hepatocellular adenoma complain of uncharacteristic pain in the right upper abdomen, as well as bloating, mild nausea, or fever. In comparison with other benign tumors of the liver, slightly altered liver values are sometimes seen here, which may indicate a bile stasis caused by the tumor. Unfortunately, even the already large-volume blisters of the dog and fox tapeworm often cause hardly any symptoms in affected people, so that often only an obstruction of the bile ducts with a subsequent yellowing of the skin gives the only indication of this liver disease.

Necessary clarifications and diagnostic possibilities

Although in most cases the benign liver tumors are detected by ultrasound scan, a detailed questioning and physical examination by the physician is essential, because the sequence of the entire diagnostics must clearly serve the characterization and confirm the benign nature of the tumor. For example, the distinction between hepatocellular adenoma and hepatocellular carcinoma can be extremely difficult despite state-of-the-art diagnostic methods, and in up to 40% of incidentally found changes, clear assignments cannot be made at all. It would be important to know if the patient has lost weight and how long the pain in the upper abdomen has been present. Read more >

Furthermore, it must be clarified whether there was a tumor condition in the past and whether hormones were taken over several years. Does the patient work as a farmer or in forestry, or have contact with animals for other reasons? For further clarification, laboratory values such as blood count, liver values and tumor markers must be determined in order to confirm the benign nature of the tumor. The clarification of the dog and fox tapeworm also requires a special blood test that looks for antibodies against the larvae in the blood.

As the simplest imaging method in diagnostics, an ultrasound is first carried out for all liver diseases and then decisions are made about other imaging methods such as CT (Fig. 24), MRI or angiography in order to obtain an accurate diagnosis. Very specific for tumors is the PET scan examination (Fig. 25). If the diagnosis indicates that a piece of liver needs to be removed, further special tests are performed to check the functionality of the healthy liver tissue.

How can a benign liver tumor be treated?

Treatment procedures for benign liver tumors include medications and surgical measures. The latter are detailed in the chapter “Malignant tumors of the liver”, as the technique of tissue removal is almost identical.

In the case of hemangiomas of the liver, the surgical indication is made with the greatest caution, since the benefit and risk for the patient are disproportionate in this case. So they’re just left in the liver tissue. They are also not punctured because the risk of bleeding is too high. On the other hand, female patients in particular are advised not to use hormones for contraception, as they can stimulate the growth of hemangiomas. Surgical intervention should only be considered in the case of large-volume hemangiomas that are larger than the diameter, or those that cause discomfort to the patient, whereby the risk and benefit must be carefully weighed. Surgically, a procedure called “enucleation” would be performed, which means that the capsule of the hematoma would be peeled out of the liver tissue in toto. Read more >

Hepatocellular adenoma is considered a precursor of hepatocellular carcinoma and is therefore removed surgically in all cases. Depending on the location of the adenoma within the liver, central or peripheral, the surgeon selects the removal technique that completely removes the tumor and spares the healthy liver tissue, while also posing the lowest risk of surgery for the patient. Surgeries in which parts of the liver have to be removed are subject to an increased risk of bleeding due to the highly complicated blood supply to the liver and are often a major challenge for the surgeon.

If FNH (focal nodular hyperplasia) has been clearly diagnosed, it will not have to be operated on, and here too, patients in particular will be advised against taking hormones for contraception. Especially in this disease, scientists assume that its development is triggered by hormones. Often, however, FNH cannot be diagnosed with such certainty, or it causes discomfort due to its location and size, so that surgical removal has to be carried out anyway.

Regarding the therapy of cysts of both dog and fox tapeworm, there are two principles:

- If somehow possible, they are approached surgically, focusing quite strictly on the criteria of tumor surgery, since no larval material may be carried over.

- All patients are treated with the anthelmintic drug mebendazole.

For dog tapeworm cysts, surgery remains the first choice procedure with the goal of radically removing the parasite. The prerequisite for this is above all a “good” location of the cysts so that the surgeon can peel them out without risk (pericystectomy). If the cysts are diffusely distributed in the liver tissue, the surgeon may need to perform a partial liver resection. The more radical the surgery, the less likely the infection will flare up again.

If the general condition of the patient or an unfavorable distribution of the cysts does not allow surgery, there is another procedure that can be used:

- Laparoscopically, i.e. with the help of keyhole surgery, the cyst is emptied in a controlled manner with a special device and the capsule is ground off, at the same time the vermifuge is administered as a tablet. For the cysts of the fox tapeworm, the same principles apply in principle, except that here the larvae usually spread even more aggressively in the liver. Consequently, radical surgical rehabilitation must be sought here as well, if somehow possible. Therefore, an accompanying medication of up to 24 months, possibly even longer, is necessary.

What happens after the treatment?

If an ultrasound has revealed a hemangioma of small size, systematic ultrasound examinations will be performed only for size assessment in the following years. After an adenoma removal, the patient will be cared for in the intensive care unit for one to two days and then mobilized as soon as possible. The liver regenerates its missing tissue part within six to seven weeks. At the same time, the most important liver values are checked to be sure that the liver is once again fulfilling all its “tasks”. Read more >

This means that the patient is cured, but should still receive follow-up care, with ultrasound and possibly CT scans as well as laboratory checks to further monitor the progress. In the case of FNH (Focal Nodular Hyperplasia), patients are also advised to avoid hormone use and undergo regular ultrasound examinations.

The patients with fox or dog tapeworm infection unfortunately have to live with the fact that they have to remain under medical treatment more or less for the rest of their lives. This applies to patients who have undergone surgery as well as those who have received drug therapy. Unfortunately, to date there is no blood test or imaging procedure that proves that the parasites have really been removed 100% from the body despite therapy.

The side effects of the anthelmintic include blood count changes, abnormal liver values, and hair loss. Therefore, close-meshed laboratory examinations to check the active level of mebendazole as well as imaging procedures (CT, MRI) are part of the spectrum of follow-up care.

Historical

The liver already played a major role in Greek mythology, more precisely in the Prometheus saga. Prometheus (ancient Greek = the provident) created mankind from clay. When the Gods demanded sacrifice and worship from humans, Prometheus tried to trick Zeus, but to no avail. As punishment, Zeus withdrew the fire from the people. But Prometheus succeeded in bringing the fire back to earth. Eventually Zeus had him captured and chained to a rock, whereupon an eagle would come and eat his liver every day. However, this renewed itself at night, since Prometheus was one of the immortals. Prometheus pleaded for mercy and redemption until Heracles eventually released him from his suffering. Read more >

With this legend, among other things, one of the most important properties of the liver is indicated: its ability to regenerate. For centuries, it was primarily the war surgeons who attempted to treat open liver injuries. It was not until the establishment of general anesthesia and antisepsis at the end of the 19th century that Karl Langenbuch was able to perform the first liver surgery in 1888. At the same time, the scientific basis for liver regeneration and hemostasis in the liver were explored during this period.

Between 1899 and 1914 there was a scientist, the Viennese surgeon Emerich Ullmann, who advanced transplantation research relatively unnoticed and who in retrospect has to be called the father of organ transplantation. However, the foundation stone for modern liver surgery was laid by the great Parisian school around Jacques Hepp in the 1950s. In 1954, one of his colleagues, Claude Couinaud, published the standard work on liver anatomy. He described the complex, internal division of the liver into eight segments, which were determined by the location of the hepatic veins and by the location of the bile ducts.

In the meantime, transplantation immunology had also made great progress, so that in 1967, despite inadequate immunosuppression, the first successful liver transplantation of a patient by Tom Starzl could be carried out. The scientific struggle for potent immunosuppressants continued until 1972, when a substance (cyclosporine) was obtained by chance from a soil fungus, which was able to reliably suppress the rejection reaction of an organ in the body and then caused the survival rate of transplanted patients to skyrocket.

4. HEMANGIOMA

Cavernous hemangioma of the liver

Where do hemangiomas occur?

Hemangioma can manifest itself in various organs, for the most part on the skin. There it is more commonly known as “blood sponge” or “fire stain” (nevus flammeus). However, hemangiomas also occur in the kidneys, lungs, brain or spleen, and up to about 30% in the liver.

Common benign tumor

Hemangioma is the most common benign tumor of the liver. The size of the hemangioma varies from a few millimeters to more than 20 cm. Hemangiomas usually present as well demarcated structures in the liver. They are often enclosed by a thin capsule (Fig. 2).

Follow-up studies over years have shown that they are unlikely to degenerate. In up to 20% of cases, they occur in multiples. More often women (in 60% of cases) are affected around the age of 40 than men. (Incidence: 0.4 – 2 / 100,000 population).

These well-demarcated tumors become symptomatic only when they exceed a certain size. Hemangiomas larger than 10 cm in diameter are also called giant hemangiomas. They often grow at the edge of the liver and are fixed as spherical structures like appendages to the liver margin (Figs. 3 and 4).

However, they can also be located in the middle of a liver lobe or occur in multiple locations in the liver. They have a very strong arterial blood supply, often with anatomical vascular variations. The vascular anomalies cause huge hemangiomas to have a lot of blood in the “blood sponge” and even circulatory problems because of arterio-venous connections (connection of arteries directly to veins). A rare but dangerous problem is the risk of Kasabach-Merritt syndrome, in which, because of arterial blood congestion or thrombosis that has occurred within the hemangioma, platelets are over-consumed. Anemia could also occur with the symptoms of fatigue, weakness and lack of resilience. Read more >

Usually, hepatic hemangioma does not cause any physical symptoms. Only in the case of giant hemangiomas do patients report general, non-specific symptoms such as a feeling of pressure or swelling in the upper abdomen. Sometimes the hemangiomas themselves are palpable, but most often the enlarged liver is palpable through the abdominal wall. In slender individuals, smaller hemangiomas are sufficient for patients to notice.

Symptoms include non-specific upper abdominal pain and a feeling of fullness or discomfort, especially in the upper abdomen. These symptoms can be explained by imagining that the tumor is pressing on the stomach from the liver, for example, and constricting it. In the case of a giant hemangioma, there is a risk of thrombus formation (blood clots) in the tissue of the hemangioma; rupture (rupture) may also rarely occur after an accident involving direct force to the liver. However, spontaneous rupture of hemangiomas is very rare.

How are hemangiomas of the liver detected?

The hemangiomas are often found as an incidental finding during an imaging study. Most often, this happens during a clarification at the doctor with ultrasound. In this examination, most of the hemangiomas can be diagnosed without any doubt. Giant hemangiomas are present in 30% of cases, and their definitive diagnosis requires further imaging methods, such as computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 5) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Puncture in cases of suspected hemangioma is largely avoided nowadays. Firstly, it is not without risk, since an injury to the vessels can lead to severe bleeding in the abdominal cavity, and secondly, because the informative value of today’s examinations with an MRI very informative. The blood values in the laboratory test are usually unremarkable.

How is a hemangioma of the liver operated on?

Usually, hemangiomas that do not cause symptoms are only monitored continuously. Rarely, there is growth of the hemangioma as well as discomfort on the part of the patient. In the case of progressive rapid growth, it must be clarified precisely that it is not a very malignant hemangioendothelioma. The majority of hemangiomas especially under a size of 5 cm in diameter are harmless and remain harmless. Prophylactic removal of a hemangioma is not recommended. A pregnancy does not have to be terminated. Read more >

The indication for therapy depends on whether there are actual symptoms, or rapid growth, on the part of the hemangioma. It must be carefully clarified whether diffuse upper abdominal pain does not have another cause. Therapy may only be initiated if there are proven problems.

There are several non-surgical options, but they have little prospect of lasting success and their use is controversially discussed:

- Angiography (vascular imaging) and embolization (occlusion) of the arteries supplying the hemangioma. In the case of larger hemangiomas, the hepatic artery that leads to the hemangioma can be ligated or occluded radiologically (through the vessels). Although this therapy should result in decreased blood supply to the hemangioma, it is often unsuccessful because further growth of the hemangioma is possible via collateral arteries. New vessels are formed very quickly.

- Local irradiation of the hemangioma does lead to a temporary reduction in the size of the tumor and can thus reduce the symptoms. However, radiation is not a definitive therapy since a hemangioma can grow again and cause symptoms again.

- The administration of medication (cortisone, interferon α2a) is often discussed, but is not an effective therapy. The long-term side effects and the low efficacy of the drugs actually prohibit such a treatment.

If there is an indication for surgical intervention, two fundamentally different procedures are known:

- The so-called “enucleation”, the peeling out of the hemangioma including the capsule without liver tissue. The normal partial liver resection and thus the removal of the hemangioma and parts of the liver.

This enucleation (Fig. 6) (synonym peeling) is possible in most cases because there is a normally good boundary between the hemangiomatous tissue and the normal liver tissue. Removal in this boundary layer is often performed with an ultrasound dissector and is possible with virtually no blood loss. Vessels and structures that draw from normal liver tissue to the hemangioma must be found, accurately visualized, and securely ligated.

- Often it is also necessary to stop additional, aberrant vessels far outside of a hemanigoma to prevent major bleeding. It is clear that tissue composed mainly of blood-filled cavities has the potential to bleed profusely. Therefore, it may often be necessary to embolize a hemangioma prior to major surgery, i.e., to occlude the vessels supplying blood to the hemangioma by radiological intervention from the external. This can reduce the great risk of bleeding during the operation.

With the technique of enucleation, the risk of massive, uncontrollable bleeding occurring is greatly reduced. In our view, therefore, it is the method of choice for interventions in hemangiomas of the liver (Fig. 7).

Despite the safe technique of enucleation and the low blood loss with this procedure, the surgeon must always be prepared for major bleeding. If intraoperative bleeding is unstoppable, it may be necessary to stop the hepatic bleeding with the insertion of compressive abdominal drapes. The patient must then be ventilated in the ICU for 24 to 48 hours until the bleeding stops during this time. Afterwards, the cloths are removed again.

We perform partial liver resection only when enucleation is no longer possible. For example, in anatomically poorly accessible hemangiomas without a secure separating layer between hemangioma and liver tissue.

What happens after the surgery?

After the surgery, the patient is transferred to the intensive care unit and closely monitored until the risk of secondary bleeding has passed after one to three days. During this time, resuscitation may be given, the pulse, heart rate and blood pressure are checked, as well as urine output and drainage of abdominal drains. Depending on the size of the procedure and intraoperative blood loss, monitoring for one to three days is indicated.

Read more >

In the intensive care unit, as well as in the normal ward, adequate pain medication is considered, which is adjusted every day. A moderate physiotherapy supports the healing process and prevents the development of pneumonia. Liver function is checked regularly by taking blood samples.

After 10 to 14 days it is possible to go to rehabilitation to restore the old constitution. Follow-up ultrasound examinations should be performed several times until the second month after the surgery.

What must be paid attention to in the future everyday life?

After the healing process is completed, sonographic controls of the liver resection site are necessary, as well as controls to rule out a recurrence of a hemangioma.

Possible growth factors conducive to the development or growth of a hepatic hemangioma include (with some caveats) the use of oral contraceptives, or pregnancy. However, how these factors may influence hemangioma growth is not well understood. Similar to how hormones can promote the growth of benign liver tumors, it can be assumed that hormones also influence the growth of hemangiomas. Therefore, taking contraceptives in the case of a large hemangioma should be discussed with the gynecologist. A giant hemangioma of the liver must be monitored closely (e.g., with ultrasound) during pregnancy.

Patients can otherwise lead a completely normal life after hemangioma enucleation.